Science fiction may seem an unlikely source for research inspiration. But for Duke University Provost Alec Gallimore, it has been just that: inspiration for a career’s worth of electric propulsion research.

Gallimore said it was stories from science fiction authors like Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov that piqued his interests for fusion and other advanced propulsion technologies at a young age. It is an interest that led him to pursue studies in aerospace engineering with a focus in plasma physics at Princeton University and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

He channeled those interests into the Plasmadynamics and Electric Propulsion Laboratory (PEPL) he founded as a professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Michigan. Focused on the development and testing of more efficient and powerful electric thrusters for spacecraft, the lab has long been at the forefront of electric propulsion research.

High thrust, high efficiency electric propulsion systems are poised to transform space exploration. They are viable replacements for the inefficient, yet flight-proven chemical thrusters typically used on spacecraft. This is because the electric thrusters can operate over longer periods of time, providing sustained thrust that allows spacecraft to travel the solar system in record time. Electric propulsion systems are slated for use on countless future spacecraft, from the Gateway lunar space station to Mars orbiters.

Gallimore said he is proudest of the X3 Nested Channel Hall Thruster developed at PEPL. Weighing just a tenth the size of an SUV at 230 kg, the X3 is one of the largest, most powerful electric thrusters the lab has developed. It consists of three nested chambers in which ionized gases are accelerated by electric fields, generating thrust highly efficiently. Most Hall-effect thrusters – the category of electric thruster to which the X3 belongs – contain only one chamber. The X3’s three separate chambers help it generate substantially more thrust. That means it can be used to propel heavier spacecraft destined for more distant locations in the solar system.

Gallimore sees this as just the beginning for electric propulsion. Miniaturized electric thrusters will also, according to him, become mainstays on smaller satellites, providing them with the propulsion capabilities they have long lacked. More important will be future research on novel propellant types for electric thrusters, specifically water. “Water is the answer,” Gallimore said.

“Water is all over the place in the solar system, and so you are able to develop an infrastructure where you can tank up as you need to with water as your propellant,” he explained. “It opens everything up in the solar system so that, by the second half of the century, you can have an amazing infrastructure throughout the inner part of the solar system with water as a propellant.”

Leading research advancements such as these comprised much of Gallimore’s work at PEPL, experience that has informed his work at Duke, where he became provost in July 2023. “Genius is 10% inspiration, 90% perspiration,” he said. Having a team of people fully committed to their research and a common mission was vital to him.

So was having a diversity of opinions. PEPL hosted researchers from varying disciplines such as applied physics and aerospace engineering, as well as diverse life experiences and identities. That promoted a culture of “mutual respect” in “intangible ways” that drove innovation and staved off “group think,” he said.

That philosophy of thoughtful discussion and collaboration is one Gallimore has taken to Duke, informing the Office of the Provost’s efforts to advance academic excellence and improve campus community.

Whether as an electric propulsion researcher developing the thrusters that will take humans to Mars or as Duke University Provost, working to invigorate the school community, Gallimore has pushed boldly forward. In a future perhaps defined by advanced human space exploration and a more just world, we will no doubt have some small thanks to pay to Gallimore.

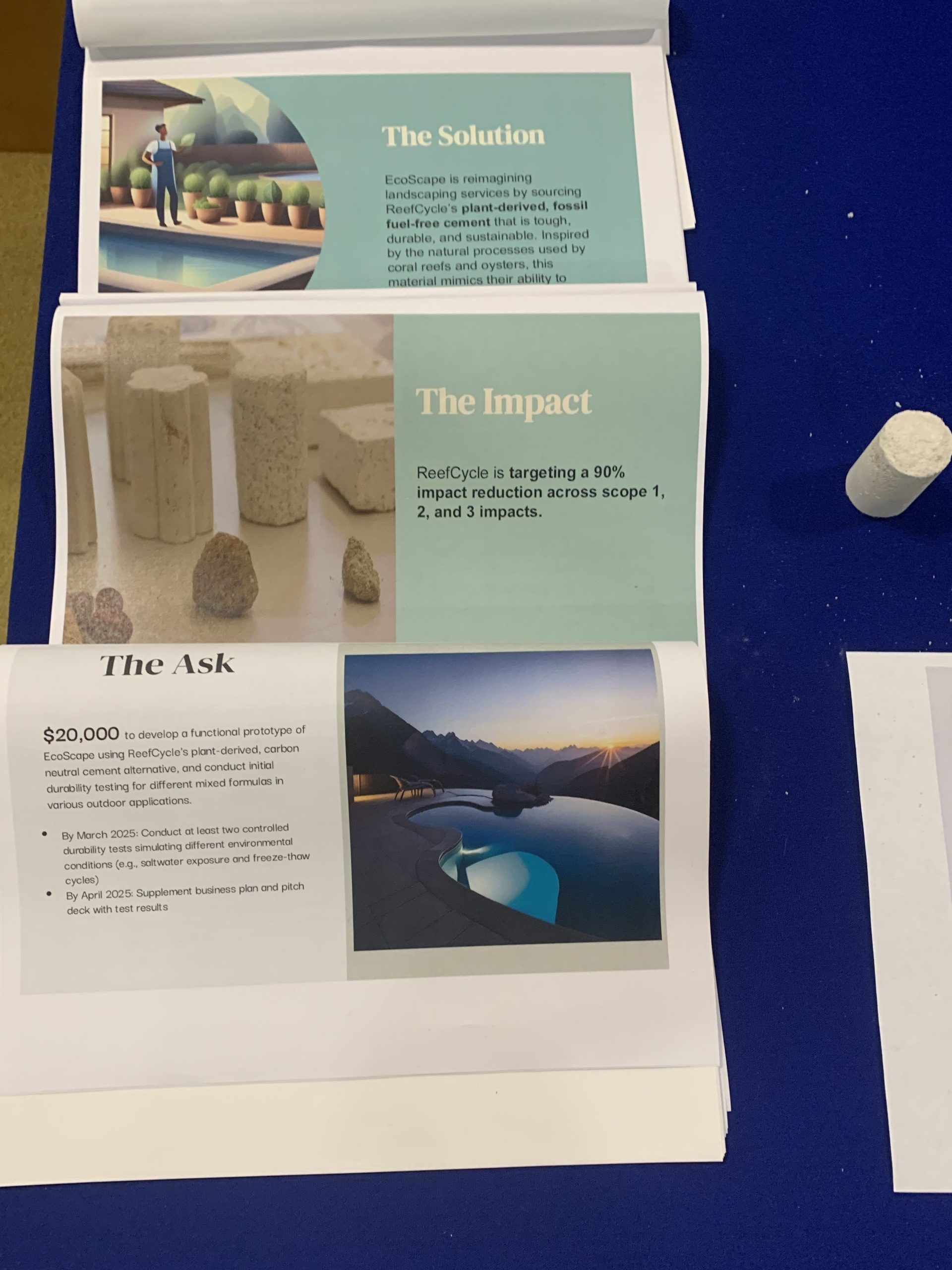

based and enzymatic, meaning it’s essentially grown using enzymes from beans. Testing in the New York Harbor yielded some promise: the cement appeared to resist corrosion, while becoming home for some oysters. The Design Climate team is now trying to bring it to more widespread use on land, while targeting up to a 90% reduction in carbon emissions

based and enzymatic, meaning it’s essentially grown using enzymes from beans. Testing in the New York Harbor yielded some promise: the cement appeared to resist corrosion, while becoming home for some oysters. The Design Climate team is now trying to bring it to more widespread use on land, while targeting up to a 90% reduction in carbon emissions