Conversations on and actions toward making American medicine less racist continue to grow. At Duke, that includes looking at our own history as a hospital and medical center serving a diverse community.

In a Sept. 22 virtual conversation, Duke physicians Damon Tweedy M.D., Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, and Jeffrey Baker M.D., Ph.D., Director of the Trent Center for Bioethics, Humanities, and History of Medicine, spoke about the history of Duke’s legacies of race and memory. (Watch the presentation here.)

Dr. Damon Tweedy

Dr. Jeffrey Baker

The career of Dr. Baker, who is a professor of both pediatrics and history, has taken him around the globe, right back to his hometown of Durham –where he said he has found the most interesting story of all.

After becoming Director for the Trent Center in 2016, he was approached with “hunger” by Durham natives to know their hometown’s story. Through oral and archival sources, Dr. Baker has broached Duke hospital’s history with humility in hopes of uncovering and contextualizing the historical roles of race in Duke medicine and Durham.

Dr. Tweedy, author of Black Man in a White Coat, attended Duke for medical school in the 1990s. He was warned that it was a plantation and an institution built on tobacco and slave money.

Though Dr. Baker proposed that in many ways the hospital structure often reflects plantation hierarchies in which there is racialization of who holds what jobs and power, he said Duke’s endowment money actually came from technological progress within tobacco production rather than slavery or plantations directly.

The Duke family’s vision for the hospital was quite different from actual outcomes in practice, Dr. Baker said. The Dukes were considered racial progressives in their time and the endowment they provided to launch the Duke Medical School and Hospital in 1930 was meant to improve health and education in North Carolina and train primary care doctors for the state.

“However,” Dr. Baker said, “there were two realities: Jim Crow and the Great Depression.”

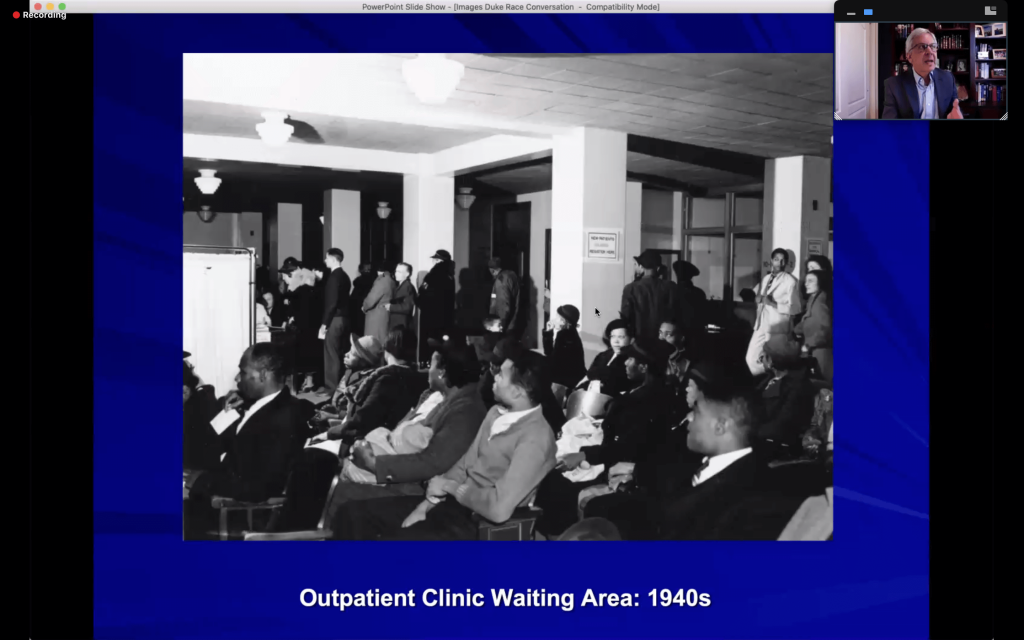

During the era of Jim Crow segregation, Duke’s primary care doctors were all white, and nearly all male. Though the hospital cared for both Black and white patients, they were segregated by race. Black patients had separate wards, and waiting areas for pediatric care were separated racially by days of the week. Waiting areas for adult patients functioned without appointments, but only white people were seen before noon. It’s likely that the care granted to white people in the first half of the day was superior to that of Black people receiving care at 4 pm or told to return the next day, he said.

The Great Depression also generated a diversion from plans in the 1940s. When the Duke Hospital came close to bankruptcy, it chose to open private clinics on the side for revenue – which had an unintended consequence. The clinics brought a lot of money into Duke, Dr. Baker said, but it also reinforced distinctions between those who could pay for treatment and those who couldn’t. Over time, the disparities expanded with shifts towards hospital beds for insured and private patients.

In one terrible example, Maltheus “Sunny” Avery, a North Carolina A & T graduate who got into a car wreck in Burlington, NC in 1950, was diagnosed with an epidermal hematoma — a clot near his brain — and sent to Duke for emergency brain surgery. But he was refused treatment due to inadequate room in the “colored” ward.

Avery was redirected to Lincoln Hospital, Durham’s Black hospital, where he died shortly after admission. Though Dr. Baker said this story quickly faded from white memory, it is something that has retained severe importance in the popular memory of Black Durhamites. This narrative is also often conflated with a similar story about Dr. Charles Drew, the Black inventor of blood banking, who died despite attempts at rescue at a white hospital in Alamance, NC. He is often misremembered as having died from the refusal of care in a racially divided South, even though he was not.

Duke’s first Black medical student, Delano “Dale” Meriwether, arrived the same year the hospital began desegregation, 1963, and he was the first Black M.D. in 1967. Meriwether was the only Black medical student for four years before other brave pioneers joined the school.

Dr. Tweedy reflected on his own medical school experiences at Duke during clinical rotations just a little more than 20 years ago.

“I was asked to help suture a deep gash on a Black patient’s forehead,” he said, “The patient asked if we were experimenting on him since I was still a student.” In the private clinics, he once “couldn’t go anywhere near” a white patent with a minor lesion on their arm, let alone suture that patient.

Dr. Baker said there are two narratives surrounding Duke Hospital’s desegregation. One assumes that desegregation was quick and easy and uneventful, while the other proposes that systems of racial segregation were simply transformed rather than eradicated. The latter narrative better applies to the public and private clinics that had become nearly completely racialized over time, Baker said.

Even though segregation was no longer legal, Black patients received care from less experienced medical residents in the public clinics, while white patients received care from attending physicians in the nicer, private environments.

Dr. Baker said that Duke has a complicated relationship with the community of Durham. He said the merger of Durham Regional Hospital with Duke Health in the late 1990s tapped into some long-term tensions and distrust between Duke and other medical facilities of Durham.

Dr. Tweedy pointed out that Duke researchers always have trouble recruiting Black patients for clinical studies, despite the fact that Durham County is about half Black and Hispanic. There is some distrust to overcome, but a diverse patient population is essential to creating robust study data that ensures that treatments will work for everyone, he said.

Medical professionals “need more than just science,” Baker concluded. He said that being trained as scientists often inclines doctors to think that they are above the larger contexts and histories they exist within, and that they can somehow remain objective.

“We have come out of specific stories and backgrounds,” Dr. Baker said. “[When we treat patients], we have to think about what story we are walking into.”

“We all carry our bags of ‘stuff'” that complicate patient prognosis and care, Dr. Tweedy concurred.

As Ann Brown (M.D., M.H.S), Vice Dean for Faculty, stated at the beginning of the conversation, “In order to move forward, we must understand where we come from.”

This is true of our nation as a whole, and Duke is certainly no exception.

Post by Cydney Livingston