“Krithi Karanth is…” begins a long sentence if not pruned, so I will settle on the following: Dr. Karanth is the Chief Conservation Scientist and Director at the Centre for Wildlife Studies in India, an adjunct professor in the Nicholas School at Duke, and a Vogue Woman of the Year.

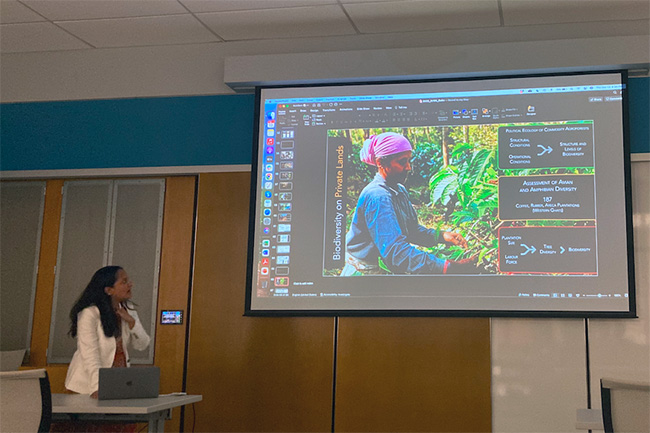

On Oct. 13, she visited her alma mater to catch us up on her work.

Karanth grew up in close contact with an abundance of wildlife as the daughter of tiger biologist Dr. Ullas K. Karanth in India. Her first experience in the jungle was at the ripe age of one, and she credits this “sheer joy of watching nonhumans uninterrupted” as the basis for her deep concern and care for wildlife.

She received her Ph.D from the Nicholas School after scouring historic hunting journals and interviewing Indian wildlife scientists to build a database that documents the havoc wreaked on wildlife populations in India, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century. The results are gut-wrenching, among them: an estimated 96% plunge in the lion population, 67% drop in tigers, and a 62% decline in wolves.

After thirteen years studying and researching in the U.S., Karanth returned home to India, where she felt her impact could be greater.

Today, large British hunting parties are no longer the main cause of species decline in India. Instead, man and beast find themselves stepping on each other’s toes and tails more and more as towns expand and animals like elephants and leopards lose their habitats.

At the Centre for Wildlife Studies, Karanth’s work focuses on mitigating the most prevalent problems in human-wildlife interaction: crop and property damage, livestock predation, and human injury and death.

Her tactics for doing so are expansive. At CWS, she leads several initiatives targeting different sides of the problem.

WildSeve deploys timely assistance to people, most often farmers, dealing with destructive wildlife encounters. Farmers can call a toll free number, and a member of the team will ride out to their farm to help document the incident and file a claim for government compensation, allowing farmers to complete what would otherwise be an arduous and expensive legal process. In “peak season,” between October and November when many farmers are growing a cover crop known to attract elephants, WildSeve deploys as many as thirty conflict responders per day.

The goal of these interactions is not simply response, but mitigation. WildSeve helps farmers understand what factors increase the likelihood of human-wildlife conflict (HWC) and how to avoid these encounters in the future.

Another project in the works, WildCarbon, will assist farmers in transitioning their land from agriculture to carbon-sequestering agro-forests in places where the benefits can outweigh the costs.

Karanth says that trust is key to ensuring that the advice from the team is well-received. It is often difficult to convince a farmer to change their practices. Farming technique is both a careful science and the basis of a farmer’s livelihood. The project is in its seventh year, and Karanth says it has taken time for farmers to see that their assistance works. One factor that helps build this trust is that many members of the WildSeve team are locals in the communities.

Another program, WildShaale, is designed to foster understanding and appreciation for local wildlife in schoolchildren. Karanth pointed out that many school-age children easily recognize a kangaroo despite their lack of proximity to or interaction with the Australian marsupial, but could not identify the Indian wolf native to their backyard.

For children living in communities that come in close contact with wildlife, their perception of the animals is often one of fear. Karanth said the curiosity and empathy that WildShaale nurtures is critical to creating communities that have a net positive relationship with their animal neighbors. By fostering this empathy, violence becomes a last resort when dealing with wildlife conflicts.

After Karanth’s talk, I grabbed a chai latte from Beyu Cafe and sat down in Penn Pavilion for New York Times columnist Bret Stephens’ chat on cross-partisan conversation. At the time, I didn’t see much connection between the two events, but in retrospect, it is there. Both talks touched on that attempt at harmony, respect, and civil discourse I so often find myself craving: for Karanth, it’s between animals and people; for Stephens, people and people.

As I got ready to write this article, I turned on my GE digital clock radio to keep me company. I debated switching to a podcast, but then the host mentioned elephants and — given their relevance to task — I leaned in a little closer.

WUNC was playing this week’s segment of the TED Radio Hour, which centered on finding resolutions in situations of conflict. The woman being interviewed was discussing her own solution to elephant-human conflict in Kenya: beehives.

I will leave it to the reader to find out how, but the remainder of the segment drove home my key takeaway from hearing Karanth speak: Seeking out simple, yet innovative answers to human-wildlife conflict, a life or death issue, can teach us a lot about the importance of finding solutions to interpersonal conflict.

Post by Addie Geitner, Class of 2025