How can we understand how humans make decisions? How do we measure the root of motivation?

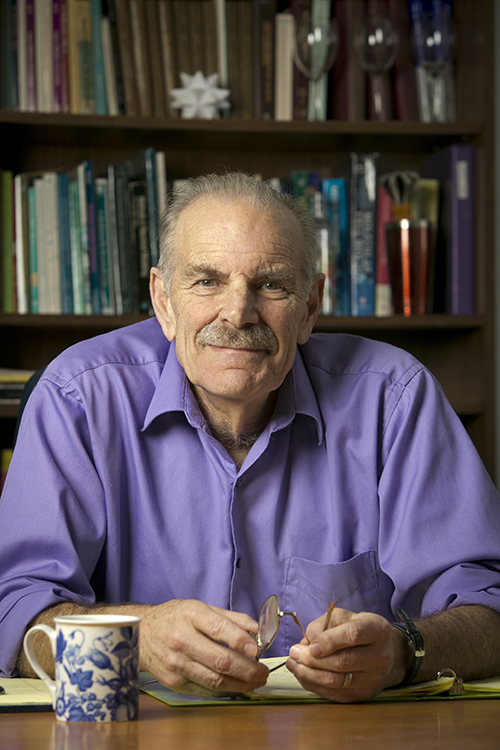

Gregory Samanez-Larkin, an assistant professor in Psychology & Neuroscience at Duke, uses neuroeconomic and neuromarketing approaches to seek answers to these questions. He combines experimental psychology and economics with neuroimaging and statistical analysis as an interdisciplinary approach to understanding human behavior.

From studying the risk tendencies in different age groups to measuring the effectiveness of informative messages in health decision-making,Samanez-Larkin’s diverse array of research reflects the many applications of neuroeconomics.

He finds that neuroeconomic and neurofinance tools can help spot vulnerabilities and characteristics within groups of people.

Though his Motivated Cognition & Aging Brain Lab at Duke, he would like to extend his work to finding interventions that would encourage healthier or optimal decision-making. Many financial organizations and firms are interested in these questions.

While Samanez-Larkin has produced some very influential research in the field, the path to his career was not a straightforward one.Raised in Flint, Michigan, he found that the majority of people around him were not very career-oriented. He found a passion for wakeboarding, visual art, and graphic design.

As an undergraduate at the University of Michigan-Flint, he was originally on a pre-business track. But after taking various psychology courses and assisting in research, Samanez-Larkin was captivated by the excitement and the advances in brain imaging at the time.

However, misconceptions about the field caused him to question whether or not going into research was the right fit, leading him to seek jobs in marketing and advertising instead. But in job interviews, he ended up questioning the methods and the ways companies explained the appeal of different ways of advertising. Realizing that he really enjoyed asking questions and evaluating how things work, he reconsidered pursuing science.

After a series of positive experiences in a research position in San Francisco, Samanez-Larkin began his graduate studies at Stanford University. The growing field of neuroeconomics — which combined his diverse set of interests in neuroscience, psychology, and economics — continued the “decade-long evolution” of Samanez-Larkin’s career.

Samanez-Larkin’s experiences in his career journey are reflected strongly in his approach to teaching.

“I feel like my primary responsibility is to help people become successful,” he says, as we sit comfortably on the sofas in his office.“Everything I do is for that.”

In his courses, Samanez-Larkin emphasizes the need to think critically and evaluate information, consistently asking questions like, “How do we know something works or not? How do I know how to evaluate if it works or not? How can I become a good consumer of scientific information?”

In his teaching, Samanez-Larkin hopes to set students up with usable, translatable skills that are applicable to any field.

Samanez-Larkin also hopes to support his students in the same way he received support from his previous mentors. “It’s cool to learn about how the brain works, but ultimately, I’m just trying to help people do something.”

Guest Post by Ariba Huda, NCSSM 2019

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62603270/AP_18332234595077.0.jpg)

Post by Anne Littlewood

Post by Anne Littlewood

eBike Central had a whole fleet of electric bikes, or “e-bikes,” on display for people to try out: mountain bikes, commuter bikes, cargo bikes and more. I tried out one of the mountain bikes and took it off-roading up a steep hill nearby (which I never would’ve been able to make up without the electric assist). Then just to mess around I tried out the “

eBike Central had a whole fleet of electric bikes, or “e-bikes,” on display for people to try out: mountain bikes, commuter bikes, cargo bikes and more. I tried out one of the mountain bikes and took it off-roading up a steep hill nearby (which I never would’ve been able to make up without the electric assist). Then just to mess around I tried out the “

(pic:

(pic:  The Duke Electric Vehicles team was also at the kickoff event, showcasing their vehicle that holds the

The Duke Electric Vehicles team was also at the kickoff event, showcasing their vehicle that holds the  Post by Will Sheehan

Post by Will Sheehan