How should we engage with books, songs, or other works of art created by artists, dead or alive, who have done bad things or hold morally problematic views?

The list of artists who have been accused of doing or saying disparaging, criminal, or morally reprehensible things is long. Paul Gauguin. Michael Jackson. Woody Allen. J.K. Rowling. Kanye West. Pablo Picasso. R. Kelly. Louis C.K. Bill Cosby. Many more.

It’s one thing to firmly condemn their actions and reject their beliefs. But what should we do with their art—as individuals and as institutions?

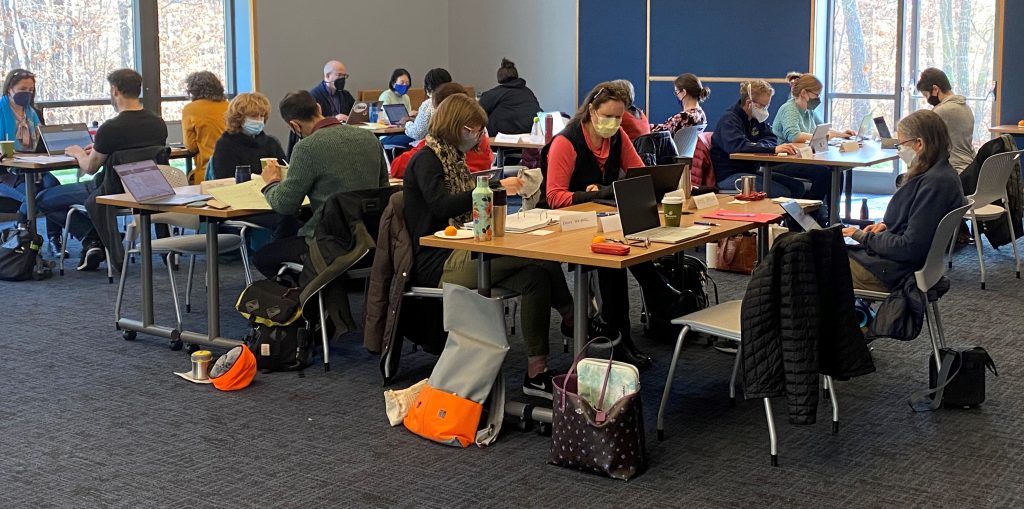

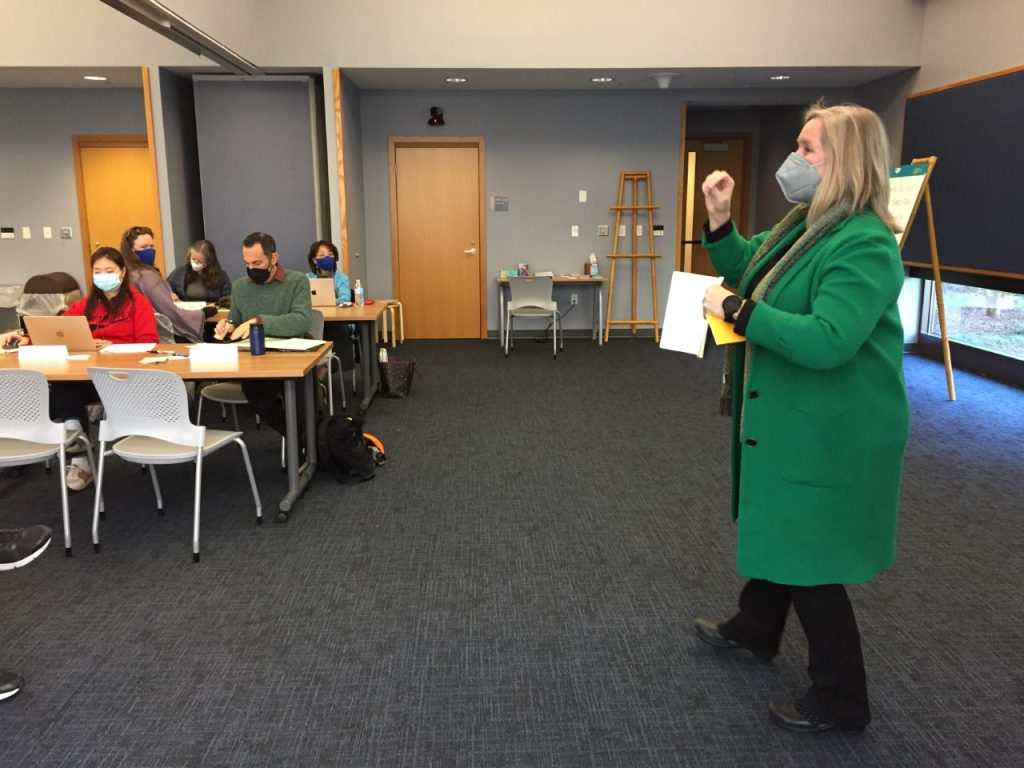

The Kenan Institute of Ethics recently held a conversation to discuss exactly that issue. The discussion was moderated by Jesse Summers, Ph.D., and featured speakers Erich Hatala Matthes, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Philosophy at Wellesley College and author of “Drawing the Line: what to do with the work of immoral artists from museums to the movies,” and Tom Rankin, Professor of the Practice of Art and Documentary Studies and Director of the MFA in Experimental and Documentary Arts at Duke University.

Why should we care about morality in art, anyway? Why not just appreciate the art and separate it from the artist?

Matthes believes that in some cases, “to not engage with the moral dimensions of a work would be to not take the work seriously.” He thinks Shakespeare’s works belong in this category. “Trickier cases,” he adds, “might come from works that aren’t explicitly engaged” with morality, but even in those cases, “the moral life of the artist can actually become a lens through which to read aspects of the work.”

We already consider context when viewing art, not just “formal features of the work.” What was the artist responding to? What were the politics at the time? Matthes believes it makes sense to consider the “moral life” of the artist, too. That “doesn’t mean the artist’s moral life is always going to be relevant” to engaging with the art, but he thinks it’s worth at least acknowledging.

According to Rankin, “When we look at a piece of art or hear something, what we hope is that it propels us” to consider moral issues. How, he asks, can we not look at a painting or photo and wonder, “Where did this come from? Who made it? What was their agenda? What is their point of view? What was their background?”

So where does that leave us, Rankin asks, when it comes to “work that was made a hundred years ago but is really powerful… and yet when we look at it a hundred years later it has all kinds of flaws?” Should museums remove paintings by famous artists if racist or sexist views come to light? Should individuals boycott books, songs, and video games created (or inspired) by artists who have made harmful statements toward individuals or groups of people? How should college classes address works by immoral artists?

Matthes says the term “immoral artists” in his book is intentionally provocative. “I don’t actually think it’s productive” to think of people as good or bad, moral or immoral, he says. “There’s a huge range” in the morality or lack thereof in artists’ actions, and Matthes believes there should also be a range in our responses, but he doesn’t believe that “great art can ever just excuse immorality.” He wants to reject the idea that “artists need to be a little inhuman” and “outside the norms of society.” He thinks that mindset encourages us to think of artists as not subject to the same rules. They should not be “immune to moral criticism,” he says.

Rankin agrees: “I do balk a little bit at having to be the one to decide who’s bad and who’s good,” but at the same time, he believes that “artists make work in response to who they are.” So “What do we confront first? The life of the artist or the work itself? It’s not one or the other,” he says.

Both speakers believe that context is often key to interpreting and evaluating art. Matthes says that it might be “really obscene” to choose Michael Jackson music at your wedding if you know one of your guests has experienced child abuse, given the child sexual assault allegations against Jackson. However, Matthes doesn’t believe that completely “cancelling” Jackson’s music is the solution, either.

Similarly, Matthes doesn’t believe that “we should necessarily continue with big exhibitions honoring Paul Gauguin,” a painter who had sexual relationships with young girls and employed racist terminology. According to Matthes, Gauguin “represents a paternalistic energy of a particular time” that we should “interrogate.” As for the notion that we should extend a degree of lenience to historical artists and view them as a product of their times, Matthes is “disinclined” to think of morality as relative to time period. The time when a work of art was created might affect how we engage with it or assign blame, but “Gauguin did a lot of morally horrific things, and the fact that it was in a different time and place doesn’t change that.”

Nevertheless, Matthes thinks we can and should still engage with and respond to the work of “immoral artists.” His concern, he says, is that taking art off of walls and bookshelves and not talking about it “isn’t reckoning with the legacy.” He also doesn’t “see a reason to put certain types of art on a pedestal and treat them differently…. Artistic expression is a fundamental part of human life.”

What if an individual doesn’t want to engage with such art at all? What if the actions of an artist, dead or alive, are so objectionable to someone that they want nothing to do with it? Matthes is okay with that attitude, though he does think it’s “missing an opportunity.”

Completely disengaging from art on account of its creator’s moral life “feels like a way of not taking the moral criticism seriously,” Matthes says. “It’s not something you would be wrong to fail to do,” but he believes in engaging with moral issues, even those that “it would be easier to just ignore.”

But he acknowledges that personal identities can play a role in how or whether we engage with the work of immoral artists. Matthes believes it’s important to consider “the position you’re coming from” when you read or think about these issues. On the other hand, people and groups who may be more directly impacted by an artist’s problematic views “also have really thoughtful, nuanced ways” of engaging—or not engaging—with the art.

Matthes believes that “we have a lot of moral latitude when it comes to our individual engagement” with art. He finds it difficult to make the argument that reading, listening to, or viewing art in your own home is directly harmful to others, even if the artist in question is still alive.

Summers, meanwhile, points out that if someone is upset by an artist, there could be cases where “you’re taking it out on your friends… when you should be taking it out on the band.”

Institutions like universities, however, might need to take further considerations. “Different moral norms might apply,” Matthes suggests, “based on the positions of power we occupy.” Classrooms, for instance, are a “semi-public” space. They can help provide context in conversations about “morally problematic art” and encourage people to “think really carefully and critically.” If a class is going to engage with such topics, though, Matthes thinks it’s important to spell that out to students beforehand.

Powerful conversations can take place outside of classrooms, too — in book clubs and even informal conversations with friends. “You don’t want to let the moral concerns completely drive the bus” when engaging with art, Matthes says, “but I think it’s important not to ignore them.”

Rankin concludes by reminding us that it isn’t just artists who face decisions about how to respond to the world. For instance, even among those who don’t think of themselves as photographers, anyone who carries a cell phone is making choices every time they take a photo — about what they’re presenting and why.

Post by Sophie Cox, Class of 2025