Who makes riskier decisions, the young or the old? And what matters more in our decisions as we age — friends, health or money? The answers might surprise you.

Kendra Seaman works at the Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development and is interested in decision-making across the lifespan.

Duke postdoctoral fellow Kendra Seaman, Ph.D. uses mathematical models and brain imaging to understand how decision-making changes as we age. In a talk to a group of cognitive neuroscientists at Duke, Seamen explained that we have good reason to be concerned with how older people make decisions.

Statistically, older people in the U.S. have more money, and additionally more expenditures, specifically in healthcare. And by 2030, 20 percent of the US population will be over the age of 65.

One key component to decision-making is subjective value, which is a measure of the importance a reward or outcome has to a specific person at a specific point in time. Seaman used a reward of $20 as an example: it would have a much higher subjective value for a broke college student than for a wealthy retiree. Seaman discussed three factors that influence subjective value: reward, cost, and discount rate, or the determination of the value of future rewards.

Brain imaging research has found that subjective value is represented similarly in the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) across all ages. Despite this common network, Seaman and her colleagues have found significant differences in decision-making in older individuals.

The first difference comes in the form of reward. Older individuals are likely to be more invested in the outcome of a task if the reward is social or health-related rather than monetary. Consequently, they are more likely to want these health and social rewards sooner and with higher certainty than younger individuals are. Understanding the salience of these rewards is crucial to designing future experiments to identify decision-making differences in older adults.

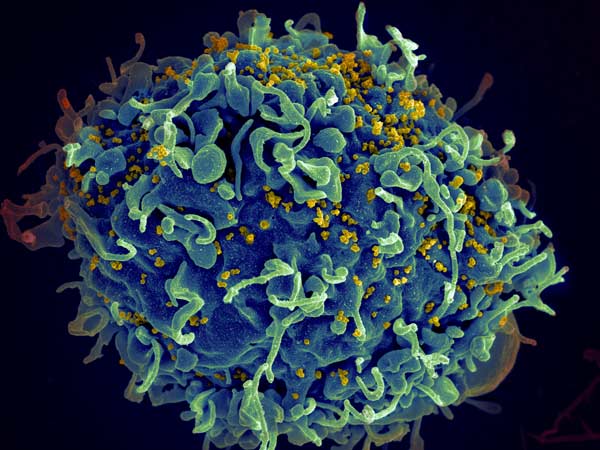

A preference for positive skew becomes more pronounced with age.

Older individuals also differ in their preferences for something called “skewed risks.” In these tasks, positive skew means a high probability of a small loss and a low probability of a large gain, such as buying a lottery ticket. Negative skew means a low probability of a large loss and a high probability of a small gain, such as undergoing a common medical procedure that has a low chance of harmful complications.

Older people tend to prefer positive skew to a greater degree than younger people, and this bias toward positive skew becomes more pronounced with age.

Understanding these tendencies could be vital in understanding why older people fall victim to fraud and decide to undergo risky medical procedures, and additionally be better equipped to motivate an aging population to remain involved in physical and mental activities.

Post by undergraduate blogger Sarah Haurin

Post by Victoria Priester

Post by Victoria Priester

Post by Alexis Owens

Post by Alexis Owens