By Anika Radiya-Dixit

Have you ever been labeled an out-of-control teenager? A risky driver? An impulsive troublemaker? Here’s the bad news: That’s partially correct. The good news? It’s not your fault: blame the brain.

On November 18, the department of Psychology and Neuroscience introduced students to “The Origins of Heightened Risk Behavior in Adolescence.” The presenter, Dustin Albert, is a PhD research scientist at the Center for Child and Family Policy here at Duke University, who is interested in cognitive neuroscience, problem behaviors, and peer influence.

Researchers have identified the stage of adolescence as the peak time of health and performance, but at the same time, they noticed a jump in morbidity and mortality as children approached teen years, as seen in the graphs below. Specifically, adolescents show increased rates of risky behavior, alcohol use, homicide, suicide, and sexually transmitted diseases. However, as Allen tells the audience, “These are only the consequences.” In other words, what teenagers are stereotypically ridiculed for is actually the result of something else. If that’s the case, then what are the causes?

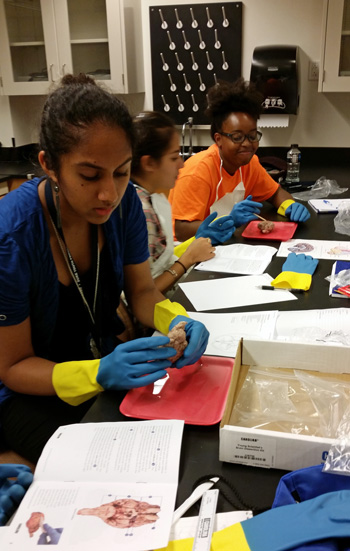

Professor Albert explaining the spike in risky behavior during teenage years.

Psychologically speaking, researchers believed that these behaviors are caused by a lack of rational decision, perhaps because adolescents “are unable to see their own vulnerability” to the outcomes, meaning that teens are apparently inept at identifying consequences to their actions. However, the studies they took demonstrated that adolescents are not only able to see their own vulnerability, but are also able to intelligently evaluate costs and effects to a certain decision. If teenagers are so smart, then what is actually causing this “risky behavior”?

One important reason Professor Albert discussed is brain activity and maturation before, during, and after adolescence. As a child ages from early to middle adolescence, fast maturation of incentive processing circuitry drives sensation seeking – in other words, the willingness to take risks in order to gain a reward increases as the child approaches teen years. In the brain, this occurs due to increased dopamine availability in reward paths as well as heightened sensitivity to monetary and social reward cues. In one interesting study, adolescents were instructed to press a button only when they saw an angry face. However, the researchers noticed that when the teens saw a happy face, they had a “particularly difficult time restraining themselves” to not press the button. Essentially, the happy-angry face study demonstrates that adolescents have more struggle in restraining themselves against impulsive actions, which often translates into responses during driving, alcohol use, and the other aforementioned risky behaviors.

Later in their life, there is a slower maturation of cognitive control circuitry that leaves a window of imbalance in the teen’s life. In the brain, this period is noted by thinning of gray matter and increasingly efficient cortical activation during inhibition tasks. In other words, older people “use smaller parts of [their] cortex to stop inappropriate responses.” Essentially, due to the way the physical and hormonal brain matures, adolescents are more prone to impulsive behavior. The take away: it’s not your fault.

Another influence on teens’ risky behavior is called the peer presence effect, commonly known as “peer pressure.” Based on arrest records, “adolescents, but not adults, [are] riskier in the presence of peers,” pointing out that the percentage of co-offenders arrested for the top eight crimes decreased with age after teenage years (Gardner & Steinberg, 2005). Perhaps the need to “establish their status,” Albert speculated, decreases with age as they gain more experience about living in the real world.

The test to evaluate the result of peer presence simulates the effect of teens taking a driving exam when in the car alone as compared to when with peers. In terms of peer influence, the study shows that adolescents ran more intersections when sitting with a peer than when sitting alone. In terms of risky behavior compared with adults, adolescents when watched by peers showed over 20% increase in risky behavior of running through intersections, as opposed to the 5-10% increase seen for adults in peer presence. Albert partially attributed this effect to the fact that “teens driving the first time could assess the probability of crashing less than adults do,” but he doesn’t have specific evidence for this claim.

While Albert claimed that the study was valid because the adolescents participating were made aware of the outcome of driving recklessly – damage to the car, injury, time it would take to get a new car, insurance problems – I believe that the study should have taken into account the fact that the teens may have subconsciously known the simulated driving test wasn’t real – viewing it as a mere video game – and so may have succumbed more into peer pressure as the true fear of dying in a crash would not have been present.

Albert ended his talk by giving one last piece of advice to people working with teens: It’s “not enough to [simply] increase their knowledge,” but rather to “understand and work towards developing impulse control and reward sensitivity.”

Below are some of the thought-provoking questions raised by audience members during the Q&A session:

Q: What would be the result of peer presence effect for same-sex peers as compared to peers of the opposite sex?

A: While Albert admitted that this particular situation has not been tested yet, he believes it may be based on personal perceptions of what the peer thinks, and what the opposite person likes.

Q: What would be the result of risky behavior for the simulated driving test if the participant’s parent(s) and peer(s) were both present in the car?

A: On one hand, the participant might drive more carefully due to the presence of an authoritative figure. However, if the participant opinionates the peer as a stronger influence, he / she would effectively neutralize the effect the parent has and drive more recklessly. Other audience members claimed that they would drive more cautiously irrespective of who was sitting with them in the car because they are aware there is another life at stake for every decision they made behind the wheel. “It would be interesting to see the [results of the study] based on this internal conflict,” the audience member who posed this question said. Overall, Albert said the results would be primarily influenced by the type of person participating – whether they would “take the small amount of money or be willing to wait for the big amount” in front of peers – that would determine whether the parent or peer becomes a stronger influence in risky behavior.

Q: How could someone going into education help keep high school students away from risky behaviors?

A: Albert noted that these behaviors are more the result of personal experience rather than something that can be quickly taught. In a school setting, teachers could introduce the practice of challenging situations to help the kids acting ‘in-the-moment’ recognize and understand “changes in their own thought patterns for decision making,” but simply giving them a “lesson in health class is not necessarily going to translate into the Friday night situation.”

If you are interested in these type of topics, Professor Albert is teaching PUBPOL 241: METHODS SOCIAL POLICY RESEARCH this Spring (2015).

More details about the presenter can be read at: http://fds.duke.edu/db/Sanford/ccfp/william.albert