Imagine having an app that could identify almost anyone using only a photograph of their face. For example, you could take a photograph of a stranger in a dimly lit restaurant and know within seconds who they are.

This technology exists, and Kashmir Hill has reported on several companies that offer these services.

An investigative journalist with the New York Times, Hill visited Duke Law Sept. 27 to talk about her new book, Your Face Belongs To Us.

The book is about a company that developed powerful facial recognition technology based on images harnessed from our social media profiles. To learn more about Clearview AI, the unlikely duo who were behind it, and how they sold it to law enforcement, I highly recommend reading this book.

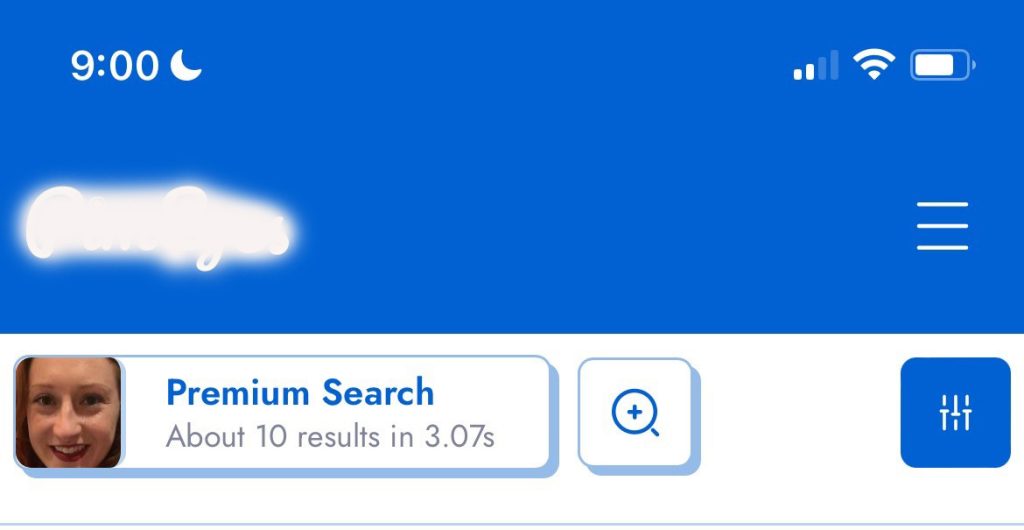

Hill demonstrated for me a facial recognition app that provides subscribers with up to 25 face searches a day. She offered to let me see how well it worked.

She snapped a quick photo of my face in dim lighting. Within seconds (3.07 to be exact), several photos of my face appeared on her phone.

The first result (top left) is unsurprising. It’s the headshot I use for the articles I write on the Duke Research Blog. The second result (top right) is a photo of me at my alma mater in 2017, where I presented at a research conference. The school published an article about the event, and I remember the photographer coming around to take photos. I was able to easily figure out exactly where on the internet both results had been pulled from.

The third result (second row, left) unsettled me. I had never seen this photo before.

After a quick search of the watermark on the photo (which has been blurred for safety), I discovered that the photograph was from an event I attended several years ago. Apparently, the venue had used the image for marketing on their website. Using these facial recognition results, I was able to easily find out the exact location of the event, its date, and who I had gone with.

What is Facial Recognition Technology?

Researchers have been trying for decades to produce a technology that could accurately identify human faces. The invention of neural network artificial intelligence has made it possible for computer algorithms to do this with increasing accuracy and speed. However, this technology requires large sets of data, in this case, hundreds of thousands of examples of human faces, to work.

Just think about how many photos of you exist online. There are the photos that you have taken and shared or that your friends and family have taken of you. Then there are photos that you’re unaware that you’re in – perhaps you walked by as someone snapped a picture and accidentally ended up in the frame. I don’t consider myself a heavy user of social media, but I am sure there are thousands of pictures of my face out there. I’ve uploaded and classified hundreds of photos of myself across platforms like Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and even Venmo.

The developers behind Clearview AI recognized the potential in all these publicly accessible photographs and compiled them to create a massive training dataset for their facial recognition AI. They did this by scraping the social media profiles of hundreds of thousands of people. In fact, they got something like 2.1 million images of faces from Venmo and Tinder (a dating app) alone.

Why does this matter?

Clearly, there are major privacy concerns for this kind of technology. Clearview AI was marketed as being only available to law enforcement. In her book, Hill gives several examples of why this is problematic. People have been wrongfully accused, arrested, detained, and even jailed for the crime of looking (to this technology) like someone else.

We also know that AI has problems with bias. Facial recognition technology was first developed by mostly white, mostly male researchers, using photographs of mostly white, mostly male faces. The result of this has had a lasting effect. Marginalized communities targeted by policing are at increased risk, leading many to call for limits on the use of facial recognition by police.

It’s not just government agencies who have access to facial recognition. Other companies have developed off-the-shelf products that anyone can buy, like the app Hill demonstrated to me. This technology is now available to anyone willing to pay for a subscription. My own facial recognition results show how easy it is to find out a lot about a person (like their location, acquaintances, and more) using these apps. It’s easy to imagine how this could be dangerous.

There remain reasons to be optimistic about the future of privacy, however. Hill closed her talk by reminding everyone that with every technological breakthrough, there is opportunity for ethical advancement reflected by public policy. With facial recognition, policy makers have previously relied on private companies to make socially responsible decisions. As we face the results of a few radical actors using the technology maliciously, we can (and should) respond by developing legal restraints that safeguard our privacy.

On this front, Europe is leading by example. It’s likely that the actions of Clearview AI are already illegal in Europe, and they are expanding privacy rights with the European Commission’s (EC) proposed Artificial Intelligence (AI) regulation. These rules include requirements for technology developers to certify the quality of their processes, rather than algorithm performance, which would mitigate some of these harms. This regulation aims to take a technology-neutral approach and stratifies facial recognition technology by it’s potential for risk to people’s safety, livelihoods, and rights.

Post by Victoria Wilson, MA Bioethics and Science Policy, 2023

By Victoria Wilson, Class of 2023

By Victoria Wilson, Class of 2023