“If you – as a human – want to know how somebody feels, for what might you look?” Professor Shaundra Daily asked the audience during an ECE seminar last week.

“Facial expressions.”

“Body Language.”

“Tone of voice.”

“They could tell you!”

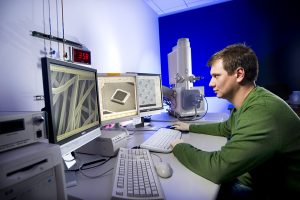

Over 50 students and faculty gathered over cookies and fruits for Dr. Daily’s talk on designing applications to support personal growth. Dr. Daily is an Associate Professor in the Department of Computer and Information Science and Engineering at the University of Florida interested in affective computing and STEM education.

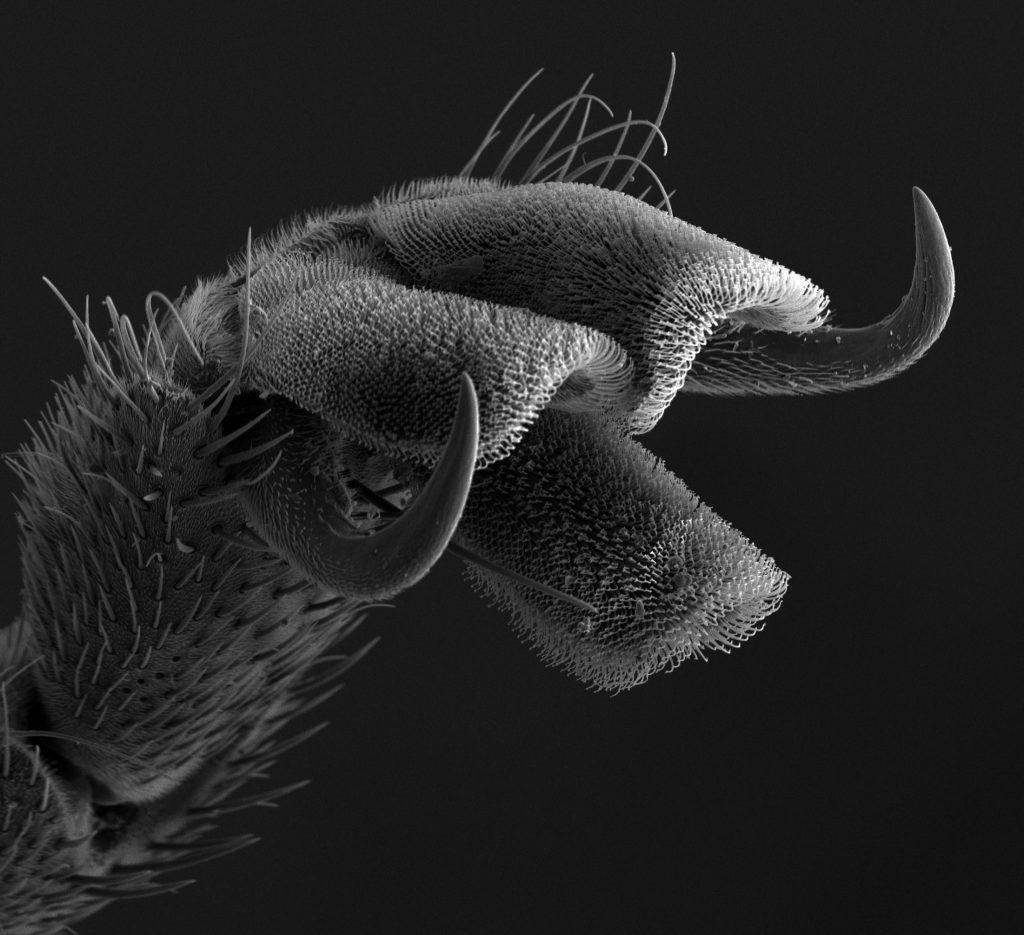

Dr. Daily explaining the various types of devices used to analyze people’s feelings and emotions. For example, pressure sensors on a computer mouse helped measure the frustration of participants as they filled out an online form.

Affective Computing

The visual and auditory cues proposed above give a human clues about the emotions of another human. Can we use technology to better understand our mental state? Is it possible to develop software applications that can play a role in supporting emotional self-awareness and empathy development?

Until recently, technologists have largely ignored emotion in understanding human learning and communication processes, partly because it has been misunderstood and hard to measure. Asking the questions above, affective computing researchers use pattern analysis, signal processing, and machine learning to extract affective information from signals that human beings express. This is integral to restore a proper balance between emotion and cognition in designing technologies to address human needs.

Dr. Daily and her group of researchers used skin conductance as a measure of engagement and memory stimulation. Changes in skin conductance, or the measure of sweat secretion from sweat gland, are triggered by arousal. For example, a nervous person produces more sweat than a sleeping or calm individual, resulting in an increase in skin conductance.

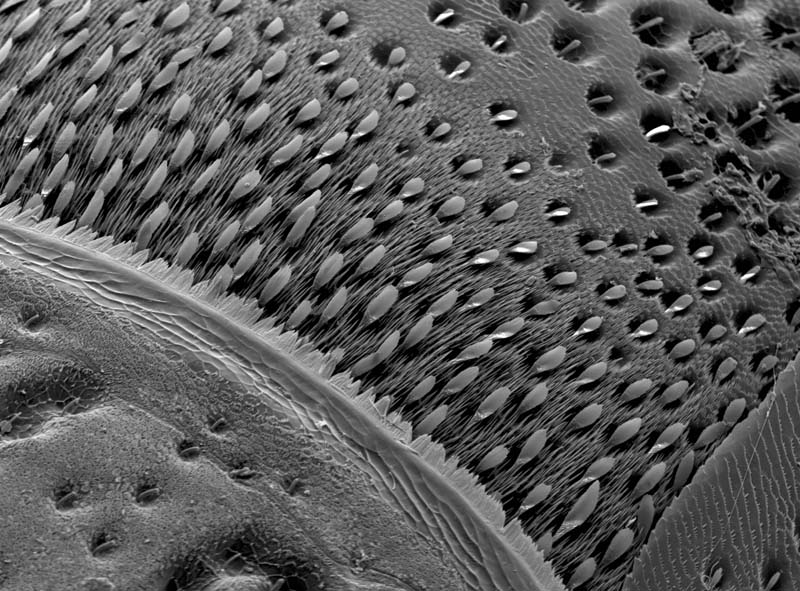

Galvactivators, devices that sense and communicate skin conductivity, are often placed on the palms, which have a high density of the eccrine sweat glands.

Applying this knowledge to the field of education, can we give a teacher physiologically-based information on student engagement during class lectures? Dr. Daily initiated Project EngageMe by placing galvactivators like the one in the picture above on the palms of students in a college classroom. Professors were able to use the results chart to reflect on different parts and types of lectures based on the responses from the class as a whole, as well as analyze specific students to better understand the effects of their teaching methods.

Project EngageMe: Screenshot of digital prototype of the reading from the galvactivator of an individual student.

The project ended up causing quite a bit of controversy, however, due to privacy issues as well our understanding of skin conductance. Skin conductance can increase due to a variety of reasons – a student watching a funny video on Facebook might display similar levels of conductance as an attentive student. Thus, the results on the graph are not necessarily correlated with events in the classroom.

Educational Research

Daily’s research blends computational learning with social and emotional learning. Her projects encourage students to develop computational thinking through reflecting on the community with digital storytelling in MIT’s Scratch, learning to use 3D printers and laser cutters, and expressing ideas using robotics and sensors attached to their body.

VENVI, Dr. Daily’s latest research, uses dance to teach basic computational concepts. By allowing users to program a 3D virtual character that follows dance movements, VENVI reinforces important programming concepts such as step sequences, ‘for’ and ‘while’ loops of repeated moves, and functions with conditions for which the character can do the steps created!

Dr. Daily and her research group observed increased interest from students in pursuing STEM fields as well as a shift in their opinion of computer science. Drawings from Dr. Daily’s Women in STEM camp completed on the first day consisted of computer scientist representations as primarily frazzled males coding in a small office, while those drawn after learning with VENVI included more females and engagement in collaborative activities.

VENVI is a programming software that allows users to program a virtual character to perform a sequence of steps in a 3D virtual environment!

In human-to-human interactions, we are able draw on our experiences to connect and empathize with each other. As robots and virtual machines grow to take increasing roles in our daily lives, it’s time to start designing emotionally intelligent devices that can learn to empathize with us as well.

Post by Anika Radiya-Dixit

Post and photo by Meg Shieh

Post and photo by Meg Shieh