Cataract surgery is often perceived as a garden-variety medical intervention akin to the colonoscopy, mammogram, or flu shot. But outside of higher-income countries, the following is not an understatement: eye care can be revolutionary.

It is estimated that, globally, 36 million people are blind; that around 90% of preventable blindness cases are demarcated within low and middle income countries; and that nearly 75% of blind individuals could regain their vision with medical intervention.

Today, cataract surgery can be performed for $100 or less and, with a practiced hand, in as little as three minutes.

In that context: a blind individual can completely regain their sight in the time it takes to brush their teeth. For the price of a discounted pair of running shoes.

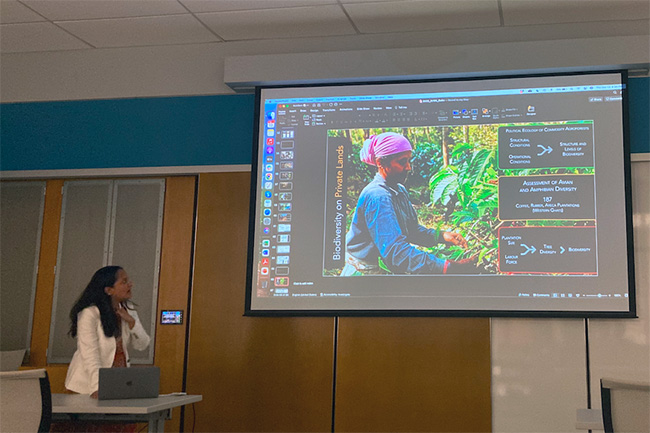

In late September, the Duke Global Ophthalmology Program hosted the A Vision for Ending Preventable Blindness panel to address the global scope of vision impairment, eye care interventions, and subsequent socioeconomic implications. Panelist Dr. Geoffrey Tabin, Professor of Ophthalmology and Global Medicine at Stanford University, characterized the nature of these eye conditions: “Glaucoma’s preventable, trachoma’s preventable, river blindness is preventable, vitamin A deficiency is preventable, even… diabetic changes [in vision] are preventable.” In fact, cataract surgery, in most cases, is a 100% and lasting cure.

What other health interventions boast similar statistics?

Panelist Dr. Jalikatu Mustapha, new Deputy Minister of Health of Sierra Leone, and moderator Dr. Lloyd Williams, director of Duke Global Ophthalmology Program, established a corneal transplantation program in Sierra Leone. Pictured above with a box of corneas, Williams performed the country’s first corneal transplant in 2021. Mustapha and Williams recounted a clinical experience that well-represents their objectives:

While operating in Sierra Leone, Mustapha and Williams worked with a patient completely blind since her teenaged years. After 29 years and a successful corneal transplant, she regained sight in one of her eyes. Walking out of the clinic, she saw a crying young woman and asked what was wrong. When the young woman responded, the patient recognized the woman’s voice, realizing that she was, in fact, her daughter. This would mark the first time she had physically seen one of her children. Her daughter was 19.

Over the course of his career, Williams has performed thousands of eye surgeries in Africa including, of course, a number of corneal transplants.

Despite the obvious efficacy of eye health interventions, blindness has little priority on the global health agenda nor in low income countries where preventable cases are disproportionately located. Tabin emphasized the “travesty” of this disconnect, describing blindness as “the lowest hanging fruit in global public health.”

Why is this the case?

NGOs and governments point to the high mortality rates of infectious diseases like HIV, malaria, cholera, COVID. Blindness is not fatal, they argue, it is an apples and oranges comparison, cataracts to Ebola.

A glance at notable foundations and charities with health-related mission statements cements this sentiment. For example, among its laundry list of initiatives, the Gates Foundation funds the fight against enteric and diarrheal diseases, HIV, malaria, neglected tropical diseases, pneumonia, and tuberculosis; the Rockefeller Foundation “established the global campaign against hookworm… seeded the development of the yellow fever vaccine… supported translational research for tools ranging from penicillin to polio… spurred AIDS vaccine development;” and the Wellcome Trust financially supports infectious disease, drug-resistant infection, and Covid-19 research.

Of course, this is not an effort to undermine the impact of these institutions but merely to point out a lack of urgency to redress blindness.

The panelists challenged this “if not fatal then not urgent” thinking. Tabin cited two poignant WHO estimates: 1) vision impairment contributes to an annual $411 billion global productivity loss, and 2) the cost of providing eye care to every in-need individual would be around $25 billion.

The US Department of Defense’s proposed 2024 fiscal year budget is $842 billion. If this funding was allocated towards eye care, every case of preventable blindness could be mitigated 33 times over in one year.

The downstream effects of blindness are substantial not only for the effected individual but for their family. In the absence of sufficient eye care, children with congenital cataracts, for example, will struggle/will not attend school; they will require care, potentially removing family members from the workforce; they will struggle to find employment; and, on average, they will have a life expectancy about a third of their age- and health-matched peers. Because 90% of preventable blindness is localized in low and middle income countries, community productivity and GDP may be significantly impacted by curable conditions.

Tabin explained that “blindness really perpetuates poverty” and, on the flip side of the same coin, “poverty really accentuates the suffering of blindness.” Through his work at Stanford, Tabin identified pockets of agricultural Northern California with mass migrant workforces and high rates of preventable blindness. Documentation concerns, language barriers, and/or lack of healthcare often prevents seasonal workers and immigrants from accessing and benefiting from care, comparable to that in low and middle income countries.

Dr. Bidya Pant, a leading ophthalmic surgeon, challenged this so-called eye care vacuum in a number of countries, including Myanmar, Uganda, and Nepal. His work speaks for itself. In 2016, Pant built six new hospitals, worked with a number of local monks to facilitate care, trained countless ophthalmology specialists, and completed 200,000 cataract surgeries. His high volume cataract surgery model dramatically decreased cost such that even individuals from the poorest communities in Nepal are still able to afford life-changing care.

In 1984 the population prevalence of blindness in Nepal was 0.84%. In 2015, it was just 0.35%.

Similar to Pant’s collaboration with the Myanmar monks, Mustapha, in her role as Sierra Leone’s Deputy Health Minister, has worked to increase access to eye care by training community healthcare workers who already provide maternal care, chronic disease management, vaccinations, etc. to rural communities lacking access to public health initiatives. Mustapha also advocates for a national prioritization and an integration of eye health “… into a strong health system that focuses on delivering quality healthcare that’s affordable to every Sierra Leonean across all life stages, whether they be pregnant women, babies, teenagers, adults, or elderly people, without financial consequences.”

Mustapha then posed the question: If you provide a child with a vaccine for measles or pneumonia and they later go blind from cataracts, have you really helped that child?

Of course not!

At face value, ending preventable blindness seems overly idealistic. But, let’s return to Tabin’s “low hanging fruit” analogy. As exemplified by the work of Tabin, Mustapha, Williams, and Pant, eye care is public health’s blueberry bush. Given proper investment and government initiative, this aim is arguably realistic. It’s just a matter of enough hands reaching for and plucking berries from the bush.

I will defer to Williams who best situated the scope of their mission. He said: “You could make a serious case that there [is] no intervention… for the dollar… that would send more girls in Africa to school than cataract surgery.”

If interested, you can watch the A Vision for Ending Preventable Blindness Panel here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3fSw5w2nk6k

Post by Alex Clifford, Class of 2024

By Victoria Wilson, Class of 2023

By Victoria Wilson, Class of 2023