COVID-19 continues to plague us, Mpox is an emerging global threat, and the avian flu is decimating industrial poultry as well as endangered wildlife. What do all these epidemics have in common? They originated in wild animals and spread to domestic animals and people.

This pattern of spread is a trademark of many diseases, termed zoonoses or zoonotic diseases. Our new research shows that in rural settings of Madagascar where forested landscapes were converted to agriculture and settlements, the potential transmission of a deadly virus, Hantavirus, is likely facilitated by invasive rodents, especially the black rat. Also responsible for cyclically occurring plague events in Madagascar, the black rats could be transmitting multiple diseases to people in rural communities, based on our studies.

The work was published April 7 in the journal Ecology and Evolution.

Hantavirus is mainly spread from rodents to people via exposure to their urine and feces in the environment, and being bitten. It can cause severe and deadly disease of the lungs and kidneys, resulting in fever, fatigue, aches and pains, followed later by coughing, shortness of breath, and fluid in the lungs, causing death in almost 40% of people who experience later-stage symptoms. In rural settings like in Madagascar, there are no tests available to diagnose Hantavirus, and the generalized symptoms are often confused for influenza or other diseases. With no specific treatment, either, Hantavirus is an important, though neglected, zoonotic pathogen.

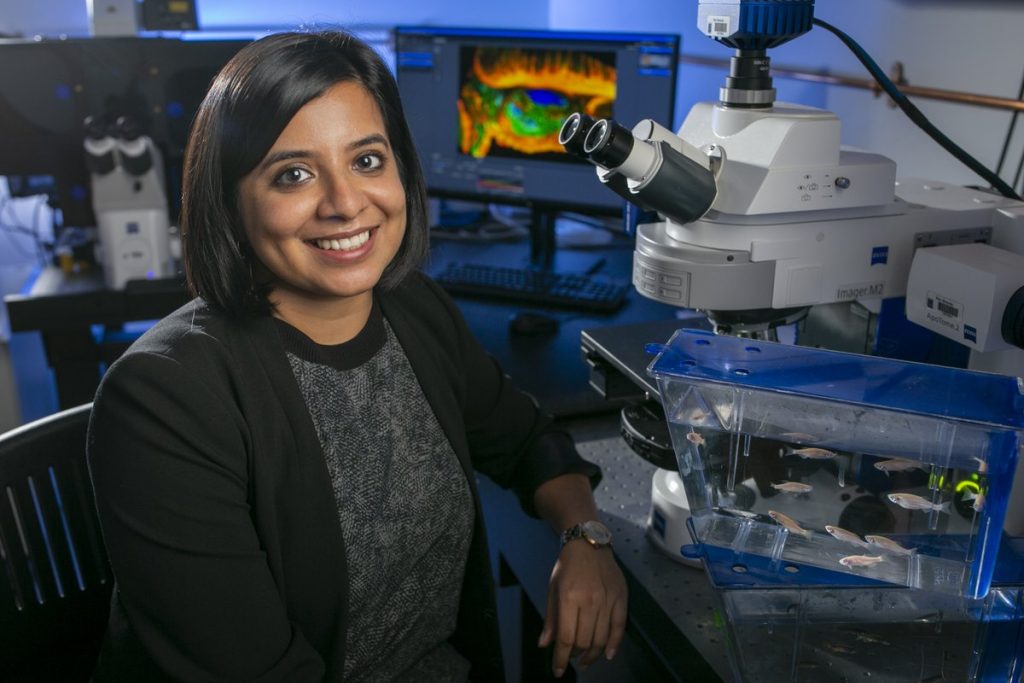

This research, funded by the U.S. National Institute of Health and National Science Foundation, as well as Duke University, connects scientists from around the world with diverse specialties, including field biology, infectious disease epidemiology, social sciences, veterinary health, and more. Over the last eight years, our international and interdisciplinary team studied zoonotic pathogens in wildlife, domestic animals, and people. We compare how pathogens vary among different animals and in different landscapes.

There are more than 29 species of small mammals and another 12 species of bats in these wildlife communities, including native rodents and animals that look like hedgehogs and shrews but are a unique group from Madagascar, the tenrecs. There are also ubiquitous introduced mammals, including black rats, the house mouse, and the shrew, which have spread around the world wherever almost everywhere people go. We studied natural, pristine rainforests and compared to different features of the agroecosystem including regenerating forests, agroforests, and rice fields. We captured rodents and shrews in people’s households, as well, to compare how small mammals and zoonotic pathogens change over this gradient of human land use.

Our results show that black rats were the only species in our system that were infected with Hantavirus, with 10% of sampled individuals infected. Rat abundance and infection were higher in agricultural settings, including rice fields and agroforests, where rats were larger. While some rats in people’s homes were infected, no infected individuals were found in the more mature forests. Hantavirus infection was lower in the homes than in the agricultural fields, but exposure to infected rats is likely higher in homes because of the close contact in enclosed settings. The results highlight how infectious disease risk varies across the landscape because of complex impacts of human land use on natural ecosystems.

The Hantavirus results closely mirror those our team have shown for other disease-causing emerging pathogens, including Astroviruses and Leptospira. Rats and the house mouse were the most commonly infected species, and in the case of Astrovirus, only a single individual of a native species was infected. While Astrovirus infection was more common in the regenerating scrubby environments, Leptospira infection was most common in seasonally flooded rice fields. These varying landscapes of disease risk have important implications for the emergence of zoonotic diseases as well as applications to policy for public health.

Preserving natural forest and facilitating the regeneration of transformed forests may decrease disease risk because infected individuals were rarely captured in natural forests. This may be because there are natural predators to keep rodent populations in check, though further research is needed. Calls to eradicate black rat populations have seldom been successful, but through nature-based solutions like restoration to encourage natural predators, it may be possible to decrease abundance of nuisance rodents. Awareness-raising campaigns to teach about the signs and symptoms of common rodent-borne diseases for rural communities will also be rolled out, and encouraging local health care workers to check for these symptoms in the community members they serve.

We share our results with the Ministry of Public Health and Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, and will be organizing more think-tank meetings with relevant actors to co-design intervention strategies that can address these potentially emerging threats to human well-being.