Not all protein crystals exhibit the colorful iridescence of these crystals grown in space. But no matter their looks, all are important to scientists. Credit: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (NASA-MSFC).

Protein crystals don’t usually display the glitz and glam of gemstones. But no matter their looks, each and every one is precious to scientists.

Patrick Charbonneau, a professor of chemistry and physics at Duke, along with a worldwide group of scientists, teamed up with researchers at Google Brain to use state-of-the-art machine learning algorithms to spot these rare and valuable crystals. Their work could accelerate drug discovery by making it easier for researchers to map the structures of proteins.

“Every time you miss a protein crystal, because they are so rare, you risk missing on an important biomedical discovery,” Charbonneau said.

Knowing the structure of proteins is key to understanding their function and possibly designing drugs that work with their specific shapes. But the traditional approach to determining these structures, called X-ray crystallography, requires that proteins be crystallized.

Crystallizing proteins is hard — really hard. Unlike the simple atoms and molecules that make up common crystals like salt and sugar, these big, bulky molecules, which can contain tens of thousands of atoms each, struggle to arrange themselves into the ordered arrays that form the basis of crystals.

“What allows an object like a protein to self-assemble into something like a crystal is a bit like magic,” Charbonneau said.

Even after decades of practice, scientists have to rely in part on trial and error to obtain protein crystals. After isolating a protein, they mix it with hundreds of different types of liquid solutions, hoping to find the right recipe that coaxes them to crystallize. They then look at droplets of each mixture under a microscope, hoping to spot the smallest speck of a growing crystal.

“You have to manually say, there is a crystal there, there is none there, there is one there, and usually it is none, none, none,” Charbonneau said. “Not only is it expensive to pay people to do this, but also people fail. They get tired and they get sloppy, and it detracts from their other work.”

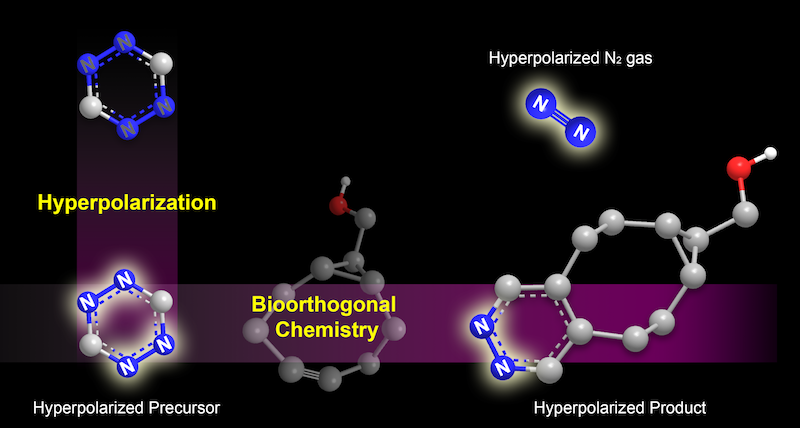

The machine learning software searches for points and edges (left) to identify crystals in images of droplets of solution. It can also identify when non-crystalline solids have formed (middle) and when no solids have formed (right).

Charbonneau thought perhaps deep learning software, which is now capable of recognizing individual faces in photographs even when they are blurry or caught from the side, should also be able to identify the points and edges that make up a crystal in solution.

Scientists from both academia and industry came together to collect half a million images of protein crystallization experiments into a database called MARCO. The data specify which of these protein cocktails led to crystallization, based on human evaluation.

The team then worked with a group led by Vincent Vanhoucke from Google Brain to apply the latest in artificial intelligence to help identify crystals in the images.

After “training” the deep learning software on a subset of the data, they unleashed it on the full database. The A.I. was able to accurately identify crystals about 95 percent of the time. Estimates show that humans spot crystals correctly only 85 percent of the time.

“And it does remarkably better than humans,” Charbonneau said. “We were a little surprised because most A.I. algorithms are made to recognize cats or dogs, not necessarily geometrical features like the edge of a crystal.”

Other teams of researchers have already asked to use the A.I. model and the MARCO dataset to train their own machine learning algorithms to recognize crystals in protein crystallization experiments, Charbonneau said. These advances should allow researchers to focus more time on biomedical discoveries instead of squinting at samples.

Charbonneau plans to use the data to understand how exactly proteins self-assemble into crystals, so that researchers rely less on chance to get this “magic” to happen.

“We are trying to use this data to see if we can get more insight into the physical chemistry of self-assembly of proteins,” Charbonneau said.

CITATION: “Classification of crystallization outcomes using deep convolutional neural networks,” Andrew E. Bruno, et al. PLOS ONE, June 20, 2018. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198883

Post by Kara Manke

Post by Kara Manke

Post by Kara Manke