Seventy percent of the United States population will have tried marijuana by the age of 30. As the debate on the legalization of the most commonly used illicit drug continues throughout the country, researchers like William Copeland, PhD, and Sherika Hill, PhD, from the Duke Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences are interested in patterns of marijuana use and abuse in the first 30 years of life.

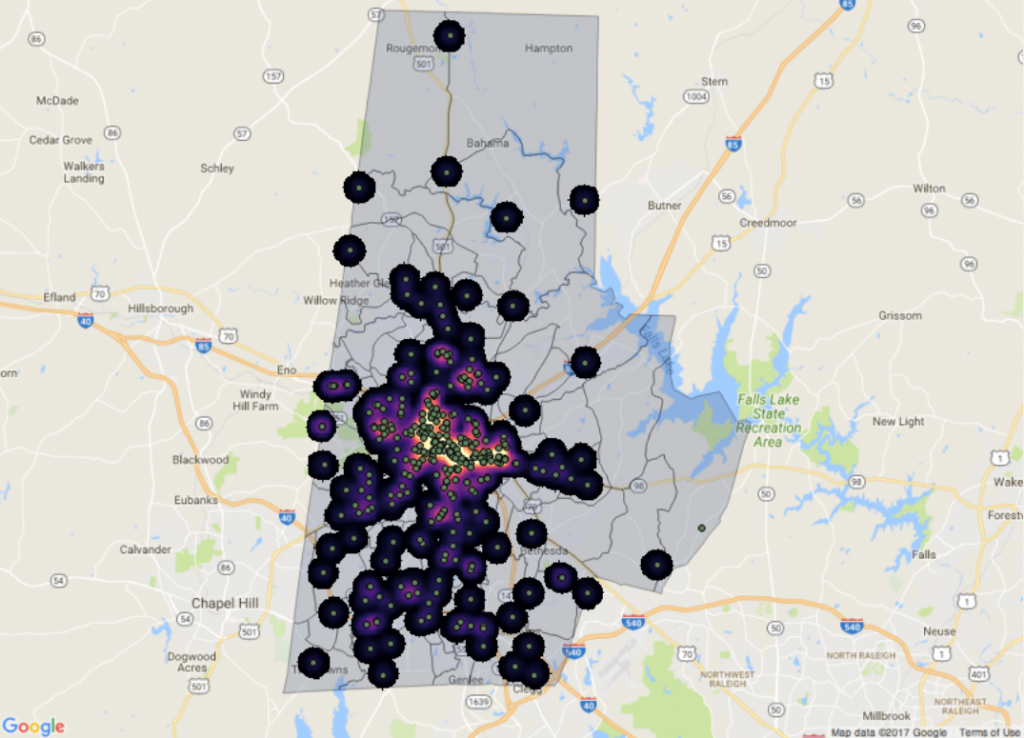

The Great Smoky Mountain Study set out in 1992 to observe which factors contributed to emotional and behavioral problems in children growing up in western North Carolina. The study included over 1,000 children, including nearly 400 living on the Cherokee reservation. In addition to its intended purpose, the data collected has proven invaluable to understanding how kids and young adults are forming their relationship with cannabis.

The Great Smoky Mountains Study collected extensive medical and behavioral research from 11 counties in western North Carolina.

Using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and patterns of daily use of the drug, Copeland and Hill found some unsurprising patterns: peak use of the drug is during young adulthood (ages 19-21), when kids are moving out of the home to college or to live alone.

But while most people adjust to this autonomy and eventually stop their usage of the drug, a small percentage of users (7%) keep using into their adulthood. Hill and Copeland have observed specific trends that apply both to this chronic user group as well as an even smaller percentage of users (4%) who begin using at a later stage in life than most people, termed the delayed-onset problematic users.

Looking at the demographics of the various types of users, Hill and Copeland found that males are twice as likely to engage in marijuana use to any extent than females. Of those who do use the drug, African Americans are five times more likely to be delayed-onset users, while Native Americans are twice as likely to decrease their use before it becomes problematic.

For both persistent and delayed-onset problematic users, family instability during childhood was 2-4 times more likely than in non-problematic users.

Persistent users were more likely to have endured anxiety throughout childhood, and delayed-onset users were more likely to have experienced some kind of trauma or maltreatment in childhood than other types of users.

The identification of these trends could prove a vital tool in predicting and preventing marijuana abuse, and the importance of this understanding is evidenced in the data collected that elucidates outcomes of marijuana use.

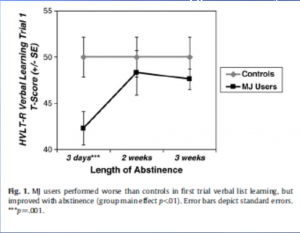

Looking at various measures of social and personal success, the team identified patterns with a resounding trend: recent use of marijuana is indicative of poorer outcomes. Physical health and financial or educational outcomes displayed the worst outcomes in chronic and delayed-onset users. Finally, criminal behavior was increased in every group that used; in other words, regardless of the extent of use, every group with use of marijuana fared worse than the group that abstained.

The results of Copeland and Hill’s work has important implications as legislators debate the legalization of marijuana. While understanding these patterns of use and their outcomes can provide useful insight on the current patterns of usage, decriminalization will certainly change the way marijuana is manufactured and consumed, and will thus also affect these patterns.

By Sarah Haurin

By Sarah Haurin

With incredible increases in life expectancy, from

With incredible increases in life expectancy, from  Post by Lydia Goff

Post by Lydia Goff

Post by Daniel Egitto

Post by Daniel Egitto

(

(