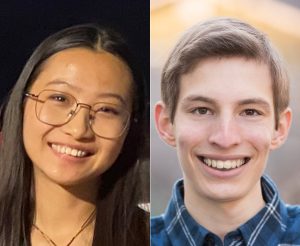

Bandaids and pimple patches are the first things we consider when discussing adhesives in medicine. But what if there is more to the story? What if adhesives could not only cover and protect but also diagnose and communicate? It turns out Dr. Wei Gao, assistant professor of medical engineering at the California Institute of Technology, is asking these exact questions. In the field of biomedical adhesives, Gao’s research is revolutionizing our understanding of precision medicine and medical testing accessibility. He visited Duke on Oct. 9 to present his work as part of the MEMS (Mechanical Engineering and Material Science) Seminar Series.

Gao’s research team focuses on material, device, and system innovations that apply molecular research and principles to clinical settings and improve health. Gao focused his talk on the invaluable characteristics and uses of sweat. Sweat can offer doctors a broad spectrum of information, including nutrients, biomarkers, pH levels, electrolytes/salts, and hormones. He leverages this fundamental characteristic of human physiology to design wearable biosensors that can provide early warnings of health issues or diseases. Gao focuses on making biomarker detection more efficient than current methods, such as blood samples, which require hospital testing, involve highly invasive techniques, and lack continuous monitoring.

The first milestone in his research came in 2016 when he introduced a fully printed, wearable, real-time monitoring sensor device. The device allowed them to continuously collect sweat and wirelessly communicate data about these sweat samples from patients onto digital devices. The initial 2016 device focused on resolving four fundamental challenges: since most chemical sensors are not stable over long periods of time, the device had to be (1) low-cost and (2) disposable without sacrificing performance. In addition, the device had to (3) be mass-producible to be accessible to the public and (4) integrate multiple signals that could be real-time transmitted to a digital interface.

To address the first two of those challenges, Gao and his group turned to printing techniques. The circuit substrate was a thin piece of flexible PET (a plastic), upon which they layered the circuit components. The flexible sensor array was constructed in a similar pattern, with a layer of PET patterned with gold to produce the electrodes, covered with parylene, and then each electrode was tuned to receive a specific chemical stimulus: potassium and sodium ion sensors, with a polyvinyl butyrate reference electrode, and oxidase-based glucose and lactate sensors paired with a silver/silver chloride reference electrode. This design allows the simultaneous monitoring of multiple biomarkers. To transmit the data wirelessly, the circuit board included a Bluetooth transceiver.

The next major step was to devise a way to monitor sweat without relying upon heat or vigorous exercise, neither of which may be feasible in the case of clinically ill patients. In a 2023 paper, Gao and colleagues published a biosensor that could induce localized sweating using an electric circuit. Called iontophoresis, the technique delivers a drug (a cholinergic agonist) that stimulates the sweat glands on demand and only in the area of the sensor.

Another important question was how to power the devices sustainably. Gao’s lab has devised two primary responses to this question: In a 2020 paper, his team powered a similar multiplexed wireless sensor entirely using electricity generated from compounds in sweat. This entailed using lactate biofuel cells to harness the oxidation of lactate to pyruvate (coupled with the reduction of oxygen to water) to provide a stable current. In a 2023 paper, they employed a flexible perovskite solar cell onboard the device to power the monitoring of a suite of biomarkers.

With these technical hurdles overcome, Gao and his lab have been able to develop sensors targeted to several important medical applications. The work can be directly applied to the monitoring of conditions like cystic fibrosis and gout. More broadly, wearable biosensors can be used to track levels of medically relevant compounds like cortisol (for stress monitoring), C reactive protein (inflammation), and reproductive hormones. The lab has also branched into other kinds of devices that use similar microfluidics approaches, including smart bandages for wound monitoring and smart masks to detect biomarkers in breath.

Through eight years of dedicated investigation, Gao serves as a pioneer in the field of bioelectronic interfaces. Gao continues to widen the possibilities of biosensors not only within the medical sphere but also for the general public. For example, his lab is collaborating with NASA and the U.S. Navy to support the performance and health of astronauts and our military, which is vital as they work in extreme environments. By pushing forward ground-breaking devices such as sweat biosensors, our healthcare systems can pursue preventative care, reducing the need for treatments or health resources by catching these issues early on. Following Gao’s footsteps, we can now build toward a healthier future as we improve the precision of our healthcare approaches and technological advancements.