While some students like to spend their summer recovering from a long year of school work, others are working diligently in the Innovation Co-Lab in the Telcom building on West Campus.

They’re working on the impacts of dust and particulate matter (PM) pollution on solar panel performance, and discovering new technologies that map out the 3D volume of the ocean.

The Co-Lab is one of three 3D printing labs located on campus. It allows students and faculty the opportunity to creatively explore research through the use of new and emerging technologies.

Third-year PhD candidate Michael Valerino said his long term research project focuses on how dust and air pollution impacts the performance of solar panels.

“I’ve been designing a low-cost prototype which will monitor the impact of dust and air pollution on solar panels,” said Valerino. “The device is going to be used to monitor the impacts of dust and particulate matter (PM) pollution on solar panel performance. This processis known as soiling. This is going to be a low-cost alternative (~$200 ) to other monitoring options that are at least $5,000.”

Most of the 3D printers come with standard Polylactic acid (PLA) material for printing. However, because his first prototype completely melted in India’s heat, Valerino decided to switch to black carbon fiber and infused nylon.

“It really is a good fit for what I want to do,” he said. “These low-cost prototypes will be deployed in China, India, and the Arabian Peninsula to study global soiling impacts.”

In a step-by-step process, he applied acid-free glue to the base plate that holds the black carbon fiber and infused nylon. He then placed the glass plate into the printer and closely examined how the thick carbon fiber holds his project together.

Michael Bergin, a professor of civil and environmental engineering professor at Duke collaborated with the Indian Institute of Technology-Gandhinagar and the University of Wisconsin last summer to work on a study about soiling.

The study indicated that there was a decrease in solar energy as the panels became dirtier over time. The solar cells jumped 50 percent in efficiency after being cleaned for the first time in several weeks. Valerino’s device will be used to expand Bergin’s work.

As Valerino tackles his project, Duke student volunteers and high school interns are in another part of the Co-Lab developing technology to map the ocean floor.

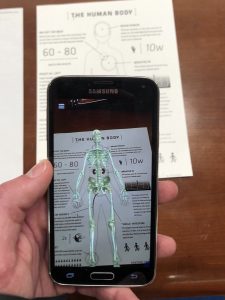

The Blue Devil Ocean Engineering team will be competing in the Shell Ocean Discovery XPRIZE, a global technology competition challenging teams to advance deep-sea technologies for autonomous, fast and high-resolution ocean exploration. (Their mentor, Martin Brooke, was recently featured on Science Friday.)

The team is developing large, highly redundant carbon drones that are eight feet across. The drones will fly over the ocean and drop pods into the water that will sink to collect sonar data.

Tyler Bletsch, a professor of the practice in electrical and computer engineering, is working alongside the team. He describes the team as having the most creative approach in the competition.

“We have many parts of this working, but this summer is really when it needs to come together,” Bletsch said. “Last year, we made it through round one of the competition and secured $100,000 for the university. We’re now using that money for the final phase of the competition.”

The final phase of the competition is scheduled to be held fall 2018.

Though campus is slow this summer, the Innovation Co-Lab is keeping busy. You can keep up-to-date with their latest projects here.

Post by Alexis Owens

Post by Alexis Owens

long repeating patterns of atoms in a chain — to thank for that. In fact, you can turn almost any liquid into a gel. Polymers take up little space but play a vital role in not only foods but other everyday objects, like contact lenses.

long repeating patterns of atoms in a chain — to thank for that. In fact, you can turn almost any liquid into a gel. Polymers take up little space but play a vital role in not only foods but other everyday objects, like contact lenses.

Guest post by Eric Ferreri, News and Communications

Guest post by Eric Ferreri, News and Communications