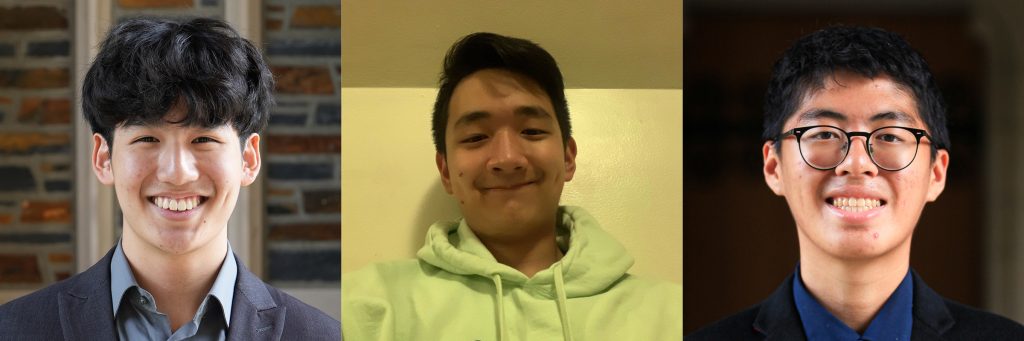

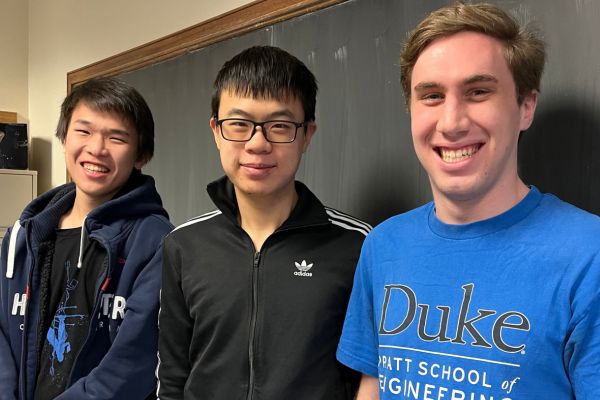

“Hi, my name is Stone. S-t-o-n-e.”

Since move-in day, I have repeated this introduction hundreds of times. Curiously, I received a lot of “that’s a cool name!” comments in response… enough times to make me pause and think about my name and the history behind it.

“Stone” has not always been a source of pride. Imagine the fun middle schoolers had with it: “ColdStone,” “Stone Cold,” “You Rock,” and other variations. And the name was supposed to be a refuge: my legal name, Shidong, has been so frequently mispronounced by teachers (typically on the first day of school) that I had been convinced that Stone would be a better choice.

The unfortunate nicknames aside, I found explaining the origin of “Stone” to be a hassle. After all, my legal name’s meaning had nothing to do with pebbles or other igneous creations. The Chinese character “shi” meant soldier and the character “dong” translated to scholarship. When I arrive here during some conversations, I find myself often disappointed that the profound meaning behind my name is often thought of in terms of rocks.

Why the lengthy introspection about a few letters? In my few weeks here at Duke, I realized that I am experiencing a rejuvenation in my identity, encouraged by “that’s a cool name!” comments. My name, who I am, what my interests are, and other factors are no longer restricted by previous limitations in the form of high school curriculum, club offerings, or social culture. I am interacting with much more diverse students who, like me, have long and winding life stories and are willing to share them with others.

In short, the personal biography I am about to share with you is dynamic. At Duke, my mission is to explore as much as possible, both in the classroom and beyond, doing things that I would have despised a few short years ago (going against upper class students’ advice on course selection is an egregious sin for young Stone). It is possible that in a semester or two, my academic and extracurricular interests will have shifted so radically that none of what I wrote below is still accurate. Maybe that is my most important trait right now: willingness to experiment and change my mind. This is what led me to this opportunity with the Research Blog and why what you are reading exists in the internet world.

Now onto the “traditional” introduction: I am Stone Yan, a first-year student pursuing Biomedical Engineering. I hail from Chicago, Illinois, where the weather is as unpredictable as Durham, but the humidity is never intolerable. I am interested in medicine as my career after graduation, and I hope to study some health policy courses here in addition to my Pratt curriculum. I would describe myself as hard-working, curious, and determined.

Outside of grinding academics, I love to play the piano, play badminton, follow the news, and hang out with friends. Running, drawing, and watching YouTube are also favorite pastimes. My most hated household chore is folding laundry… I can never fold the clothes neat enough. My deepest fear is someone dumping my washed and dried clothes on the ground after I forgot to run to the laundry room… Randolph friends, please do not do this to me.

Hopefully, there were some sentiments shared here that you echoed. My mission as a blogger with the Research Blog is to broadcast tidbits that we do not typically notice and call our attention to amazingness overshadowed by other amazingness (too much of this on campus!). My focus will probably be on the people that make Duke special to all of us: the faculty, staff, students, athletes, alumni, and community members that make us proud to be Blue Devils.

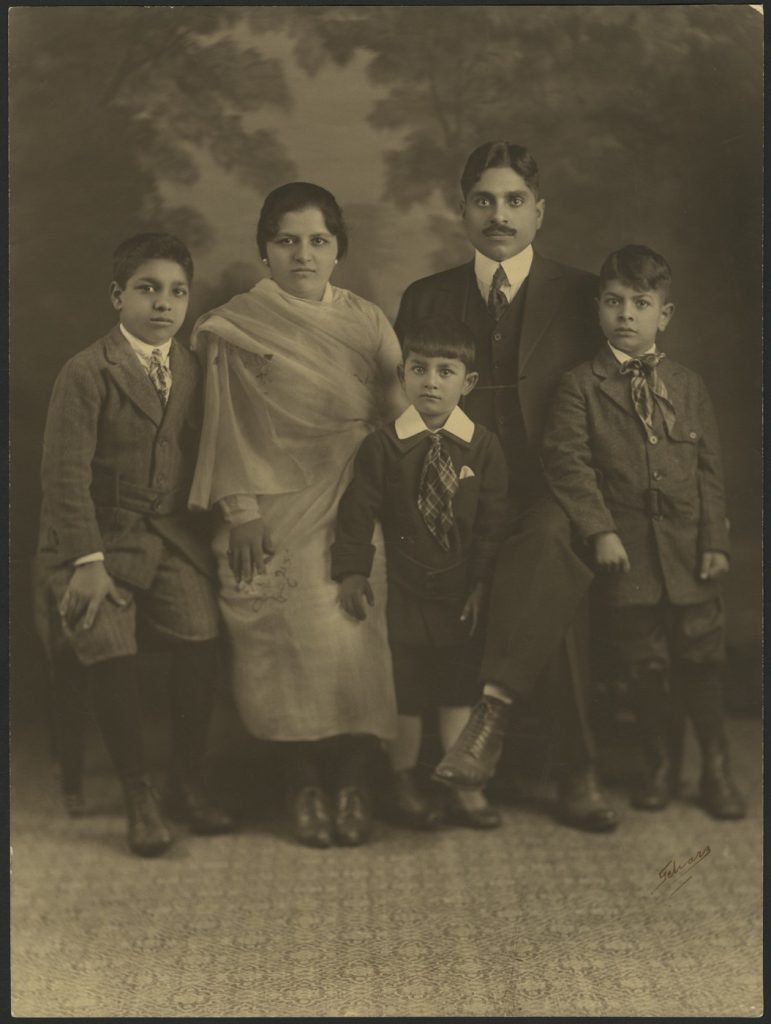

I cannot conclude without giving a shoutout to my parents. As an only child, I was remarkably close to them, and I cannot thank them enough for their boundless support.

Cheers to celebrating Duke’s rich community in future blogs!