LinkedIn, the social media platform for career-related connections, has a huge problem. The company has a grand vision of making the world economy more efficient at matching workers and jobs by completely mapping the data its 364 million users have posted about their skills, work history, education and professional networks.

But that turns out to be a much more gnarly problem than anyone expected. So, the company has done the Internet-age thing and crowd-sourced it.

Two Duke teams are among 11 selected last month from hundreds of proposals to participate in the company’s economic graph challenge. Selection means each team gets $25,000 (not quite enough for one grad student), a special secure LinkedIn laptop granting access to “a monitored sandbox environment,” and a mentor within the company who will stay in regular contact.

They’re supposed to deliver results in a year.

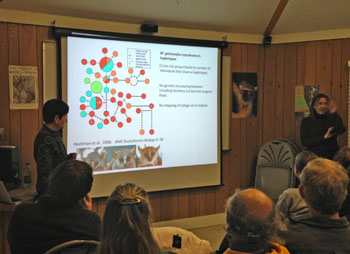

A Duke team lead by statistics professor David Dunson seeks to draw a richly detailed 3-D map of the network, making connections by education, skill set, employers and so on. “That’s incredibly difficult,” Dunson said. “With hundreds of millions of users, even a simple network would have 100 million-squared nodes, which is absurd.” His team hopes to develop algorithms to break the computation problems into manageable chunks.

This project, called “Find and change your position in a virtual professional world,” also includes statistics PhD student Joseph Futoma and Yan Shang, a PhD student in operations management at the Fuqua School of Business.

The other team is trying to pair whole-language analysis of user profiles with a three-dimensional map of a user’s network to speed job connections.

“We could have an awesome algorithm, but if it takes the age of the universe to run: ‘Hey, we’ve got a job for you — if you’re still alive!’” said Katherine Heller, an assistant professor of statistics and computer science. Her team, “Text Mining on Dynamic Graphs” also includes David Banks, professor of the practice in statistical science, and statistics PhD student Sayan Patra.

What the Duke teams are most excited about is the chance to tackle real-world data on a scale that few academics ever get a chance to work with. “These data are super-more interesting,” Dunson said. “It’s amazing to think of all the different things you could do with it.” If the academic teams come up with good solutions, they might be tools that could be used on other big-data problems, he added.

Even if the problems aren’t solved, LinkedIn’s contest has also built a good connection to the Duke campus, Heller notes. “It gives them access to seeing what’s going on in the department and possibly meeting some of the students,” she said.

And that’s the sort of thing that might lead to some new career connections.

-By Karl Leif Bates