Who will be the first company to secure an Emergency Use Authorization for a Covid-19 vaccine, and when? This question has circulated in the popular press for a few months and is at the forefront of many Americans’ minds with the upcoming presidential election on November 3rd.

Arti K. Rai (J.D.) moderated a dialogue between former FDA Commissioner and distinguished Professor of Cardiology, Robert Califf (M.D., M.A.C.C.), and Founder and Director of Scripps Research Translational Institute, Eric Topol (M.D.), in which the pair discussed emergency use authorization, public trust, and vaccines. The discussion was part of the Science & Society Initiative’s ongoing series of “Coronavirus Conversations.”

Arti Rai (J.D.)

Robert Califf (M.D., M.A.C.C.)

Eric Topol (M.D.)

Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) strengthen American public health protections by speeding the availability and use of medical countermeasures during public health emergencies. Dr. Califf explained that in addition to events like nuclear catastrophes that EUAs were designed to provide protections for, pandemics were also thought about in conceiving the emergency measure. “[The pandemic] is not a surprise,” Califf said, “We knew it was going to happen at some point.”

The panelists examined the possible use of EUAs for a Covid vaccine and monoclonal antibody treatments given the EUAs issued earlier this year for hydroxycholoroquine and convalescent plasma, the former of which was revoked due to proven risks. Both of these experimental treatments lacked sufficient evidence at the time the EUAs were approved.

Dr. Topol said that the EUA case for the antibodies treatment is a good one with growing evidence that suggests their effectiveness as a viable treatment measure. Dr. Califf concurred, saying that with 1,000 people predicted to die every day in the U.S. through the end of December, there’s a strong case for the FDA to exert its judgment. One issue with antibodies, however, is that they cannot be made in large quantities and are very expensive, meaning they would be inaccessible for many.

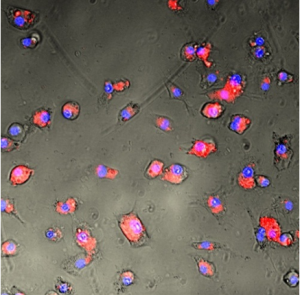

The question of EUA use for vaccines is less straightforward. Dr. Topol argued that though the protocols released by four drug companies, including Moderna and Pfizer, are pretty far along, “there is a very questionable ethical story here.” He continued, “How can we say it’s good enough to give to essential workers, healthcare works, high-risk individuals, but they won’t even give it to trial participants? They received placebo vaccines.” Across the board, the trials currently underway only include about 150 individuals.

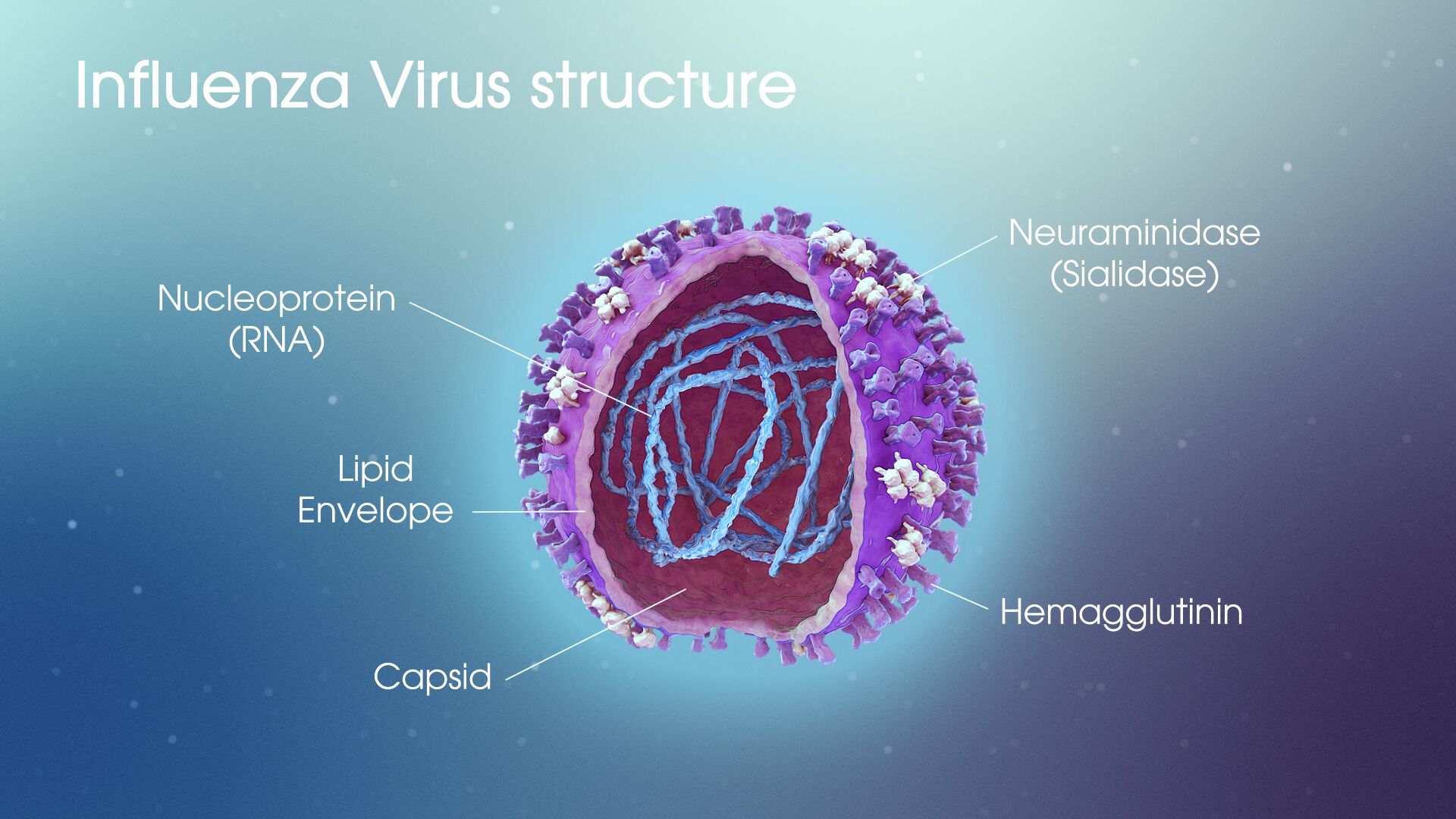

These initial trials are only the first hurdles to the production of a vaccine, according to both Califf and Topol. Dr. Califf pointed out that there will be issues of manufacturing and distributing, lots of concerns with post-market assessments, and how to determine which vaccines will be the best. Dr. Topol reinforced these ideas, suggesting that because no single company will be able to fill the vaccine demands, we need multiple vaccines to be successful. Further, Dr. Topol admitted his concern about the major extrapolations of data we will face, going from trials of 150 individuals to potential distribution numbers of vaccines reaching the hundreds of millions, if not billions of people.

And even once an initial round of vaccines is developed, Dr. Califf inserted the question, “What happens after people get vaccinated?” The simple truth is, the vaccination will probably not completely eradicate the virus, there could be late post-vaccination reactions, and the vaccine could potentially end up creating asymptomatic carriers. Both doctors agreed, masks and social distancing will be needed for at least the next year.

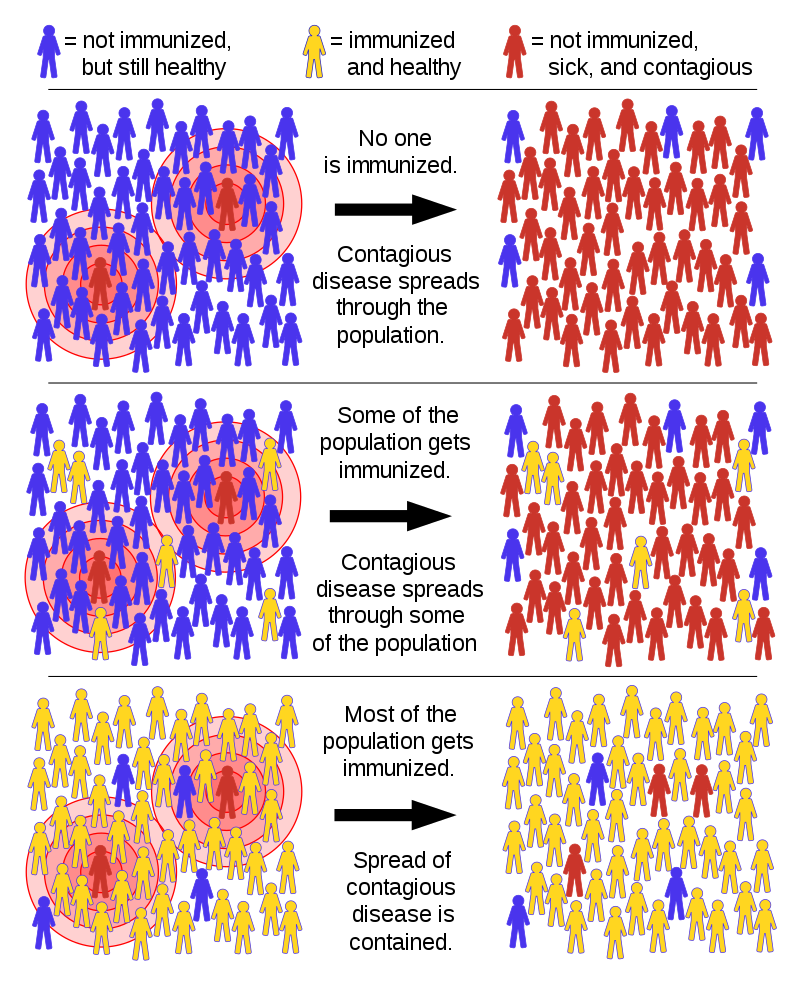

Public opinion and politics are also key players in vaccine debates and development. “The point of public trust is essential because if something happens with the first vaccine that gets out,” Dr. Topol said, “it’s going to be a real damaging blow to vaccine rollout.” Like mask-wearing, Topol suggested that vaccines are part of a larger social contract in which these sorts of preventative measures not only help oneself but those around them.

Rai pointed out that as tensions between the FDA and the U.S. department of Health and Human Services grow, as well as between the FDA and the Trump administration, we could face “doomsday” scenarios where the FDA is coerced into certain actions and their powers become limited. However, new FDA guidelines for vaccine development have extended the potential timeline for a Covid vaccine, meaning that the chances of a EUA being issued before the election and being utilized as a political tool for Trump’s reelection are quite unlikely at this point.

Dr. Califf closed by emphasizing the need for solidarity among the biomedical community as influential to the success or failure of potential vaccines and public trust. Dr. Topol offered that we “need education, government that supports science, and need to get [support from] people of all diverse backgrounds to get [the public] to buy in.”

While Dr. Topol maintained a more skeptical and sometimes grim tone, Dr. Califf said that though he’s worried about “everything,” he’s “preparing for the worst but hoping for the best.”

It seems that as many people grow both accustomed to and tired of our new normal, most of us are caught somewhere in the middle of these outlooks.

Post by Cydney Livingston

Post by Anne Littlewood

Post by Anne Littlewood

Post by Lydia Goff

Post by Lydia Goff