There are many things in life that are a little easier if one recruits the help of friends. As it turns out, this is also the case with scientific research.

Lilly Chiou, a senior majoring in biology, and Daniele Armaleo, a professor in the Biology Department had a problem. Lilly needed more funding before graduation to initiate a new direction for her project, but traditional funding can sometimes take a year or more.

So they turned to their friends and sought crowdfunding.

Chiou and Armaleo are interested in lichens, low-profile organisms that you may have seen but not really noticed. Often looking like crusty leaves stuck to rocks or to the bark of trees, they — like most other living beings — need water to grow. But, while a rock and its resident lichens might get wet after it rains, it’s bound to dry up.

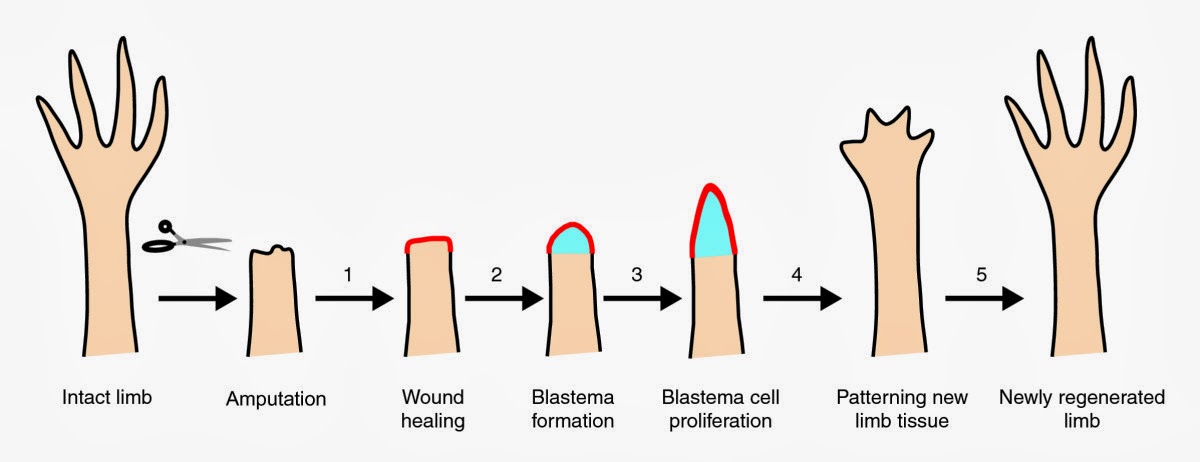

This is where the power of lichens comes in: they are able to dry to a crisp but still remain in a suspended state of living, so that when water becomes available again, they resume life as usual. Few organisms are able to accomplish such a feat, termed desiccation tolerance.

Chiou and Armaleo are trying to understand how lichens manage to survive getting dried and come out the other end with minimal scars. Knowing this could have important implications for our food crops, which cannot survive becoming completely parched. This knowledge is ever more important as climate becomes warmer and more unpredictable in the future. Some farmers may no longer be able to rely on regular seasonal rainfall.

They are using genetic tools to figure out the mechanisms behind the lichen’s desiccation tolerance[. Their first breakthrough came when they discovered that extra DNA sequences present in lichen ribosomal DNA may allow cells to survive extreme desiccation. Now they want to know how this works. They hope that by comparing RNA expression between desiccation tolerant and non-tolerant cells they can identify genes that protect against desiccation damage.

As with most things, you need money to carry out your plans. Traditionally, scientists obtain money from federal agencies such as the National Science Foundation or the National Institutes of Health, or sometimes from large organizations such as the National Geographic Society, to fund their work. But applying for money involves a heavy layer of bureaucracy and long wait times while the grant is being reviewed (often, grants are only reviewed once a year). But Chiou is in her last semester, so they resorted to crowdfunding their experiment.

This is not the first instance of crowdfunded science in the Biology Department at Duke. In 2014, Fay-Wei Li and Kathleen Pryer crowdfunded the sequencing of the first fern genome, that of tiny Azolla. In fact, it was Pryer who suggested crowdfunding to Armaleo.

Chiou was skeptical that this approach would work. Why would somebody spend their hard-earned money on research entirely unrelated to them? To make their sales pitch, Chiou and Armaleo had to consider the wider impact of the project, rather than the approach taken in traditional grants where the focus is on the ways in which a narrow field is being advanced.

What they were not expecting was that fostering relationships would be important too; they were surprised to find that the biggest source of funding was their friends. Armaleo commented on how “having a long life of relationships with people” really shone through in this time of need — contributions to the fund, however small, “highlight people’s connection with you.” That network of connections paid off: with 18 days left in the allotted time, they had reached their goal.

After their experience, they would recommend crowdfunding as an option for other scientists. Having to create widely understood, engaging explanations of their work, and earning the support and encouragement of friends was a very positive experience.

“It beats writing a grant!” Armaleo said.

Guest Post by Karla Sosa, Biology graduate student