When you think of the word “model,” what do you think?

As an Economics major,

the first thing that comes to my mind is a statistical model, modeling phenomena such as the effect of class size on student test scores. A

car connoisseur’s mind might go straight to a model of their favorite vintage Aston

Martin. Someone else studying fashion even might imagine a runway model. The point is, the term “model” is used in popular discourse incredibly frequently, but are we even sure what it implies?

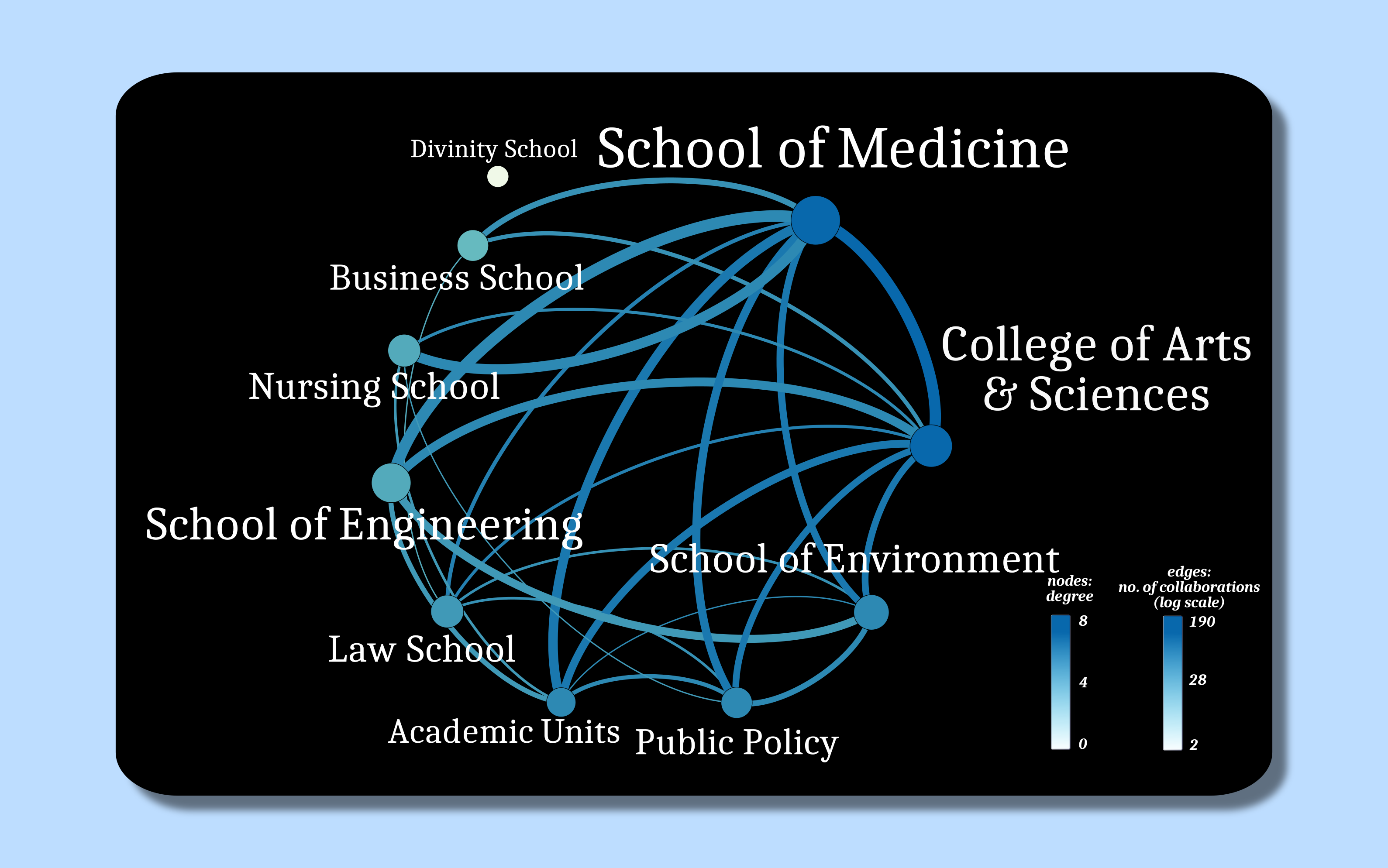

Annabel Wharton, a professor of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies at Duke, gave a talk entitled “Defining Models” at the Visualization Friday Forum. The forum is a place “for faculty, staff and students from across the university (and beyond Duke) to share their research involving the development and/or application of visualization methodologies.” Wharton’s goal was to answer the complex question, “what is a model?”

Annabel Wharton, a professor of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies at Duke, gave a talk entitled “Defining Models” at the Visualization Friday Forum. The forum is a place “for faculty, staff and students from across the university (and beyond Duke) to share their research involving the development and/or application of visualization methodologies.” Wharton’s goal was to answer the complex question, “what is a model?”

Wharton began the talk by defining the term “model,” knowing that it can often times be rather ambiguous. She stated the observation that models are “a prolific class of things,” from architectural models, to video game models, to runway models. Some of these types of things seem unrelated, but Wharton, throughout her talk, pointed out the similarities between them and ultimately tied them together as all being models.

The word “model” itself has become a heavily loaded term. According to Wharton, the dictionary definition of “model” is 9 columns of text in length. Wharton then stressed that a model “is an autonomous agent.” This implies that models must be independent of the world and from theory, as well as being independent of their makers and consumers. For example, architecture, after it is built, becomes independent of its architect.

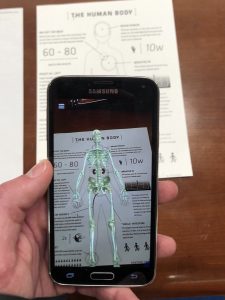

Next, Wharton outlined different ways to model. They include modeling iconically, in which the model resembles the actual thing, such as how the video game Assassins Creed models historical architecture. Another way to model is indexically, in which parts of the model are always ordered the same, such as the order of utensils at a traditional place setting. The final way to model is symbolically, in which a model symbolizes the mechanism of what it is modeling, such as in a mathematical equation.

Wharton then discussed the difference between a “strong model” and a “weak model.” A strong model is defined as a model that determines its weak object, such as an architect’s model or a runway model. On the other hand, a “weak model” is a copy that is always less than its archetype, such as a toy car. These different classifications include examples we are all likely aware of, but weren’t able to explicitly classify or differentiate until now.

Wharton finally transitioned to discussing one of her favorite models of all time, a model of the Istanbul Hagia Sophia, a former Greek Orthodox Christian Church and later imperial mosque.(See Also: https://muze.gen.tr/muze-detay/ayasofya)

Wharton finally transitioned to discussing one of her favorite models of all time, a model of the Istanbul Hagia Sophia, a former Greek Orthodox Christian Church and later imperial mosque.(See Also: https://muze.gen.tr/muze-detay/ayasofya)

She detailed how the model that provides the best sense of the building without being there is found in a surprising place, an Assassin’s Creed video game. This model is not only very much resembles the actual Hagia Sophia, but is also an experiential and immersive model. Wharton joked that even better, the model allows explorers to avoid tourists, unlike in the actual Hagia Sophia.

Wharton described why the Assassin’s Creed model is a highly effective agent. Not only does the model closely resemble the actual architecture, but it also engages history by being surrounded by a historical fiction plot. Further, Wharton mentioned how the perceived freedom of the game is illusory, because the course of the game actually limits players’ autonomy with code and algorithms.

After Wharton’s talk, it’s clear that models are definitely “a prolific class of things.” My big takeaway is that so many thing in our everyday lives are models, even if we don’t classify them as such. Duke’s East Campus is a model of the University of Virginia’s campus, subtraction is a model of the loss of an entity, and an academic class is a model of an actual phenomenon in the world. Leaving my first Friday Visualization Forum, I am even more positive that models are powerful, and stretch so far beyond the statistical models in my Economics classes.

By Nina Cervantes

Simple, right? Multiply that by 500,000 users worldwide, though, and it’s easy to see why researchers like Loarie are excited by the possibilities an app like this can offer. The software first went live in 2008, and since then its user base has roughly doubled each year. This has meant the generation of over 8 million data points of 150,000 different species, including one-third of all known vertebrate species and 40% of all known species of mammal. Every day, the app catalogues around 15 new species.

Simple, right? Multiply that by 500,000 users worldwide, though, and it’s easy to see why researchers like Loarie are excited by the possibilities an app like this can offer. The software first went live in 2008, and since then its user base has roughly doubled each year. This has meant the generation of over 8 million data points of 150,000 different species, including one-third of all known vertebrate species and 40% of all known species of mammal. Every day, the app catalogues around 15 new species. It’s this kind of interconnectivity that demonstrates not just the potential of apps like iNaturalist, but also the power of collaboration and the possibilities symposia like Duke Blueprint offer. Bridging gaps, tearing down boundaries, building up bonds—these are the heart of conservationism’s future. Nature and Progress, working together, pulling us forward into a brighter world.

It’s this kind of interconnectivity that demonstrates not just the potential of apps like iNaturalist, but also the power of collaboration and the possibilities symposia like Duke Blueprint offer. Bridging gaps, tearing down boundaries, building up bonds—these are the heart of conservationism’s future. Nature and Progress, working together, pulling us forward into a brighter world. Post by Daniel Egitto

Post by Daniel Egitto

Pictures from Duke Conservation Tech

Pictures from Duke Conservation Tech

Post by Thabit Pulak

Post by Thabit Pulak

Guest post by Eric Ferreri, News and Communications

Guest post by Eric Ferreri, News and Communications

Post by Stella Wang

Post by Stella Wang