Picture a comic book. Maybe you think of Superman or the Hulk, all cosmic green and razzmic berry, pressed into the glossy pages of your favorite childhood graphic novel. Or maybe you think of the Sunday paper. Calvin and Hobbes inked between the op-eds and the sports column. Maybe you think of punk rock zines, or political cartoons, or Mad magazine.

Now, put your first thought aside. Walk to the Duke Medical School library and descend to the first floor. Nestled in the quiet reading room, among the serious tomes on pancreatic enzymes and brain anatomy, is a collection of comic books.

They don’t chronicle the kryptonite of superheroes or the adventures of Asterix. Instead, the curated Graphic Medicine Collection features soldiers with PTSD, mothers of children with Down Syndrome, and transgender patients’ gender-affirming care. They illustrate child loss, chronic illness, addiction, anxiety, autism, epilepsy, COVID, cancer, heart disease, reproductive health, and so on and so forth.

In 2007, physician and cartoonist Ian Williams coined the term “graphic medicine.” He writes that the “use of the word ‘medicine’ was not meant to connote the foregrounding of doctors over other healthcare professionals or over patients or comics artists, but, rather the suggestion that use of comics might have some sort of therapeutic potential – ‘medicine’ as in the bottled panacea, rather than the profession.”

Duke’s Graphic Medicine Collection seeks to destigmatize, depicting everything from a patient’s experience with terminal cancer to STI prevention. Unsurprisingly, comics have long been used to educate and to challenge social taboos.

In 1954, they were controversial enough to trigger a congressional hearing. Despite grossing nearly $75 million in nickels and dimes (the cost of a comic in 1948), comic books fed the flames (often literally) of moral panics that came to dominate the Cold War era.

In 1949, a small town Missouri girl scout troop burned a six foot tall stack of comics at the behest of their parents, teachers, and the local priest. This event followed the publication of an article written by New York City psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham which drew a correlation between the occasional vulgar language and violent imagery in comic book and increased incidence of juvenile delinquency.

Although Congress found no correlation between comics and criminal activity, ultimately disagreeing with Wertham, the comic industry created the “Comics Code Authority” out of fear of government censorship. Comics with everything from violence to werewolves, zombies, vampires and ghosts were banned. Though the comic code undeniably cowed their content, cartoonists continued to use the medium to criticize and confront stigmas.

In the 60s and 70s, for example, “subversive women cartoonists, queer cartoonists, [and] cartoonists of color” disseminated their work in political circles. Later, in 1989, cartoonist Garry Trudeau depicted the first openly gay comic character Andy Lippincott’s diagnosis with HIV/AIDS. Though some gay activists criticized Trudeau’s portrayal, his comics nonetheless challenged the public’s stereotypes, fears, and ostracization of HIV/AIDS patients and Lippincott’s impact was wide-felt and humanizing.

In fact, in 1990, when Trudeau illustrated Lippincott’s death due to AIDS complications, an obituary was written for the fictional character in the San Francisco Chronicle: “… Lippincott, an affable man who had attempted to cope with the devastating disease with a continual patter of gallows humor, dies quietly in his bed, the window open to a sunny day and a coveted C.D. of the Beach Boys ‘Wouldn’t It be Nice’ playing.”

In the 2000s, like so many other middle school girls, when I turned 10 or 11, I was handed the American Girl’s “Care and Keeping of You.” The book includes comic strip-esque graphics and informational panels about everything from menstrual health to acne. It revolutionized the conversations that were and, more importantly, weren’t happening around girl’s health and puberty.

To put it simply: “Girls didn’t seem to have the courage to ask their own mothers these questions, but they were sending them to faceless magazine staffers in Middleton, Wisconsin.” Since its publication in 1998, “The Care & Keeping of You” has sold 7 million copies and counting.

From cancer to STIs to AIDS to puberty, comics clearly do have a place in medicine.

In recent decades, there has been a push in American healthcare for the medical humanities — a holistic movement that advocates for the intersection of science and art in medicine and medical education. Keith Wailoo, an American historian and professor at Princeton University, writes about the need for medical humanities:

“… [P]rofessional and human crisis has spawned the search for meaning and introspection about life, illness, recovery, human suffering, the care of the body and spirit, and death. Medicine’s social dilemmas, its professional controversies, human health crises, social tensions over topics from AIDS to abortion and genetics, as well as the profession’s very identity and its claim to authority have catalyzed and fed a growing demand for answers about meaning.”

Among the serious tomes included in Duke’s collection is the following spread from Tessa Brunton’s autobiographical “Notes from a Sickbed,” illustrating the onset and progression of her chronic illness. As Brunton writes, “catharsis” seems to best embody Duke’s Graphic Medicine collection. Like so many other comic strips, “Notes from a Sickbed” is a “bottled panacea.” Brunton confronts her illness and grapples with her own “search for meaning,” depicting her reality with humor, earnestness, and dialogue bubbles.

All of this to say: comics continue to have a place in medicine.

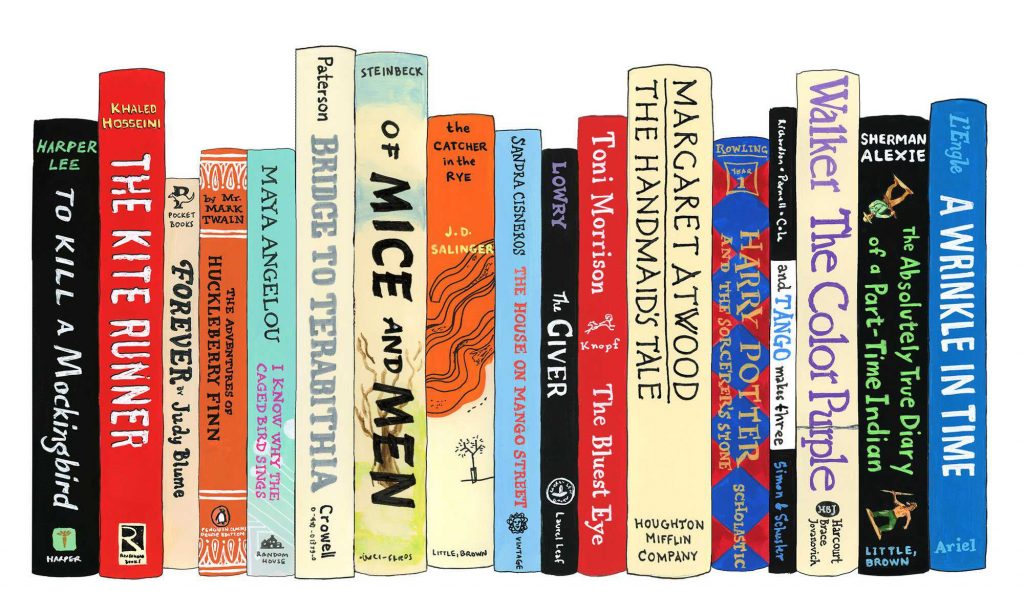

Here are a few texts in Duke’s Graphic Medicine Collection:

You can check out the entire Comic Medicine Collection here: https://mclibrary.duke.edu/about/blog/new-graphic-medicine-collection

Post by Alex Clifford, Class of 2024