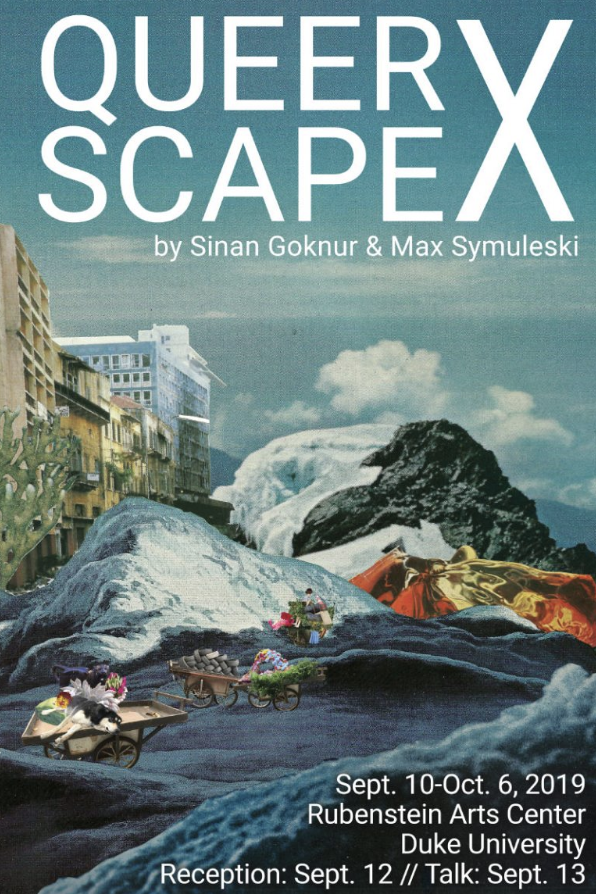

On September 10th, queerXscape, a new exhibit in The Murthy Agora Studio at the Rubenstein Arts Center, opened. Sinan Goknur and Max Symuleski, PhD candidates in the Computational Media, Arts & Cultures Program, created the installation with digital prints of collages, cardboard structures, videos, and audio. Max explains that this multi-media approach transforms the studio from a room into a landscape which provides an immersive experience.

The two artists combined their experiences with changing urban environments when planning this exhibit. Sinan reflects on his time in Turkey where he saw constant construction and destruction, resulting in a quickly shifting landscape. While processing all of this displacement, he began taking pictures as “a way of coping with the world.” These pictures later become layers in the collages he designed with Max.

Meanwhile, Max used their time in New York City where they had to move from neighborhood to neighborhood as gentrification raised prices. Approaching this project, they wondered, “What does queer mean in this changing landscape? What does it mean to queer something? Where are our spaces? Where do we need them to survive?” They had previously worked on smaller collages made from magazines that inspired the pair of artists to try larger-scale works.

Both Sinan and Max have watched the exploding growth in Durham while studying at Duke. From this perspective, they were able to tackle this project while living in a city that exemplifies the themes they explore in their work.

Using a video that Sinan had made as inspiration for the exhibit, they began assembling four large digital collages. To collaborate on the pieces, they would send the documents back and forth while making edits. When it became time to assemble their work, they had to print the collage in large strips and then careful glue them together. Through this process, they learned the importance of researching materials and experimented with the best way to smoothly place the strips together. While putting together mound-like cardboard structures of building, tire, and ice cube cut-outs, Max realized that, “we’re now doing construction.” Consulting with friends who do small construction and maintenance jobs for a living also helped them assemble and install the large-scale murals in the space. The installation process for them was yet another example of the tension between various drives for and scales of constructions taking place around them.

While collage and video may seem like an odd combination, they work together in this exhibit to surround the viewer and appeal to both the eyes and ears. Both artists share a background in queer performance and are driven to the rough aesthetics of photo collage and paper. The show brings together aspects of their experience in drag performance, collage, video, photography, and paper sculpture of a balanced collaboration. Their work demonstrates the value of partnership that crosses genres.

When concluding their discussion of changing spaces, Max mentioned that, “our sense of resilience is tied to the domains where we could be queer.” Finding an environment where you belong becomes even more difficult when your landscape resembles shifting sand. Max and Sinan give a glimpse into the many effects of gentrification, destruction, and growth within the urban context.

The exhibit will be open until October 6. If you want to see the results of weeks of collaging, printing, cutting, and pasting together photography accumulated from near and far, stop by the Ruby.

Post by Lydia Goff

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62603270/AP_18332234595077.0.jpg)

Post by Lydia Goff

Post by Lydia Goff

His biggest challenge is that the data he needs to analyze does not exist in a well-documented manner. Much of his research involves gathering data so that he can generate results. His published book,

His biggest challenge is that the data he needs to analyze does not exist in a well-documented manner. Much of his research involves gathering data so that he can generate results. His published book,