It all starts with a simple question: How can I help? For some Duke students, the answer meant taking initiative – transforming empathy into action, ideas, and impact in order to tackle the most pressing global health issues head-on.

On April 10, 2025, two Duke teams were among 22 semi-finalist teams, representing 18 universities across eight countries, who met at the 15th Annual Global Health Technologies Design Competition on the Rice University campus. There, the students exchanged their strong passions about global health and learned from one another’s efforts to address the needs of low-resource communities. The projects spanned a wide spectrum of challenges, from portable glaucoma detection devices for applications in rural Peru, to low-cost sensor-based gloves for translating sign language into voice in real time, and many more!

The competition was hosted by the Rice360 Institute for Global Health Technologies, a multi-disciplinary institute that aims to elevate global health technology education and research. Following their mission, this event helped to raise awareness about students who are leading global health innovation. Moreover, participating students received the opportunity to engage with judges, mentors, and interested attendees with expertise in global health for vital feedback and recommendations for future project plans.

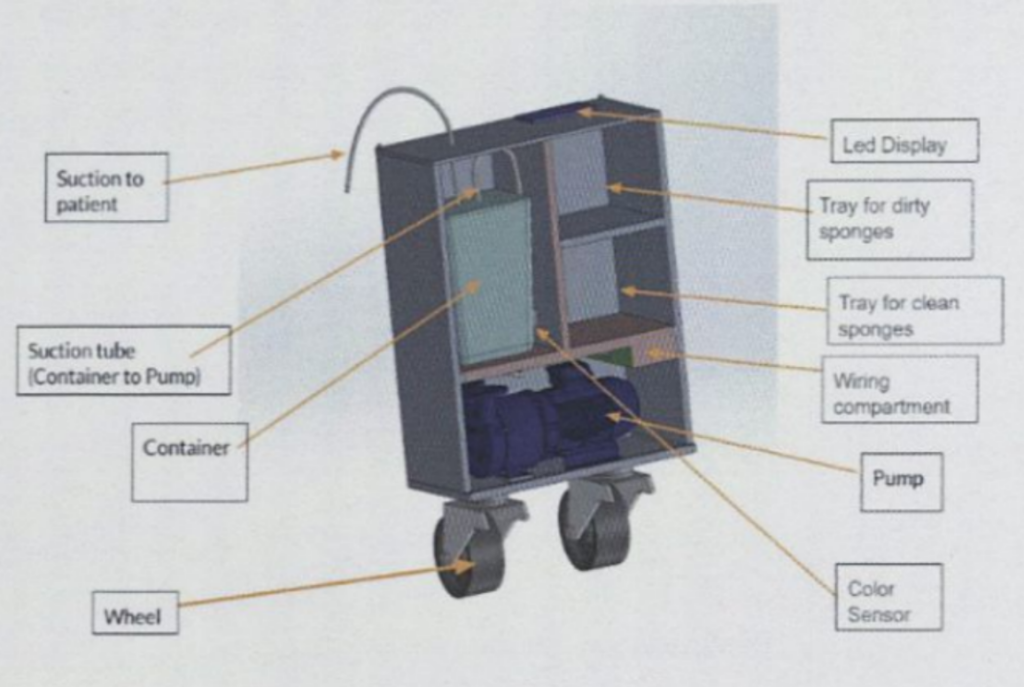

The two Duke teams that qualified as semi-finalists were HemoSave and VenAlign. HemoSave was awarded first place for their project targeting the leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide, an excessive loss of blood after childbirth called postpartum hemorrhage. To combat this critical issue, the HemoSave team designed a cost-effective blood loss tracking device that uses colorimetric and gravimetric analysis. By doing so, the device allows clinicians to accurately measure blood loss during C-sections to improve high-stakes decision-making in low-resource settings. All components of the design were locally sourced from Kampala, Uganda, to maximize affordability and accessibility within such low-resource settings.

Second place was awarded to QBiT A.R.M. from Queen’s University for their work on developing low-cost, 3-D printable arm prosthetics. Their open-source design allows “clinics in lower- and middle-income countries to produce prosthetics on-site, restoring mobility and independence for those in need” (Rice360).

BiliRoo from Calvin University won third place for their device that combines filtered sunlight phototherapy technology and skin-to-skin contact between parent and child to treat neonatal jaundice in low-resource settings. For more information and to learn about the rest of the other incredible projects, please refer to the Rice360 website (link).

In addition to the student competition, Rice360 honored two current leaders in Global Health this year for their continued perseverance and successes within innovation for Global Health. The two recipients for the Rice360 Innovation and Leadership in Global Health Award were Dr. June Madete and Dr. Patty J. García, both successful leaders of global health in their own right.

After noticing a disheartening lack of biomedical engineering in Kenya, Madete realized the necessity of applying her scientific experience to advancing biomedical adoption within sub-Saharan Africa. She is now a senior lecturer and researcher at Kenyatta University, where she leads education efforts in engineering to connect with students, lecturers, scientists, and industry all across Africa.

García has also dedicated her career to advancing global health, but through a more public policy perspective. As the former Minister of Health in Peru and former Chief of the Peruvian National Institute of Health, García worked to translate critical biomedical research into real-world applications across Peru and Latin America. Her work to improve research on and the quality of health services surrounding reproductive health and sexually transmitted infections has worked to improve the safety and well-being of critical communities and vulnerable populations.

As the keynote speakers, Madete and García shared their distinct journeys across opposite sides of the globe, each grounded in a common goal to advance the well-being of underserved communities through global health innovation and education. Altogether, the students, speakers, and supporters at this year’s Rice360 competition demonstrated that meaningful change is already in motion, driven by hope for a healthier, more equitable world.

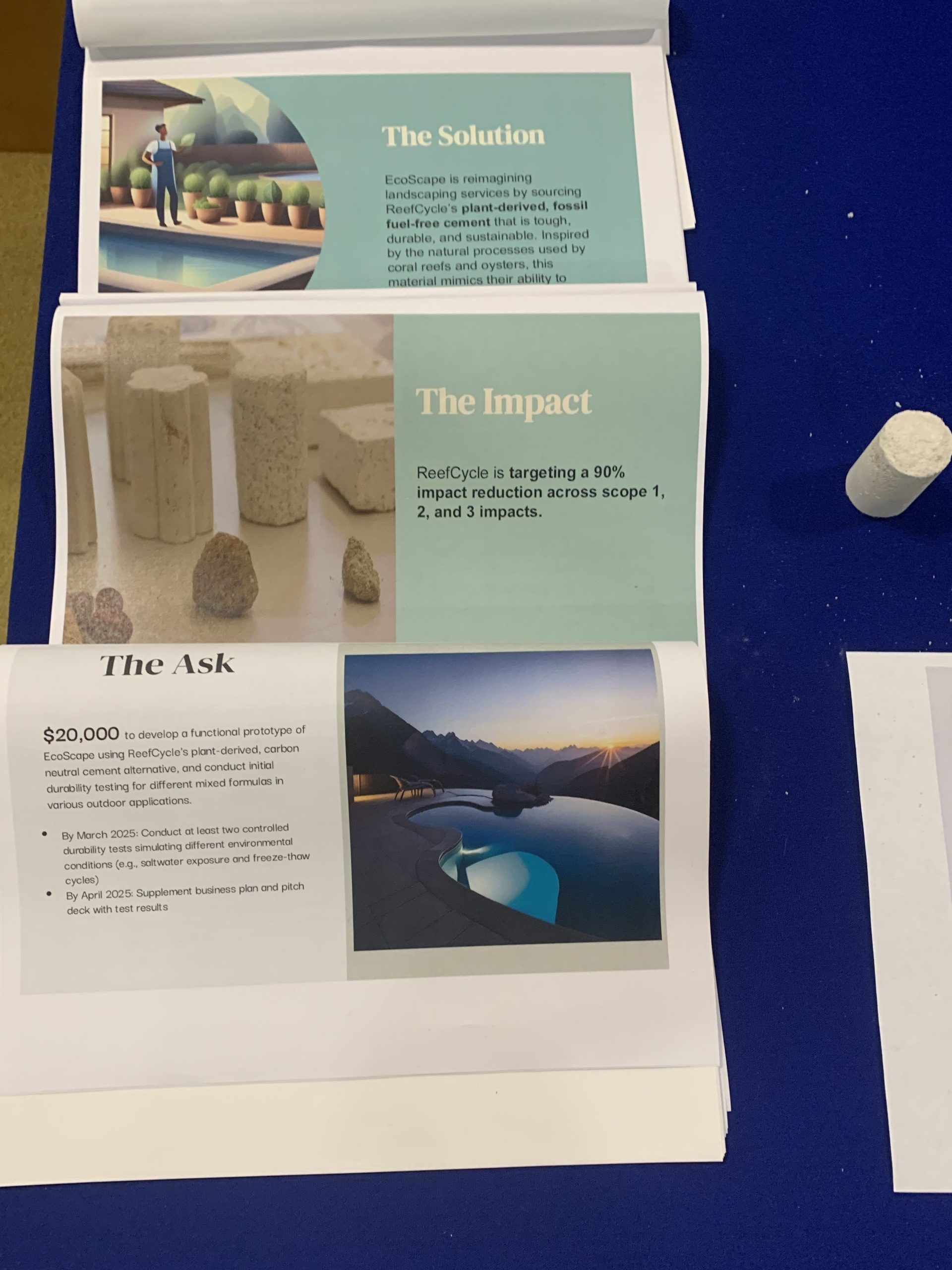

based and enzymatic, meaning it’s essentially grown using enzymes from beans. Testing in the New York Harbor yielded some promise: the cement appeared to resist corrosion, while becoming home for some oysters. The Design Climate team is now trying to bring it to more widespread use on land, while targeting up to a 90% reduction in carbon emissions

based and enzymatic, meaning it’s essentially grown using enzymes from beans. Testing in the New York Harbor yielded some promise: the cement appeared to resist corrosion, while becoming home for some oysters. The Design Climate team is now trying to bring it to more widespread use on land, while targeting up to a 90% reduction in carbon emissions