DURHAM, N.C. — The barriers to minority students in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) don’t go away once they’ve finished school and landed a job, studies show. But one nationwide initiative aims to level the playing field once they get there.

With support from a 3-year, $500,0000 grant from the National Science Foundation, assistant professors and postdoctoral fellows who come from underrepresented minorities are encouraged to apply by May 5 for a free grant writing workshop to be held June 22-24 in Washington, D.C..

It’s no secret that STEM has a diversity problem. In 2015, African-Americans and Latinos made up 29 percent of the U.S. workforce, but only 11 percent of scientists and engineers.

A study published in the journal Science in 2011 revealed that minority scientists also were less likely to win grants from the National Institutes of Health, the largest source of research funding to universities.

Based on an analysis of 83,000 grant applications from 2000 to 2006, the study authors found that applications from black researchers were 13 percent less likely to succeed than applications from their white peers. Applications from Asian and Hispanic scientists were 5 and 3 percent less likely to be awarded, respectively.

Even when the study authors made sure they were comparing applicants with similar educational backgrounds, training, employers and publication records, the funding gap persisted — particularly for African-Americans.

Competition for federal research dollars is already tough. But white scientists won 29 percent of the time, and black scientists succeeded only 16 percent of the time.

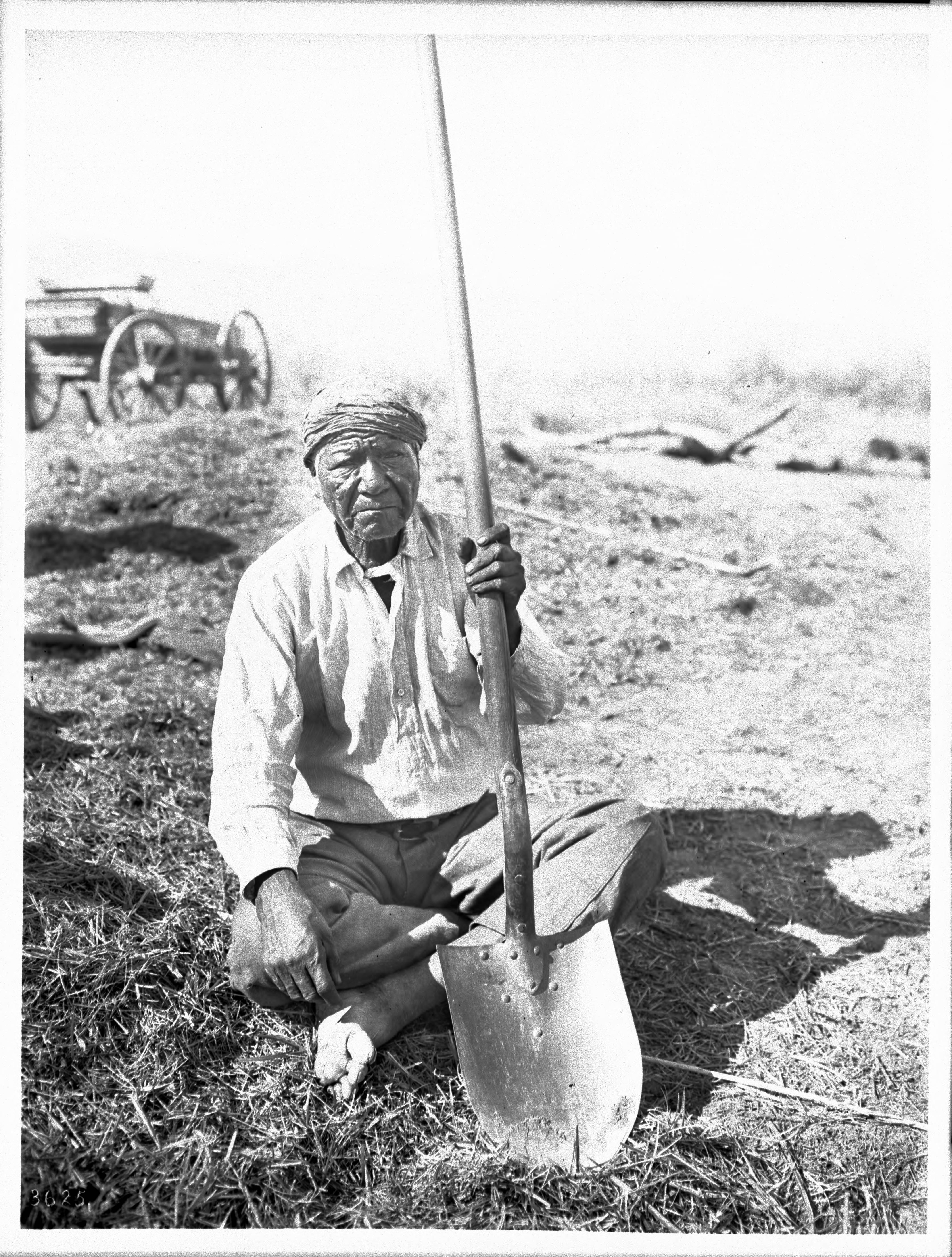

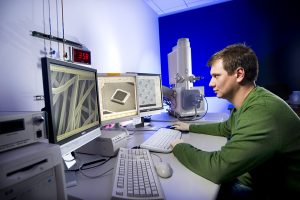

Pennsylvania State University chemistry professor Squire Booker is co-principal investigator of a $500,000 initiative funded by the National Science Foundation to help underrepresented minority scientists write winning research grants.

“That report sent a shock wave through the scientific community,” said Squire Booker, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and chemistry professor at Pennsylvania State University. Speaking last week in the Nanaline H. Duke building on Duke’s Research Drive, Booker outlined a mentoring initiative that aims to close the gap.

In 2013, Booker and colleagues on the Minority Affairs Committee of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology decided to host a workshop to demystify the grant application process and help minority scientists write winning grants.

Grant success is key to making it in academia. Even at universities that don’t make funding a formal requirement for tenure and promotion, research is expensive. Outside funding is often required to keep a lab going, and research productivity — generating data and publishing results — is critical.

To insure underrepresented minorities have every chance to compete for increasingly tight federal research dollars, Booker and colleagues developed the Interactive Mentoring Activities for Grantsmanship Enhancement program, known as IMAGE. Program officers from NIH and NSF offer tips on navigating the funding process, crafting a successful proposal, decoding reviews and revising and resubmitting. The organizers also stage a mock review panel, and participants receive real-time, constructive feedback on potential research proposals.

Participants include researchers in biology, biophysics, biochemistry and molecular biology. More than half of the program’s 130 alumni have been awarded NSF or NIH grants since the workshop series started in 2013.

Booker anticipates this year’s program will include more postdoctoral fellows. “Now we’re trying to expand the program to intervene at an earlier stage,” Booker said.

To apply for the 2017 workshop visit http://www.asbmb.org/grantwriting/. The application deadline is May 5.

Post by Robin Smith

Guest Post by Amanda Cox, PhD candidate in biology

Guest Post by Amanda Cox, PhD candidate in biology

Guest post by Ariana Eily , PhD Candidate in Biology, shown sharing her floating ferns at left.

Guest post by Ariana Eily , PhD Candidate in Biology, shown sharing her floating ferns at left.

Guest Post by Kendra Zhong, North Carolina School of Science and Math, Class of 2017

Guest Post by Kendra Zhong, North Carolina School of Science and Math, Class of 2017

Guest post by Raechel Zeller, North Carolina School of Science and Math, Class of 2017

Guest post by Raechel Zeller, North Carolina School of Science and Math, Class of 2017