Living in a 3-dimensional world, we can easily visualize objects in 2 and 3 dimensions. But as a mathematician, playing with only 3 dimensions is limiting, Dr. Henry Segerman laments. An Assistant Professor in Mathematics at Oklahoma State University, Segerman spoke to Duke students and faculty on visualizing 4-dimensional space as part of the PLUM lecture series on April 18.

What exactly is the 4th dimension?

Let’s break down spatial dimensions into what we know. We can describe a point in 2-dimensional space with two numbers x and y, visualizing an object in the xy plane, and a point in 3D space with 3 numbers in the xyz coordinate system.

Plotting three dimensions in the xyz coordinate system.

While the green right-angle markers are not actually 90 degrees, we are able to infer the 3-dimensional geometry as shown on a 2-dimensional screen.

Likewise, we can describe a point in 4-dimensional space with four numbers – x, y, z, and w – where the purple w-axis is at a right angle to the other regions; in other words, we can visualize 4 dimensions by squishing it down to three.

Plotting four dimensions in the xyzw coordinate system.

One commonly explored 4D object we can attempt to visualize is known as a hypercube. A hypercube is analogous to a cube in 3 dimensions, just as a cube is to a square.

How do we make a hypercube?

To create a 1D line, we take a point, make a copy, move the copied point parallely to some distance away, and then connect the two points with a line.

Similarly, a square can be formed by making a copy of a line and connecting them to add the second dimension.

So, to create a hypercube, we move identical 3D cubes parallel to each other, and then connect them with four lines, as depicted in the image below.

To create an n–dimensional cube, we take 2 copies of the (n−1)–dimensional cube and connecting corresponding corners.

Even with a 3D-printed model, trying to visualize the hypercube can get confusing.

How can we make a better picture of a hypercube? “You sort of cheat,” Dr. Segerman explained. One way to cheat is by casting shadows.

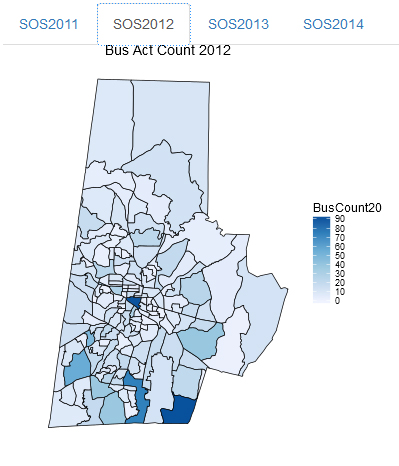

Parallel projection shadows, depicted in the figure below, are caused by rays of light falling at a right angle to the plane of the table. We can see that some of the edges of the shadow are parallel, which is also true of the physical object. However, some of the edges that collide in the 2D cast don’t actually collide in the 3D object, making the projection more complicated to map back to the 3D object.

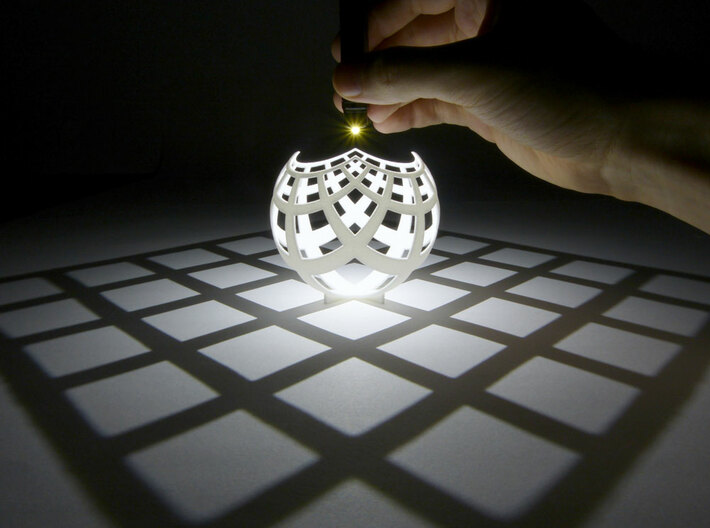

One way to cast shadows with no collisions is through stereographic projection as depicted below.

The stereographic projection is a mapping (function) that projects a sphere onto a plane. The projection is defined on the entire sphere, except the point at the top of the sphere.

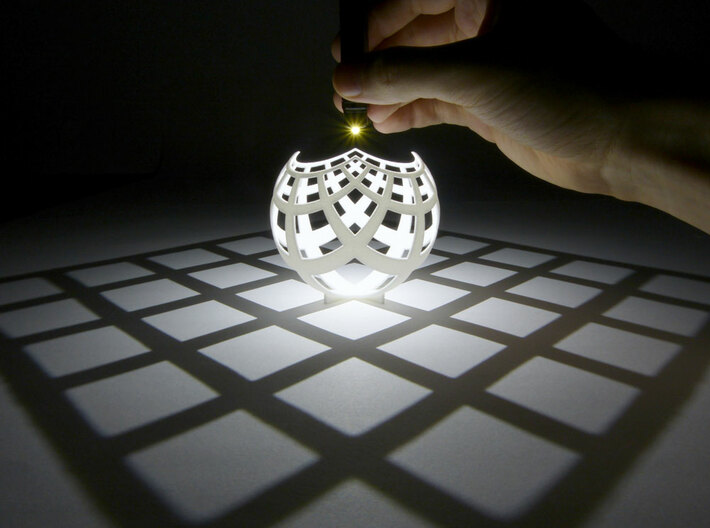

For the object below, the curves on the sphere cast shadows, mapping them to a straight line grid on the plane. With stereographic projection, each side of the 3D object maps to a different point on the plane so that we can view all sides of the original object.

Stereographic projection of a grid pattern onto the plane. 3D print the model at Duke’s Co-Lab!

Just as shadows of 3D objects are images formed on a 2D surface, our retina has only a 2D surface area to detect light entering the eye, so we actually see a 2D projection of our 3D world. Our minds are computationally able to reconstruct the 3D world around us by using previous experience and information from the 2D images such as light, shade, and parallax.

Projection of a 3D object on a 2D surface.

Projection of a 4D object on a 3D world

How can we visualize the 4-dimensional hypercube?

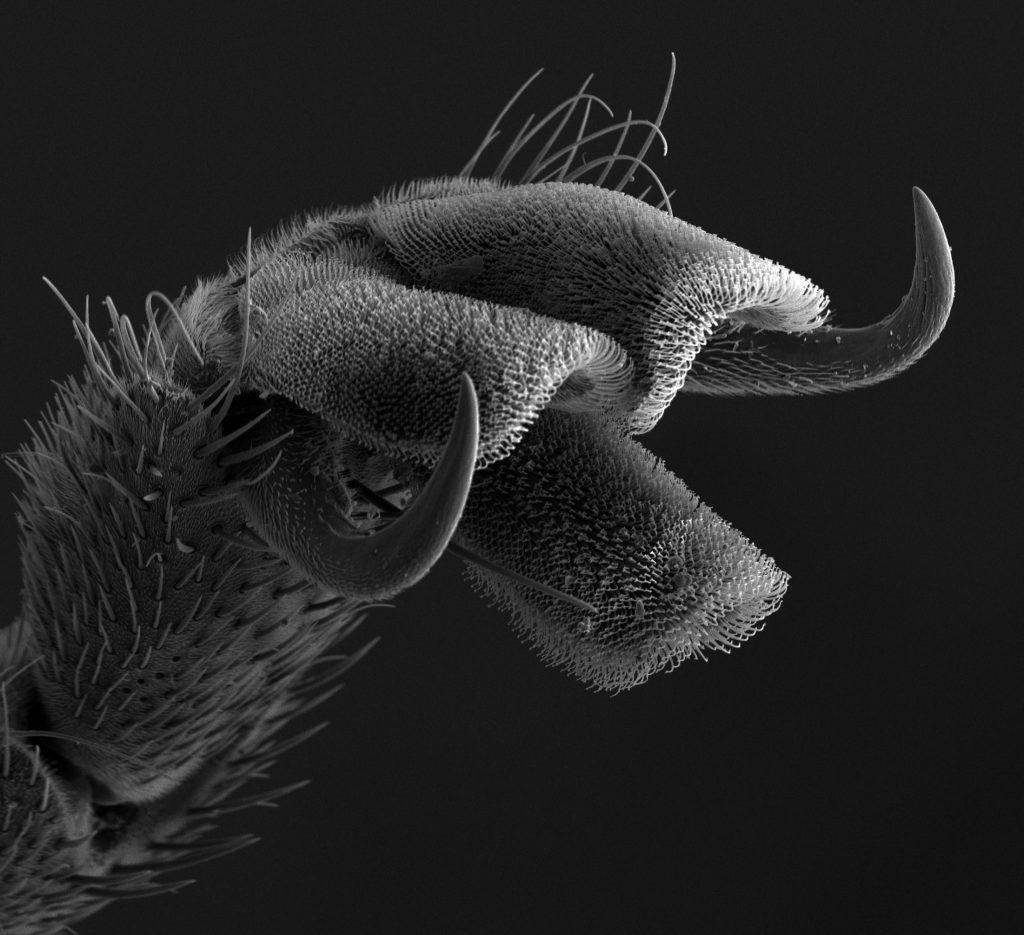

To use stereographic projection, we radially project the edges of a 3D cube (left of the image below) to the surface of a sphere to form a “beach ball cube” (right).

The faces of the cube radially projected onto the sphere.

Placing a point light source at the north pole of the bloated cube, we can obtain the projection onto a 2D plane as shown below.

Stereographic projection of the “beach ball cube” pattern to the plane. View the 3D model here.

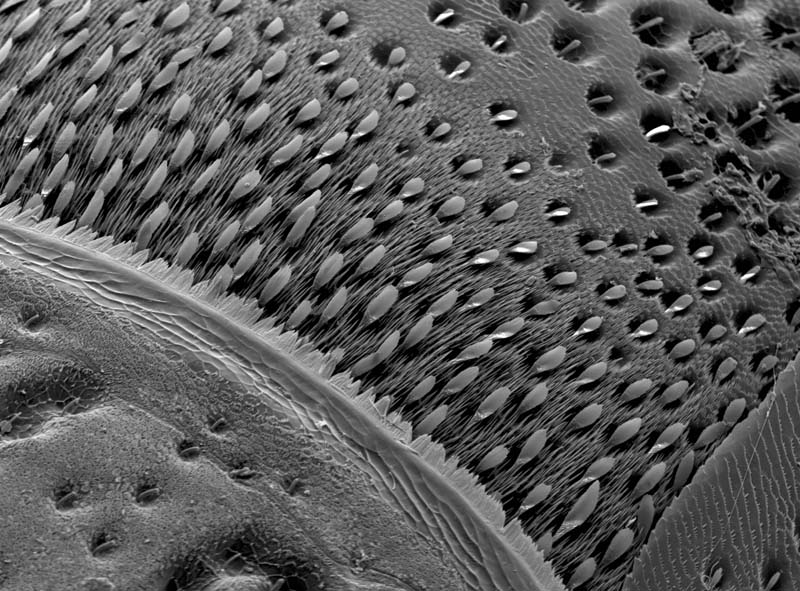

Applied to one dimension higher, we can theoretically blow a 4-dimensional shape up into a ball, and then place a light at the top of the object, and project the image down into 3 dimensions.

Left: 3D print of the stereographic projection of a “beach ball hypercube” to 3-dimensional space. Right: computer render of the same, including the 2-dimensional square faces.

Forming n–dimensional cubes from (n−1)–dimensional renderings.

Thus, the constructed 3D model of the “beach ball cube” shadow is the projection of the hypercube into 3-dimensional space. Here the 4-dimensional edges of the hypercube become distorted cubes instead of strips.

Just as the edges of the top object in the figure can be connected together by folding the squares through the 3rd dimension to form a cube, the edges of the bottom object can be connected through the 4th dimension

Why are we trying to understand things in 4 dimensions?

As far as we know, the space around us consists of only 3 dimensions. Mathematically, however, there is no reason to limit our understanding of higher-dimensional geometry and space to only 3, since there is nothing special about the number 3 that makes it the only possible number of dimensions space can have.

From a physics perspective, Einstein’s theory of Special Relativity suggests a connection between space and time, so the space-time continuum consists of 3 spatial dimensions and 1 temporal dimension. For example, consider a blooming flower. The flower’s position it not changing: it is not moving up or sideways. Yet, we can observe the transformation, which is proof that an additional dimension exists. Equating time with the 4th dimension is one example, but the 4th dimension can also be positional like the first 3. While it is possible to visualize space-time by examining snapshots of the flower with time as a constant, it is also useful to understand how space and time interrelate geometrically.

Explore more in the 4th dimension with Hypernom or Dr. Segerman’s book “Visualizing Mathematics with 3D Printing“!

https://youtu.be/Hg9-0dLDgJo

Post by Anika Radiya-Dixit.

Post by Meg Shieh

Post by Meg Shieh