Duke senior Jesse Mangold has had an interest in the intersection of medicine and research since high school. While he took electives in a program called “Science, Medicine, and Research,” it wasn’t until the summer after his first year at Duke that he got to participate in research.

As a member of the inaugural class of Huang fellows, Mangold worked in the lab of Duke assistant professor Christina Meade on the compounding effect of HIV and marijuana use on cognitive abilities like memory and learning.

The following summer, Mangold traveled to Honduras with a group of students to help with collecting data and also meeting the overwhelming need for eye care. Mangold and the other students traveled to schools, administered visual exams, and provided free glasses to the children who needed them. Additionally, the students contributed to a growing research project, and for their part, put together an award-winning poster.

Mangold’s (top right) work in Honduras helped provide countless children with the eye care they so sorely needed.

Returning to school as a junior, Mangold wanted to focus on his greatest research interest: the molecular mechanisms of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Mangold found a home in the Permar lab, which investigates mechanisms of mother-to-child transmission of viruses including HIV, Zika, and Cytomegalovirus (CMV).

From co-authoring a book chapter to learning laboratory techniques, he was given “the opportunity to fail, but that was important, because I would learn and come back the next week and fail a little bit less,” Mangold said.

In the absence of any treatment, mothers who are HIV positive transmit the virus to their infants only 30 to 40 percent of the time, suggesting a component of the maternal immune system that provides at least partial protection against transmission.

The immune system functions through the activity of antibodies, or proteins that bind to specific receptors on a microbe and neutralize the threat they pose. The key to an effective HIV vaccine is identifying the most common receptors on the envelope of the virus and engineering a vaccine that can interact with any one of these receptors.

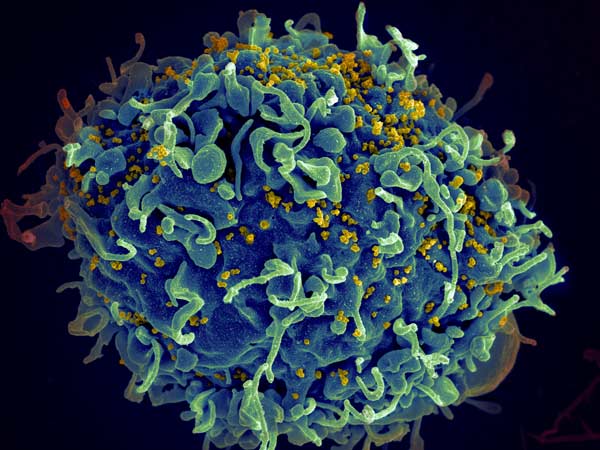

This human T cell (blue) is under attack by HIV (yellow), the virus that causes AIDS. Credit: Seth Pincus, Elizabeth Fischer and Austin Athman, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health

Mangold is working with Duke postdoctoral associate Ashley Nelson, Ph.D., to understand the immune response conferred on the infants of HIV positive mothers. To do this, they are using a rhesus macaque model. In order to most closely resemble the disease path as it would progress in humans, they are using a virus called SHIV, which is engineered to have the internal structure of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and the viral envelope of HIV; SHIV can thus serve to naturally infect the macaques but provide insight into antibody response that can be generalized to humans.

The study involves infecting 12 female monkeys with the virus, waiting 12 weeks for the infection to proceed, and treating the monkeys with antiretroviral therapy (ART), which is currently the most effective treatment for HIV. Following the treatment, the level of virus in the blood, or viral load, will drop to undetectable levels. After an additional 12 weeks of treatment and three doses of either a candidate HIV vaccine or a placebo, treatment will be stopped. This design is meant to mirror the gold-standard of treatment for women who are HIV-positive and pregnant.

At this point, because the treatment and vaccine are imperfect, some virus will have survived and will “rebound,” or replicate fast and repopulate the blood. The key to this research is to sequence the virus at this stage, to identify the characteristics of the surviving virus that withstood the best available treatment. This surviving virus is also what is passed from mothers on antiretroviral therapy to their infants, so understanding its properties is vital for preventing mother-to-child transmission.

As a Huang fellow, Mangold had the opportunity to present his research on the compounding effect of HIV and marijuana on cognitive function.

Mangold’s role is looking into the difference in viral diversity before treatment commences and after rebound. This research will prove fundamental in engineering better and more effective treatments.

In addition to working with HIV, Mangold will be working on a project looking into a virus that doesn’t receive the same level of attention as HIV: Cytomegalovirus. CMV is the leading congenital cause of hearing loss, and mother-to-child transmission plays an important role in the transmission of this devastating virus.

Mangold and his mentor, pediatric resident Tiziana Coppola, M.D., are authoring a paper that reviews existing literature on CMV to look for a link between the prevalence of CMV in women of child-bearing age and whether this prevalence is predictive of the number of children suffer CMV-related hearing loss. With this study, Mangold and Coppola are hoping to identify if there is a component of the maternal immune system that confers some immunity to the child, which can then be targeted for vaccine development.

After graduation, Mangold will continue his research in the Permar lab during a gap year while applying to MD/PhD programs. He hopes to continue studying at the intersection of medicine and research in the HIV vaccine field.

Post by undergraduate blogger Sarah Haurin