One kilometer below the surface of Mount Ikeno in Japan lies Super-Kamiokande, the largest neutrino detector of its kind in the world. This 12-story, cylindrical chamber holds 50,000 tons of water and is lined with over 11,000 tubes that spot the bursts of light emitted when high-energy neutrinos collide with matter.

Nearly 20 years ago, experiments at Super-K and elsewhere revealed that neutrinos can oscillate or change “flavor,” a discovery which proved that the ghostly particles have mass and upended their role in the Standard Model of physics. Since then, Duke physicists Kate Scholberg and Chris Walter have used the massive detector to further explore the nature of these neutrino oscillations, seeking to pin down how and when they change their flavors and what this might mean for our understanding of physics.

Within the massive Super-Kamiokande neutrino experiment in Japan, researchers travel by boat to check individual photomultiplier tubes that detect bursts of light created when neutrinos interact with water. Credit: Kamioka Observatory, Institute for Cosmic Ray Research, The University of Tokyo.

On Wednesday, Scholberg and Walter, along with Duke neutrino physicist Phillip S. Barbeau, will tell the story of neutrino oscillations in a talk titled, “Hunting Ghosts, How a 50,000-ton underground detector revealed the changeable nature of the neutrino and altered our view of the Universe,” presented as part of the Natural sciences in the 21st century colloquium.

In preparation for the talk, Scholberg spoke with colloquium organizer Rotem Ben-Shachar about the nature of neutrinos, what makes them so hard to catch, and what they have teach us about the origins of matter in our universe.

What is a neutrino?

Neutrinos, sometimes known as “ghost particles,” are among the known “elementary” particles: unlike atoms, they are not made up of anything smaller. Neutrinos are special because they are neutral, meaning they have no electric charge, and they interact extremely weakly with matter. They also have very tiny masses: a neutrino has no more than about 1/500,000 the mass of an electron. Because of their tiny masses, neutrinos travel at speeds close to the speed of light. Neutrinos come in three “flavors”: electron, muon and tau.

Why are neutrinos so hard to catch?

Neutrinos only interact only via the weak force — this is one of the four known forces, the others being gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong force which holds atomic nuclei together. As you might guess from the name, the weak force is really feeble, and that means that neutrinos hardly ever interact with matter at all. Mostly they just pass right through things without leaving any trace. Once in a while, they do interact, leaving a charged particle that you can detect. In order to “catch” a neutrino — to detect the interaction — you need either a huge number of neutrinos, or an enormous detector, or preferably both. For example, Super-Kamiokande is gigantic, but we see only about ten high-energy neutrinos per day in the detector. On the surface of the Earth, cosmic radiation can easily swamp a signal this slight, so neutrino detectors are often built underground where they are shielded from cosmic radiation.

When we can catch a neutrino, what do we learn from it?

Duke scientists suspended inside the Super-K detector.

Particle physicists like us try to understand the basic nature of matter and energy: our goal is to learn what the universe is made of, and how its constituents interact with one another. We’re also interested in cosmology — the history and evolution of the entire universe. It’s essential to understand the fundamental physics in order to understand what happened after the Big Bang, and why the universe looks as it does today. For instance, nobody understands why the universe is made primarily of matter and not antimatter, which has properties very much like matter, but with opposite charge. The study of neutrinos can give insight into many questions like this one.

What specifically we learn with a neutrino detector depends on the source of neutrino, the type of neutrino, and how far the neutrinos travel. For instance, at Super-K we can detect neutrinos that come from collisions of cosmic rays, high energy particles from outer space, with the upper atmosphere. These neutrinos travel through the Earth: some of them go a short distance, and some of them travel all the way from the other side of the Earth. What we observe is that neutrinos change from one flavor to another as they travel — it turns out that this can only happen if neutrinos have mass.

The 2015 Nobel prize in physics was awarded for discovery of neutrino oscillations by the Super-Kamiokande and Sudbury Neutrino Observatory experiments. Why was this discovery so important?

The discovery that neutrinos oscillate as they travel — they change their flavor — told us that neutrinos have non-zero mass. This is a really fundamental piece of information. It completely changes the role neutrinos play in the Standard Model of particle physics, and in fact we still don’t know exactly how to fit neutrinos with mass into the picture; how to do this depends on whether neutrinos and antineutrinos are really the same particles or not.

Neutrino mass also matters for cosmology. Since neutrinos have mass, we know they make up some of the unknown “dark matter” of the Universe, but we also now know that neutrinos can only make up a small fraction of the dark matter. Exactly *how* the neutrinos oscillate also matters, as this depends on fundamental parameters of nature.

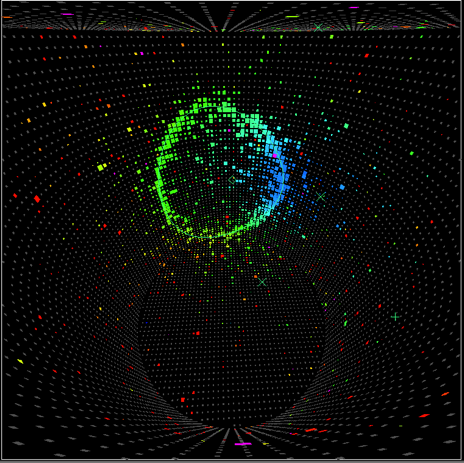

A 3-D display of a candidate electron-neutrino event in the Super-Kamiokande detector. Each of the colored dots represents a detector that was hit by the light created when the electron neutrino interacted with the detector.

How does your research build on the discovery of neutrino oscillations?

The discovery of oscillations in atmospheric and solar neutrinos by Super-K and SNO has now been confirmed by multiple other experiments, and we’ve made tremendous progress over the past 20 years in refining our understanding of neutrino oscillations. An experiment we are involved in at Duke, T2K (“Tokai to Kamioka”), sends a beam of high-energy neutrinos from an accelerator a distance of 300 km to Super-K. This experiment has discovered new oscillation properties of neutrinos and will continue to take data over the next several years.

But there are still big questions out there about neutrinos — we have three neutrinos, but we don’t know if we have two heavier ones and one light one, or two light ones and a heavy one, which matters for the big picture. We don’t know if oscillations of neutrinos and antineutrinos happen differently. We don’t know if neutrinos and antineutrinos are really the same particles. The answers to these questions may help us understand the origin of matter. A next-generation beam experiment, DUNE, will send a beam of neutrinos 1300 kilometers from Fermilab to South Dakota and may answer some of these questions — and if we are lucky, we’ll also catch a burst of neutrinos from a supernova.

The Natural sciences in the 21st century colloquium will be held Wednesday, April 13 at 4:30 PM in Duke’s Gross Hall, room 107.

Post by Kara Manke