What lies at the intersection of mathematics and biology? Freshly-minted math PhD Ruby Kim and her work on mathematically modeling human dopamine cycles.

Kim’s work has centered around her creation of a math model to predict how a person’s dopamine levels ebb and flow over the course of a day “to understand the general mechanics of how disruptions in the (biological) clock lead to disruptions in dopamine.”

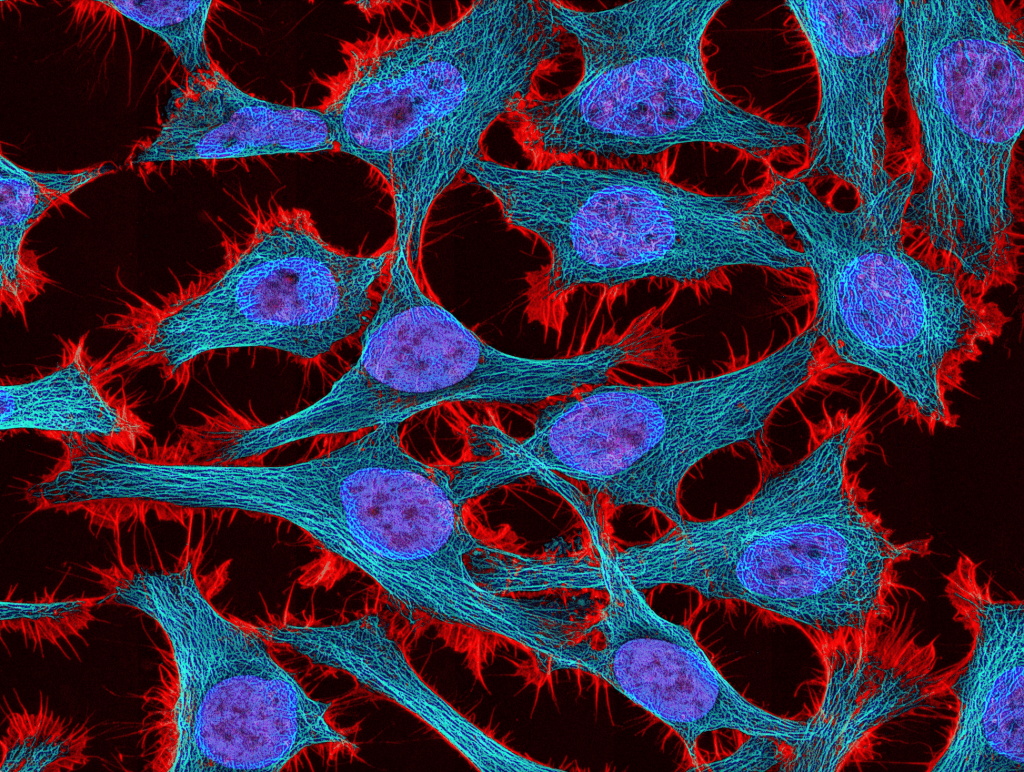

She said there is a pretty long history of mathematicians using differential equations to see how different clock genes and proteins change over the course of a day’s circadian cycle. Yet, no previous models have connected the circadian clock – controlled by the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus – to dopamine levels. And Kim tells me that work suggesting dopamine changes throughout the day are likely controlled by the internal circadian clock itself is “relatively new.”

The first step in Kim’s work was validating scientists’– or “experimentalists,” as Kim dubs them – hypotheses about dopamine and dopaminergic enzyme cycling.

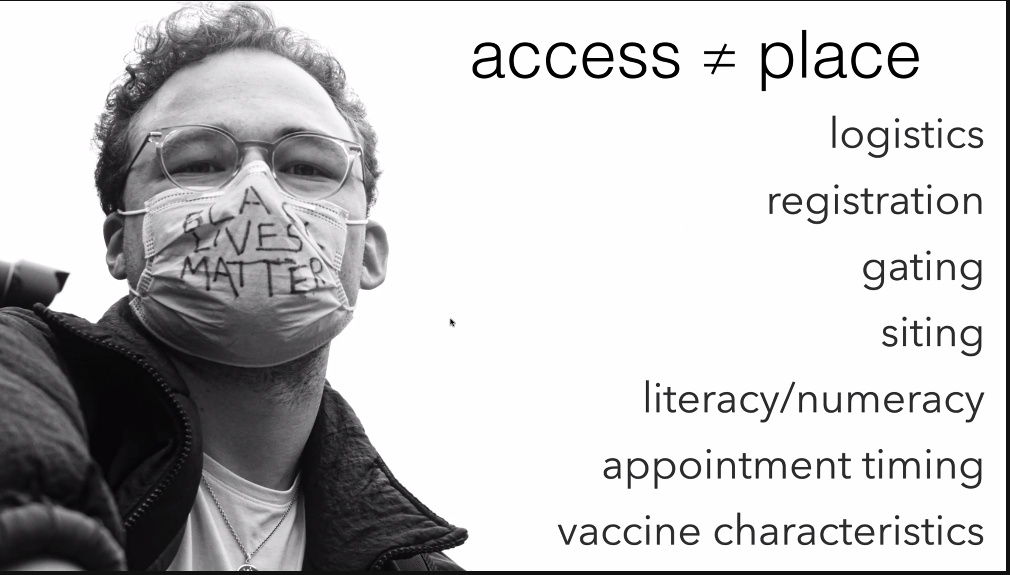

“But I’d like this work to help experimentalists go one step further and be able to test out hypotheses more easily.” For example, Kim says that her model has the potential to reveal other fascinating phenomena, such as how drug treatments or different genetic mutations may impact circadian rhythm or dopamine. This is thanks to the multifaceted layers of Kim’s model.

“From a mathematical perspective, the math model is very interesting. It has a lot of interesting dynamics,” she says. “Not only does it show nice, 24-hour rhythms, it shows both steady state behavior… but then also behavior that’s really wild – something called quasi-periodic behavior, where the internal clock is significantly different than the external 24-hour light-dark cycle.”

“This leads to oscillatory behavior that’s not periodic,” she says. These sorts of quasi-periodic behaviors have been observed in experiments and misunderstood, but they can be computed.

Kim emphasized the experimental and clinical implications of her work. Dopamine is involved in learning and motivation and is also linked a plethora of psychiatric conditions like Parkinson’s, ADHD, and schizophrenia. “Patients with these conditions often also experience circadian disruptions,” Kim says. “That’s a pretty big symptom.”

Kim began her academic career in her home state of California at Pomona College as a pre-med math major. “I had always been intrigued by human physiology. And math was one of the subjects I was also pretty drawn to. I just didn’t appreciate it much because throughout high school and the beginning of undergrad, I didn’t see any direct applications,” Kim told me.

The marriage of her love for math with her intrigue in biology actually began at Duke when Kim attended a mathematical biology workshop during the summer after her sophomore year. “I had never heard of math biology before that.”

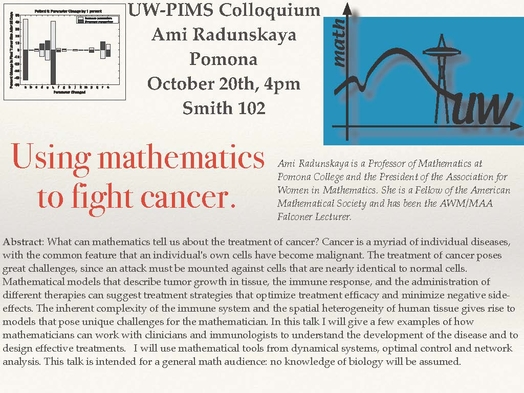

After working on a brief project to model sleep apnea in infants at the workshop, Kim returned to California and took up math modeling courses in her following semesters of undergrad. One of her professors, Ami E. Radunskaya, PhD, was extremely supportive and introduced Kim to a lot of “cool biological problems.” Kim went on to do research with Radunskaya, modeling tumor-immune interactions. This experience, Kim says, “kind of just threw me into academia.” The project gave way to an undergraduate thesis with Radunskaya that analyzed the long-term behavior of this tumor growth and treatment model.

Radunskaya then suggested that Kim pursue grad school. “I kind of applied on a whim,” Kim said, “It wasn’t something I had specifically imagined for myself.” Kim mentioned how no one from her home community had really ever gone to grad school and so it was not something she had ever “explicitly” thought about before.

In her search for a graduate program, Kim applied to math programs, as well as those that were interdisciplinary. “I ended up choosing Duke because I really liked my advisor,” Kim told me. While Kim’s advisor Michael Reed, PhD “does a lot of interesting math,” Kim wanted to work with him because math isn’t his focus – understanding “really complex biological systems using mathematical language is.”

“A lot of times you see people who do things at the intersection of math and biology that are more motivated from a mathematical standpoint … that’s just not what I’m interested in personally. I’m very interested in finding an interesting biological problem and then applying whatever mathematical tools I have.”

While at Duke, Kim was foundational to founding the university’s chapter of the Association for Women in Math (AWM). During her undergrad, Kim “had a really great experience with AWM,” finding both a community of women mathematicians and a network of women professors who were involved in the chapter.

At Duke, there wasn’t a chapter “but quite a few people who were interested in starting and being part of one.” This organization, which is open to people of any gender identity, heads mentorship programming that brings undergrads, grad students, postdocs, and professors together, organizes conferences, and contributes to their central focus of community building in math.

Outside of her research, Kim spends most of her free time taking care of foster pups, which she describes as “extremely rewarding but also very tiring.” Her most recent foster, a four-month-old puppy, eavesdropped on our interview as he took a nap.

This fall, Kim will begin a post-doc with the University of Michigan’s math department as she “wanted to keep studying circadian rhythms with faculty who are really great in that area.”

Post by Cydney Livingston, Class of 2022