We are all born with defining physical characteristics. Whether it be piercing blue eyes or jet black hair, these traits distinguish us throughout our entire lives. However, there is something that all of our attributes have in common, a shared origin: genes.

Beyond dictating our individual features, genes instruct cells to create proteins that are essential for a variety of processes, from controlling muscle function to managing digestive systems. Despite their importance in the workings of our body, genes can also code for detrimental diseases, such as Huntington’s disease or Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

These types of diseases are exactly what Raluca Gordân, Ph.D. is battling through her research. She and her group are trying to figure out how to decode the non-coding genome, the DNA apart from protein-coding genes. They are deepening their understanding of the role non-coding areas of the genome play in the expression of the coding genes and the production of proteins.

Gordân, an associate professor in biostatistics and bioinformatics at Duke, said a majority of disease-causing genetic mutations derive from the genome outside of genes.

“That is a huge search space,” she says, chuckling. “Genes only make up about 2% of the genome. If we don’t understand what those non-coding regions are doing, it’s hard to make predictions about what the mutation in those regions would be doing and how to connect that to the development of a disease.”

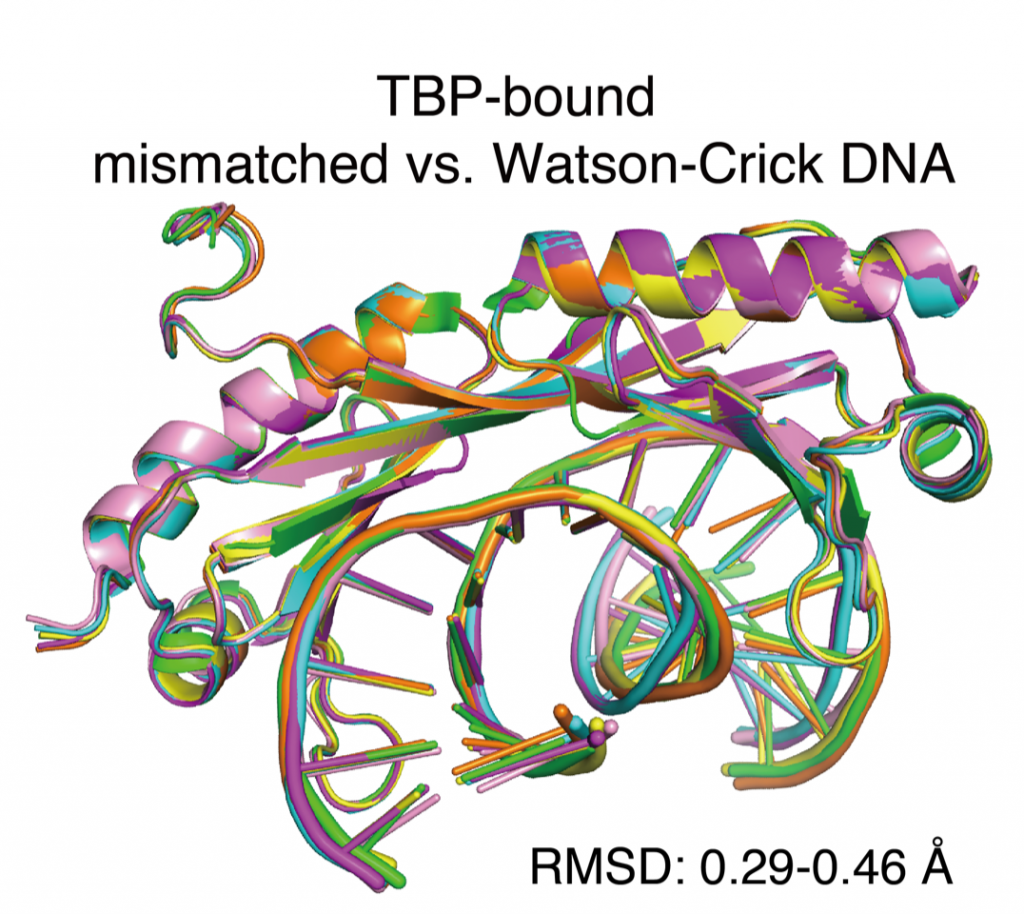

Gordân recently published a paper, entitled “DNA mismatches reveal conformational penalties in protein–DNA recognition,” which focuses on transcription factors and their exceptional ability to bind to mispaired DNA, misspellings that occur as DNA is copied. During regular replication, nucleotide bases (the building blocks of our DNA) are paired correctly, where adenine pairs with thymine and cytosine goes with guanine. However, when an error occurs during replication, mispairs start to appear, as adenine may pair with guanine instead.

“Normally, those are mistakes that get repaired by specific mismatch repair pathways but that repair might not happen if one of these transcription factors sits on the replication error and doesn’t allow the repair mechanism to see it,” Gordân explains. “Normally, one would expect the transcription factors not to bind to those errors. But we found that they can bind way better than their actual genomic targets.”

To expand on her computational discovery, Gordân is now following up with a study of transcription factor binding to mismatches in living cells, observing whether they adopt their usual role of regulating gene expression or contribute to the development of mutations.

Gordân’s research is a product of her passion and desire to make change. It also can be attributed to a series of realizations she made during college and inspirational mentors who guided her along the way.

While pursuing her undergraduate degree, Gordân was a purely computer science major, concentrating on cryptography. However, as she was nearing the end of her four years of college, she soon found herself yearning for the opportunity to do more. She began looking into machine learning applications and enrolled in a course based around genetic algorithms which she credits for launching her career path.

At that point, she attained what she describes as her “first taste of genetics” and her interest in bioinformatics was irrevocably piqued. Thereafter, Gordân applied for a PhD at Duke, where she worked with advisor Alex Hartemink investigating transcription factor proteins in regulatory genomics. At Duke, her work was primarily computational. But with her postdoctoral advisor Martha Bulyk of Harvard Medical School, Gordan was exposed to the more experimental aspects of biology.

Today, she recognizes these experiences as integral to her ongoing research, which requires her to frequently iterate between observational approaches and computational work.

Gordân is acclimating to the newly quarantined world. While she strives to continue her research, in the pandemic, it has changed her routine.

“I think what was affected a lot since the pandemic started is the fact that we don’t meet in person,” she says. “A lot of the quick progress was being made when we were in the same physical space and were able to get feedback immediately, with students learning about each other’s results in the lab, in real time. That was replaced with Zoom meetings, where students get to see the other students’ results mainly at lab meetings, weeks or months later. Those continuous discussions that were going on in the lab all the time. We’re missing that.”

Gordân offered some thoughtful parting advice to aspiring computational biologists, like me.

“I was trained as a computer scientist, so I wasn’t really sure about experimental work. But after actually doing the experimental work, I realized how much value there is in doing both,” she said. “You have to pick what you’re strongest at, either the computational or experimental part, but you should not be afraid of the other side.”

Guest Post by Akshra Paimagam, Class of 2021, NC School of Science and Math

By Anna Gotskind

By Anna Gotskind