Marijuana is becoming legalized and decriminalized to the point that more than 63 percent of Americans have access to medical and recreational cannabis. But researchers and policy experts still don’t know very much about the long-term health effects.

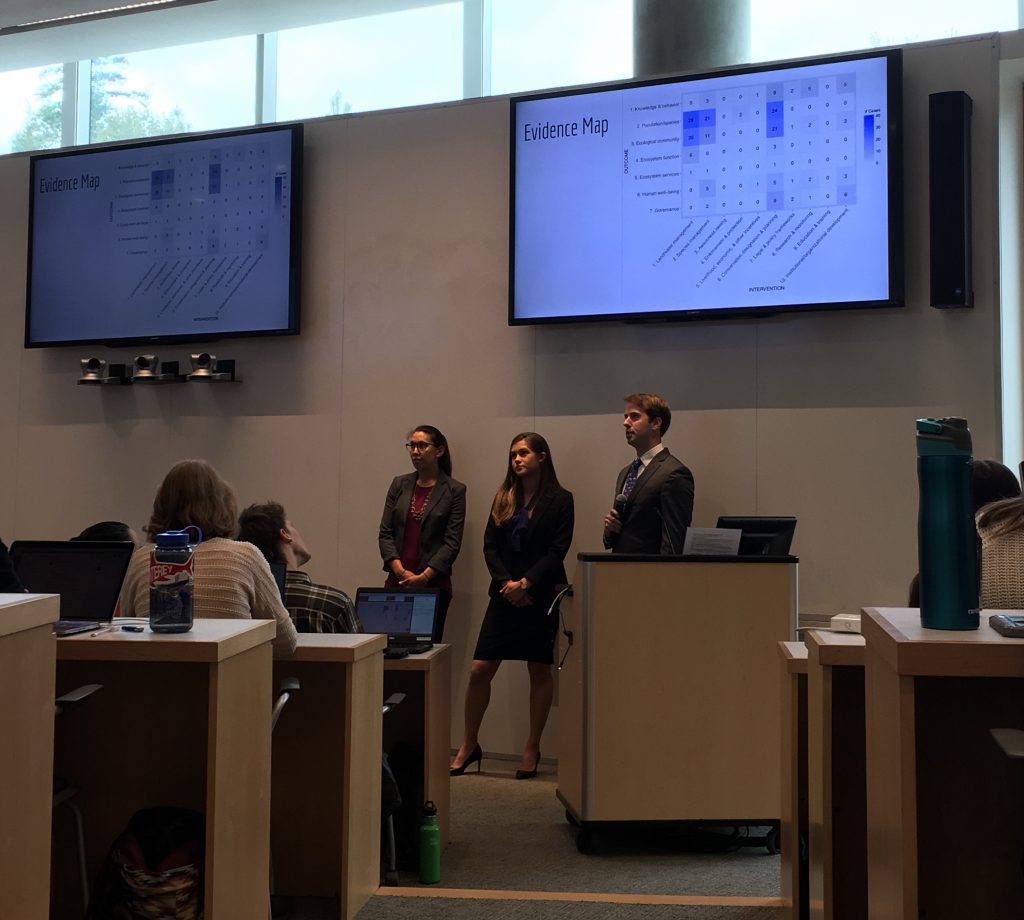

The 2019 annual symposium by Duke’s Center on Addiction & Behavior Change, “Altered States of Cannabis Regulation: Informing Policy with Science,” provided some scientific answers. Madeline Meier, assistant professor of Psychology at Arizona State University and a former Duke post-doc, spoke about her longitudinal research projects that offer critical insights about the long-term effects of cannabis use.

Meier investigates the relationship between cannabis use and IQ in a 38-year-long study that has been collecting data on a group of 1,000 people born in New Zealand since birth. Longitudinal studies like this that follow the same group of individuals across their lifespan are vital to understanding the effects of extended cannabis use on the human body, but they are difficult to conduct and keep funded. The 95 percent retention rate of this study is quite impressive and provides much-needed data.

Madeline Meier of Arizona State University

The researchers had tested the babies’ IQ at early childhood, then conducted regular IQ and cannabis use assessments between the ages of 18 and 38. They found that participants who heavily used weed for extended periods of time experienced a significant IQ drop, as well as other impairments in learning and memory skills. Specifically, users who had three or more clinical diagnoses of cannabis dependency, defined as compulsive use despite physical, legal, or social problems caused by the drug, showed an average 6-point IQ drop over the years. Those who only tried the drug a few times showed no decline, and those who never used weed showed a 1-point IQ increase.

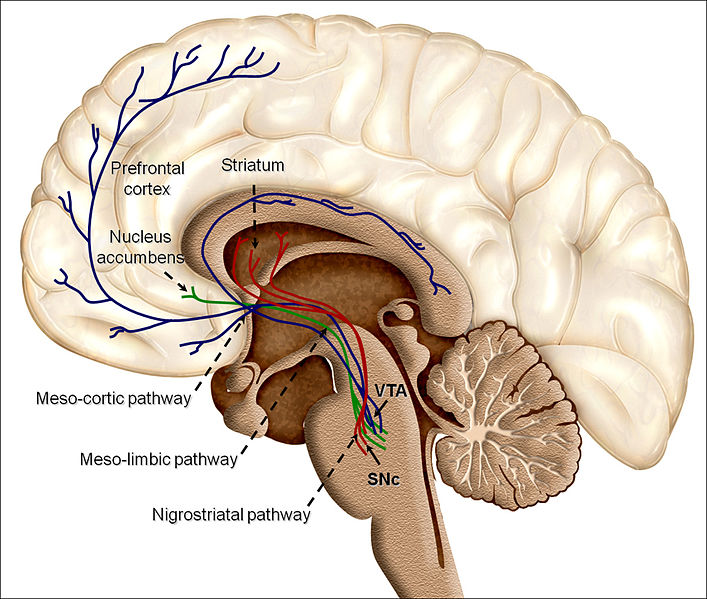

Notably, however, the results depended on age of onset and level of use. Meier emphasized that her results do not support the common misconception that any amount of weed use can immediately lead to IQ decline. To the contrary, Meier’s team found that short-term, low-level use did not have any effect on IQ; only heavy users suffered the negative effects. The age of onset of cannabis use was critical, too: Adolescents were more vulnerable to the drug’s harms, with study participants who started using as adolescents showing an 8-point drop in IQ points. Given what we know about adolescents’ affinity for risky behavior, specifically around experimentation with drugs, this finding is particularly worrisome.

In addition to causing cognitive impairment, persistent cannabis use jeopardizes people’s psychosocial functioning as well. The Dunedin longitudinal study has also revealed that people who continued to use weed despite multiple dependency diagnoses experienced downward social mobility, relationship problems, antisocial workplace behavior, financial difficulties, and even higher numbers of traffic convictions. In short, social life is likely to be perilous for heavy weed users.

While some have suggested that the harmful effects of weed might be caused not by the drug itself but by the reduced years of education, low socioeconomic status, mental health problems, or simultaneous use of tobacco, alcohol or other drugs among weed users, Meier and her team found that the impairments persisted even when these factors were accounted for. Cannabis alone was responsible for the effects reflected in Meier’s research. In fact, there is limited evidence for the opposite causational link: weed use may be the cause of mental health problems rather than being caused by them. One study found a weak correlation between years of marijuana use and depression, but Meier was careful to point out that it would take “a lot of cannabis use to lead to clinically diagnosed depression.”

Given this data, Meier called on the policy-makers in the room to focus their efforts on delaying the onset of cannabis use in youth and encouraging cessation (especially among adolescents). In appealing to the researchers, she underlined the need for additional longitudinal studies into the mechanisms and parameters of cannabis use that produce long-term impairments.

As public and political support of marijuana legalization grows, we must be careful not to underestimate the dangers of the drug. Without knowing the full extent of the risks and benefits of weed, policy-makers cannot effectively promote public health, safety, and social equity.