Ghost bikes are a haunting site. The white-painted bicycles, often decorated with flowers or photographs, mark the locations where cyclists have been hit and killed on the street.

A Ghost Bike located in Chapel Hill, NC.

Four of these memorials currently line the streets of Durham, and the statistics on non-fatal crashes in the community are equally sobering. According to data gathered by the North Carolina Department of Transportation, Durham county averaged 23 bicycle and 116 pedestrian crashes per year between 2011 and 2015.

But a team of Duke researchers say these grim crash data may also reveal clues for how to make Durham’s streets safer for bikers, walkers, and drivers.

This summer, a team of Duke students partnered with Durham’s Department of Transportation to analyze and map pedestrian, bicycle and motor vehicle crash data as part of the 10-week Data+ summer research program.

In the Ghost Bikes project, the team created an interactive website that allows users to explore how different factors such as the time-of-day, weather conditions, and sociodemographics affect crash risk. Insights from the data also allowed the team to develop policy recommendations for improving the safety of Durham’s streets.

“Ideally this could help make things safer, help people stay out of hospitals and save lives,” said Lauren Fox, a Duke cultural anthropology major who graduated this spring, and a member of the DATA+ Ghost Bikes team.

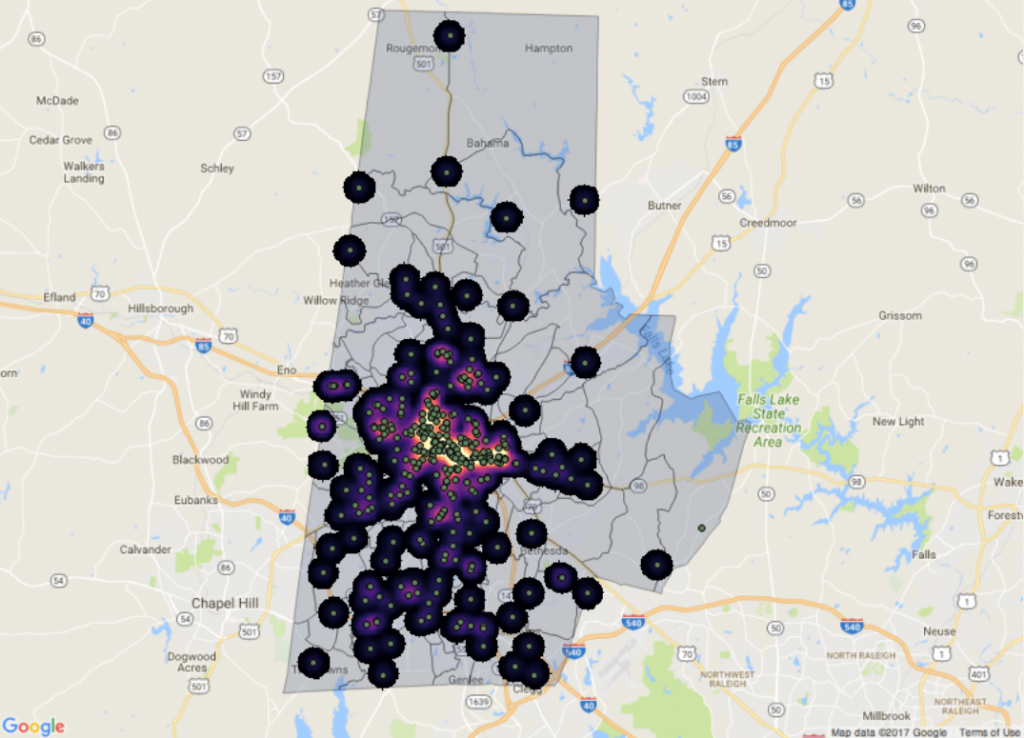

A heat map from the team’s interactive website shows areas with the highest density of bicycle crashes, overlaid with the locations of individual bicycle crashes.

The final analysis showed some surprising trends.

“For pedestrians the most common crash isn’t actually happening at intersections, it is happening at what is called mid-block crossings, which happen when someone is crossing in the middle of the road,” Fox said.

To mitigate the risks, the team’s Executive Summary includes recommendations to install crosswalks, median islands and bike lanes to roads with a high density of crashes.

They also found that males, who make up about two-thirds of bicycle commuters over the age of 16, are involved in 75% of bicycle crashes.

“We found that male cyclists over age 16 actually are hit at a statistically higher rate,” said Elizabeth Ratliff, a junior majoring in statistical science. “But we don’t know why. We don’t know if this is because males are riskier bikers, if it is because they are physically bigger objects to hit, or if it just happens to be a statistical coincidence of a very unlikely nature.”

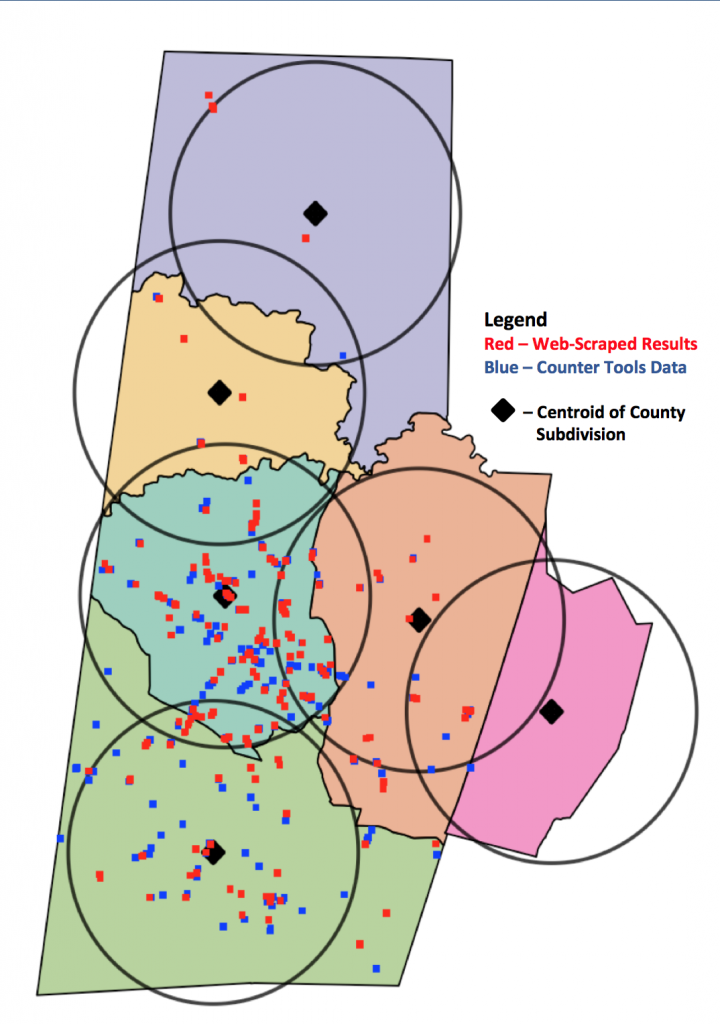

To build their website, the team integrated more than 20 sets of crash data from a wide variety of different sources, including city, county, regional and state reports, and in an array of formats, from maps to Excel spreadsheets.

“They had to fit together many different data sources that don’t necessarily speak to each other,” said faculty advisor Harris Solomon, an associate professor of cultural anthropology and global health at Duke. The Ghost Bikes project arose out of Solomon’s research on traffic accidents in India, supported by the National Science Foundation Cultural Anthropology Program.

In Solomon’s Spring 2017 anthropology and global health seminar, students explored the role of the ghost bikes as memorials in the Durham community. The Data+ team approached the same issues from a more quantitative angle, Solomon said.

“The bikes are a very concrete reminder that the data are about lives and deaths,” Solomon said. “By visiting the bikes, the team was able to think about the very human aspects of data work.”

“I was surprised to see how many stakeholders there are in biking,” Fox said. For example, she added, the simple act of adding a bike lane requires balancing the needs of bicyclists, nearby residents concerned with home values or parking spots, and buses or ambulances who require access to the road.

“I hadn’t seen policy work that closely in my classes, so it was interesting to see that there aren’t really simple solutions,” Fox said.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHIRqhdb7YQ&w=629&h=354]

Data+ is sponsored by Bass Connections, the Information Initiative at Duke, the Social Science Research Institute, the departments of Mathematics and Statistical Science and MEDx.

Other Duke sponsors include DTECH, Duke Health, Sanford School of Public Policy, Nicholas School of the Environment, Development and Alumni Affairs, Energy Initiative, Franklin Humanities Institute, Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, Office for Information Technology and the Office of the Provost, as well as the departments of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Computer Science, Biomedical Engineering, Biostatistics & Bioinformatics and Biology.

Government funding comes from the National Science Foundation. Outside funding comes from Accenture, Academic Analytics, Counter Tools and an anonymous donation.

Community partnerships, data and interesting problems come from the Durham Police Department, Durham Neighborhood Compass, Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Duke Marine Lab, Center for Child and Family Policy, Northeast Ohio Medical University, TD Bank, Epsilon, Duke School of Nursing, University of Southern California, Durham Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Commission, Duke Surgery, MyHealth Teams, North Carolina Museum of Art and Scholars@Duke.

Writing by Kara Manke; video by Lauren Mueller and Summer Dunsmore

Guest Post by Greer Arthur, a postdoctoral researcher at NC State

Guest Post by Greer Arthur, a postdoctoral researcher at NC State

Guest post by Stella Wang, Class of 2019

Guest post by Stella Wang, Class of 2019

Post by Kara Manke

Post by Kara Manke