How can we even begin to understand the human brain? Can we predict the way people will respond to stress by looking at their brains? Is it possible, even, to predict depression based on observations of the brain?

These answers will have to come from sets of data, too big for human minds to work with on our own. We need mechanical minds for this task.

Machine learning algorithms can analyze this data much faster than a human could, finding patterns in the data that could take a team of researchers far longer to discover. It’s just like how we can travel so much faster by car or by plane than we could ever walk without the help of technology.

David Carlson in his Duke office.

I had the opportunity to speak to David Carlson, an assistant professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering with a dual appointment at the Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics at Duke University. Through machine learning algorithms, Carlson is connecting researchers across campus, from doctors to statisticians to engineers, creating a truly interdisciplinary research environment around these tools.

Carlson specializes in explainable machine learning: algorithms with inner workings comprehensible by humans. Most deep machine learning today exists in a “black box” — the decisions made by the algorithm are hidden behind layers of reasoning that give it incredible predictive power but make it hard for researchers to understand the “why” and the “how” behind the results. The transparent algorithms used by Carlson offer a way to capture some of the predictive power of machine learning without sacrificing our understanding of what they’re doing.

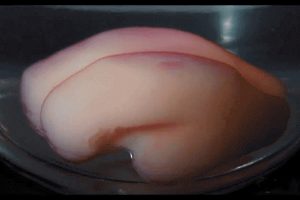

In his most recent research, Carlson collaborated with Dr. Kafui Dzirasa, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and assistant professor in neurobiology and neurosurgery, on the effects of stress on the brains of mice, trying to understand the underlying causes of depression.

“What’s happening in neuroscience is the amount of data we’re sorting through is growing rapidly, and it’s really beginning to outstrip our ability to use classical tools,” Carlson says. “A lot of these classical tools made a lot more sense when you had these small data sets, but now we’re talking about this canonically overused word, Big Data”

With machine learning algorithms, it’s easier than ever to find trends in these huge sets of data. In his most recent study, Carlson and his fellow researchers could find patterns tied to stress and even to how susceptible a mouse was to depression. By continuing this project and looking at new ways to investigate the brain and check their results, Carlson hopes to help improve treatments for depression in the future.

In addition to his ongoing research into depression, Carlson has brought machine learning to a number of other collaborations with the medical center, including research into autism and patient care for diabetes. When there’s too much data for the old ways of data analysis, machine learning can step in, and Carlson sees potential in harnessing this growing technology to improve health and care in the medical field.

“What’s incredibly exciting is the opportunities at the intersection of engineering and medicine,” he said. “I think there’s a lot of opportunities to combine what’s happening in the engineering school and also what’s happening at the medical center to try to create ways of better treating people and coming up with better ways for making people healthier.”

Guest Post by Thomas Yang, a junior at North Carolina School of Math and Science.

Guest Post by Thomas Yang, a junior at North Carolina School of Math and Science.

Guest Post by Isaac Poarch, a senior at the North Carolina School of Science and Math

Guest Post by Isaac Poarch, a senior at the North Carolina School of Science and Math

Guest Post by Sindhu Polavaram, a senior at North Carolina School of Science and Math

Guest Post by Sindhu Polavaram, a senior at North Carolina School of Science and Math

Guest Post by Sofia Sanchez, a senior at North Carolina School of Math and Science

Guest Post by Sofia Sanchez, a senior at North Carolina School of Math and Science

What is morphogenesis? Morphogenesis examines the development of the living organisms’ forms.

What is morphogenesis? Morphogenesis examines the development of the living organisms’ forms.  Can morphogenesis make sense of these differences? Through mathematical modeling, two stimuli for shoots’ shapes was determined: gravity and itself. Additionally, elasticity as a function of the shoots’ weight plays a role in the mathematical models of plant shoots’ shapes which appear in

Can morphogenesis make sense of these differences? Through mathematical modeling, two stimuli for shoots’ shapes was determined: gravity and itself. Additionally, elasticity as a function of the shoots’ weight plays a role in the mathematical models of plant shoots’ shapes which appear in

Dr. Zachary Zenko

Dr. Zachary Zenko Next, Dr. Zenko pointed out a common assumption in exercise psychology: if people know how good exercise is for them, they will exercise. However, this hasn’t proven to be true. Most people already know that they should be exercising, but don’t. And those that do often quickly drop out.

Next, Dr. Zenko pointed out a common assumption in exercise psychology: if people know how good exercise is for them, they will exercise. However, this hasn’t proven to be true. Most people already know that they should be exercising, but don’t. And those that do often quickly drop out. By Nina Cervantes

By Nina Cervantes

Post by Will Sheehan

Post by Will Sheehan