What if some of the most innovative academic contributions this year didn’t come from tenured professors but students still working toward their degrees? Though often treated as a novel or even surprising idea, student researchers are producing work that challenges these assumptions and pushes the boundaries of work within their fields. Their contributions are not limited to classroom assignments but have transformed into real academic research with tangible impacts.

Nowhere is this more evident than at Duke’s Bass Connections showcase, where student researchers present the results of their year-long interdisciplinary projects. This past month, student researchers across all disciplines gathered together in Penn Pavilion to share work spanning fields from space policy to criminal justice. The showcase revealed how students are not only contributing to research efforts but instead actively shaping its future. Attending the showcase offered me a firsthand look at the creativity, depth, and relevance of these projects. Each one I encountered revealed a unique blend of academic rigor and public purpose that deserves to be highlighted:

Future Space Settlements: Lessons from History

One of the standout projects that I encountered was “Future Space Settlements: Lessons from History.” During the showcase, I had the pleasure of speaking to Simran Pandey (‘27), Lawrence Wu (‘27), and Nikhil Methi (‘27), who were part of the Future Space Settlements team. Their work explored how the legal, political, economic, and social histories of terrestrial colonization might inform future efforts to establish human settlements beyond Earth. Grounded in a policy-oriented framework, the team drew on historical case studies to both model and caution against potential approaches to space expansion

Group from L to R: Lawrence Wu, Simran Pandey, and Nikhil Methi

Over the summer, the team conducted extensive archival research and created a comprehensive database of treaties, documents, and records to anchor their analysis. Throughout the academic year, subteams focused on space settlements from different angles, including legal precedents, historical analogies, and speculative design. Additionally, the team met with experts within the fields of space and policy.

This level of coordination did not come without challenges. The researchers explained how, despite their ambitious scope, finding sources that bridged centuries of terrestrial history with their respective disciplines proved to be difficult. Pandey, Wu, and Methi explained how managing multiple disciplines in conjunction with a scarcity of sources made it difficult to produce a cohesive output. Reflecting on the experience, the team emphasized the importance of narrowing the project scope and aligning deliverables with capacity. As Methi noted, they “began with lofty ambitions,” but future years would benefit from a tighter focus to ensure depth over breadth.

Crisis Pregnancy Centers Post Roe v. Wade: Correlates of State Variation in Anti-Abortion Fake Clinics

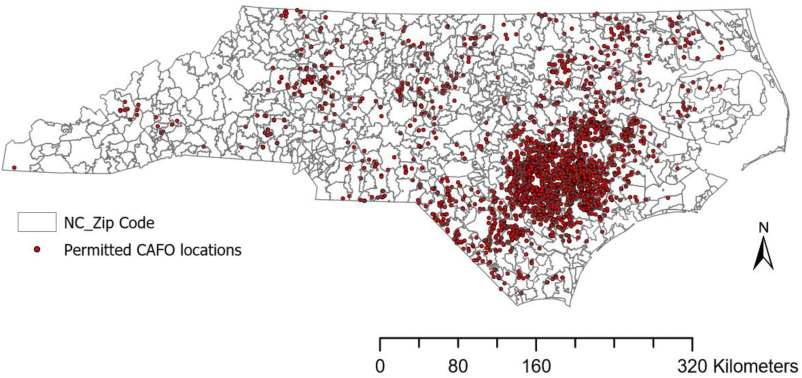

Another compelling project I learned about during the showcase was Crisis Pregnancy Centers Post Roe v. Wade: Correlates of State Variation in Anti-Abortion Fake Clinics. For this, I spoke to Anushri Saxena (‘25), who based her thesis on this research. Saxena explained how while on the team, she examined the rise and distribution of crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs) across the United States. CPCs are anti abortion organizations that often present themselves as legitimate abortion providers, intending to dissuade people from seeking abortion care. While they exist in all 50 states, the group’s research aimed to understand why some states host significantly more CPC’s per capita than others.

Anushri Saxena at the Bass Connections Showcase

To do this, Saxena personally used regression modeling by conducting a quantitative analysis of state-level policy. She used demographic factors such as Republican alignment, proportion of evangelical populations, and the restrictiveness of state abortion laws to identify key drivers of CPC density. The process involved conducting a literature review to identify relevant variables, building hypotheses, and learning statistical methods to execute her analysis.

One major challenge Saxena described was the volatile nature of reproductive healthcare policy, as significant legal shifts occurred even during the course of her writing. While reflecting on the limitations of state-level data, she expanded her work this semester to produce a more granular analysis of North Carolina, exploring how CPC’s are concentrated in census tracts marked by education levels, higher poverty rates, and more single-parent households. Her work provides not only a broader understanding of antiabortion mobilization but also a need for local community-specific policy responses in a post-Roe America.

Mental Health and the Justice System in Durham County

“Mental Health and the Justice System in Durham County” also stood out to me during this showcase. From this team, I was able to speak to Miranda Li (‘27) and Jacqueline Dinh (‘27). This project aimed to examine the intersection between incarceration and mental health outcomes, with a specific focus on Durham County.

From L to R: Miranda Li, and Jacqueline Dinh

To tackle these complexities, the team was divided into four sub-projects: two quantitative and two qualitative. On the quantitative side, one team explored how sociodemographic and spatial data influenced an individual’s likelihood of being rebooked, while another team worked to validate and analyze newly acquired jail service data, such as psychiatric visits and mental health interventions. On the qualitative side, one group led focused group-based interviews with formerly incarcerated individuals to assess whether existing jail services were effective in promoting recovery. Another subteam focused more on the experiences of family members of incarcerated individuals, highlighting the emotional burden that they carry and the importance of community support networks.

While Dinh and Li reflected on the freedom to shape their own qualitative approach, they also described the difficulty of managing an overwhelming influx of raw data and the importance of starting from ground zero to ensure validity. One of the biggest challenges that they struggled with as a group was a wide-open research structure. Although the autonomy was truly empowering, it sometimes led to uncertainty about direction and deliverables. Looking ahead, both researchers emphasized the value of continued collaboration with community stakeholders to better align the research with local needs and strengthen the actionable outcomes.

Together, these three projects spanning space policy, reproductive rights, and criminal justice highlight the depth of student-led research today. Each project showed not only academic rigor but also a clear commitment to addressing real-world issues through thoughtful, interdisciplinary inquiry. Their contributions serve as a powerful reminder that meaningful research is not solely limited to faculty but can also be a space where students lead with curiosity, creativity, and purpose.

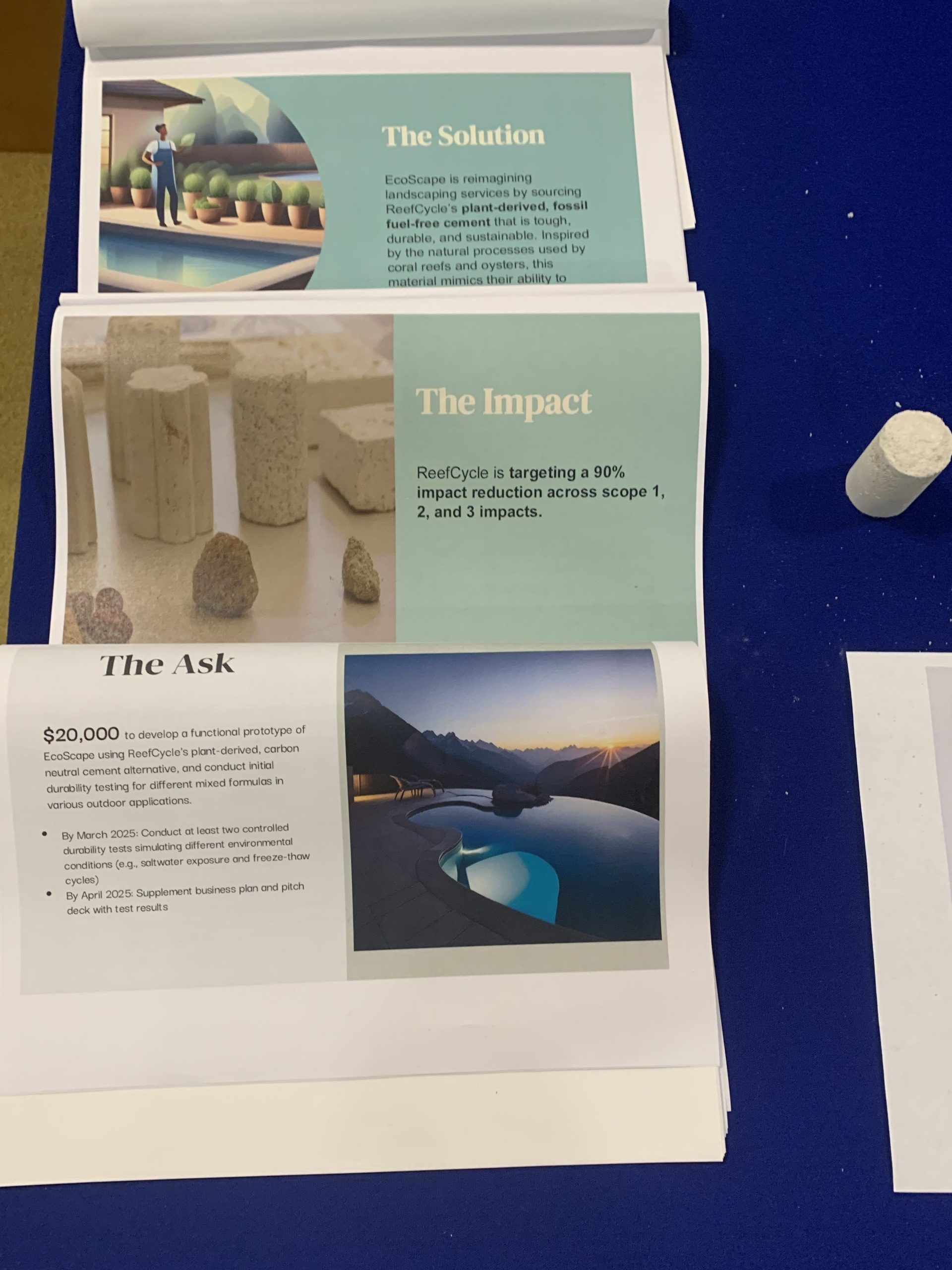

based and enzymatic, meaning it’s essentially grown using enzymes from beans. Testing in the New York Harbor yielded some promise: the cement appeared to resist corrosion, while becoming home for some oysters. The Design Climate team is now trying to bring it to more widespread use on land, while targeting up to a 90% reduction in carbon emissions

based and enzymatic, meaning it’s essentially grown using enzymes from beans. Testing in the New York Harbor yielded some promise: the cement appeared to resist corrosion, while becoming home for some oysters. The Design Climate team is now trying to bring it to more widespread use on land, while targeting up to a 90% reduction in carbon emissions