Recent studies have confirmed that exercising is just about the best thing you can do for your brain health.

Dan Blazer, MD is a psychiatrist who studies aging.

On Dec. 1 during the DIBS event, Exercise and the Brain, Duke psychiatrist Dan Blazer reported findings about the relationship between physical activity and brain health. After lots of research, study groups at the National Academy of Medicine concluded that their number one recommendation to those experiencing “cognitive aging” is exercise.

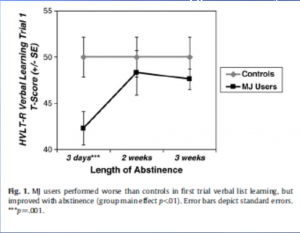

Processing speed, memory, and reasoning decline over time in every one of us. But thankfully, simple things like riding a bike or playing pick up basketball can help keep our minds fresh and at their best possible level.

One cool thing a committee conducting the research did to advertise their findings was create keychains saying “take your brain for a walk.” There’s a little image of a brain with legs walking. They wanted to get the word out that physical activity has another benefit than just staying in shape — it can also support your cognitive health.

However, the committees are having a hard time motivating people to exercise in the first place. Even after hearing their findings, it’s not like people everywhere are suddenly going to get off their couches and hit the gym. A world with healthier people — both physically and mentally — sounds nice, but getting there is much more than a matter of publishing these studies.

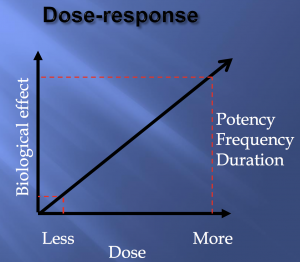

And, as always, too much of a good thing can make it harmful. While there does seem to appear a potential “biological gradient,” where greater physical activity correlated with better outcomes, you can’t just run a marathon every day of the week and then ~boom~ aging hardly affects your brain anymore. You don’t want to do that to yourself. Just get a healthy amount of exercise and you’ll be keeping your brain young and smart.

One of the best parts about why exercising is so great for you and your brain is because it helps you sleep (and we all know how important sleep is). If you ever have trouble going to bed or are having disrupted sleeps, physical activity could be your savior. It’s a much healthier option for your brain than taking stuff like melatonin, and you’ll get fit in the process.

Regarding exercising and Alzheimer’s, a disease where vital mental functions deteriorate, studies have unfortunately been insufficient to conclude anything. But if getting Alzheimer’s is your worst fear, I’m sure staying active can’t hurt as a preventative. More research on this topic is being conducted as we speak.

When is the best time to start exercising, in order to reap the maximum cognitive benefits, you ask? Well, the sooner the better. As Blazer said, “exercising helps in maintaining or improving cognitive function in later life,” so you better get on that. Go outside and get moving!

Post by Will Sheehan

Post by Will Sheehan

research between

research between

(

(

Post by Kara Manke

Post by Kara Manke

Post by Daniel Egitto

Post by Daniel Egitto