Of the few universal human experiences, death remains the least understood. Whether we avoid its mention or can’t stop thinking about it, whether we are terrified or mystified by it, none of us know what death is really like. Turns out, neither do the experts who spend every day around it.

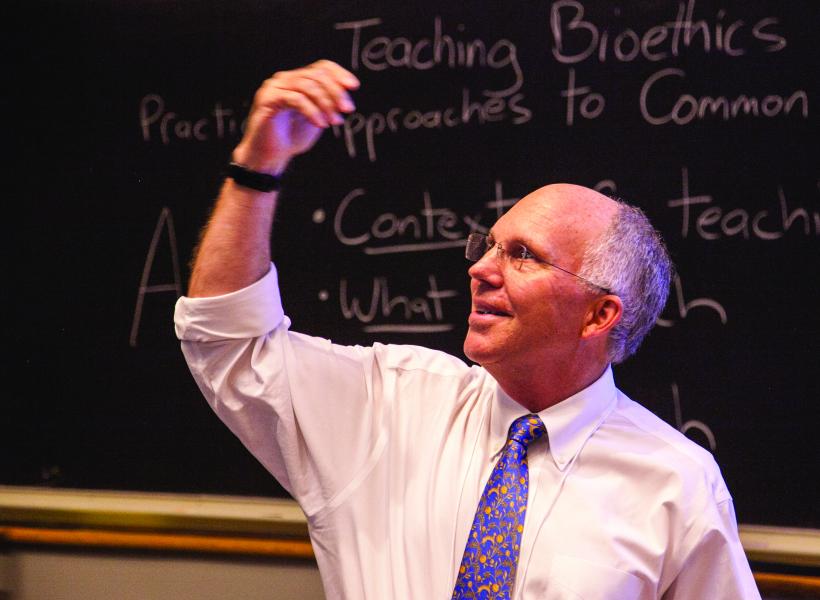

This was the overarching lesson of Dr. Robert Truog’s McGovern Lecture at Trent Semans Center for Health Education, titled “Defining Death: Persistent Problems and Possible Solutions.”

Dr. Truog is this year’s recipient of the McGovern Prize, an award honoring individuals who have made outstanding contributions to the art and science of medicine. Truog is a professor of medical ethics, anesthesiology and pediatrics and director of the center for bioethics at Harvard Medical School. He is intimately familiar with death, not only through his research and writings, but through his work as a pediatric intensive care doctor at Boston Children’s Hospital. Truog is also the author of the current national guidelines for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit.

In short, Truog knows a lot about death. Yet certain questions about the end of life remain elusive even to him. In his talk, he spoke about the biological, sociological, and ethical challenges involved in drawing the boundary between life and death. While some of these challenges have been around for as long as humans have, certain ones are novel, brought on by technological advancements in medicine that allow us to prolong the functioning of vital organs, mainly the brain and the heart.

The “irreversible cessation of function” of these organs results in brain and cardiac death, respectively. When both occur together, the patient is declared biologically dead. When they don’t, such as when all brain function except for those that support the patient’s digestive system is lost, for instance, the patient can be legally alive without any hope of recovery of consciousness.

According to Truog, it is in these moments of life after the loss of almost every brain function that we realize “death is a social construct.” This claim likely sounds counterintuitive, if not entirely nonsensical, as dying is the moment we have the least control over our biology. What Dr. Truog means, however, is that as technology continues to mend failures of biology that would have once been fatal, our social and philosophical understanding of dying, what he calls “person death” will increasingly separate from the end of the body’s biological function.

Biologically, death is the moment when homeostasis, the body’s internal state of equilibrium including body temperature, pH levels and fluid balance, fails and entropy prevails.

Personhood, however, is not mere homeostasis. Dr. Truog cited Robert Veatch, ethicist at Georgetown University, in defining person death as the “irreversible loss of that which is essentially significant to the nature of man.” For those patients who are kept alive by ventilators and who have no hope of regaining consciousness, that essentially significant nature appears to have been lost.

Nonetheless, for loved ones, signs like spontaneous breathing, which can occur in patients in persistent vegetative state, intuitively feel like signs of life. This intuitive sign of life is what made Jahi McMath’s parents refuse an Oakland California hospital’s declaration that their daughter was dead. A ventilator kept the 13-year-old breathing, even though she had been declared brain-dead. After much conflict, McMath’s parents moved her to a hospital in New Jersey, one of just two states where families can reject brain death if it does not align with their religious beliefs. In the end, McMath had two death certificates that were five years apart.

Muslim cemetery at sunset in Marrakech Morocco.

(Mohamed Boualam via Wikimedia commons)

The emotional toll of such an ordeal is immense, as the media outcry around McMath made more than clear. There are more concrete, quantifiable costs to extending biological function beyond the end of personhood: the U.S. is facing an organ shortage. As people are kept on life support for longer periods, it is going to become increasingly difficult for patients who desperately need organs to find donors.

In closing, Dr. Truog reminded us that “in the spectrum between alive and dead, we set the threshold… Death is not a binary state, but a complex social choice.” People will likely continue to disagree about where we should set the threshold, especially as technology develops.

However, if we want to have a thoughtful discussion that respects the rights, wishes, and values of patients, loved ones, and everybody else who will one day face death, we need to first agree that there is a choice to be made.

Guest Post by Deniz Ariturk, Science & Society graduate student