In an era of seemingly endless panaceas for age-based mental decline, navigating through the clutter can be a considerable challenge.

However, a team of Duke researchers, led by cognitive neuroscientist Edna Andrews, PhD, think they may have found a robust and long-term solution to countering this decline and preventing pathologies in an aging brain. Their approach does not require an invasive procedure or some pharmacological intervention, just a good ear, some sheet music, and maybe an instrument or two.

In early 2021, Andrews and her team published one of the first studies to look at musicianship’s impact in building cognitive brain reserve. Cognitive brain reserve, simply put, is a way to qualify the resilience of the brain in the face of various pathologies. High levels of cognitive reserve can help stave off dementia, Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis for years on end. These levels are quantified through structural measurements of gray matter and white matter in the brain. The white matter may be thought of as the insulated wiring that helps different areas of the brain communicate.

In this particular study, Andrews’ team focused on measurements of white matter integrity through an advanced MRI technique known as diffusion tensor imaging, to see what shape it is in.

Previous neuroimaging studies have revealed that normal aging leads to a decrease in white matter integrity across the brain. Over the past fifteen years, however, researchers have found that complex sensory-motor activities may be able to slow down and even reverse the loss of white matter integrity. The two most robust examples of complex sensory-motor activities are multilingualism and musicianship.

Andrews has long been fascinated by the brain and languages. In 2014, she published one of the seminal texts in the field of cognitive neurolinguistics where she laid the groundwork for a new neuroscience model of language. Around the same time, she published the first and to-date only longitudinal fMRI study of second language acquisition. Her findings, built upon decades of research in cognitive neuroscience and linguistics, served as the foundation for her popular FOCUS course: Neuroscience/Human Language.

In more recent years, she has shifted her research focus to understanding the impact of musicianship on cognitive brain reserve. Invigorated by her lived experience as a professional musician and composer, she wanted to see whether lifelong musicianship could increase white matter integrity as one ages. She and her team hypothesized that musicianship would increase white matter integrity in certain fiber tracts related to the act of music-making

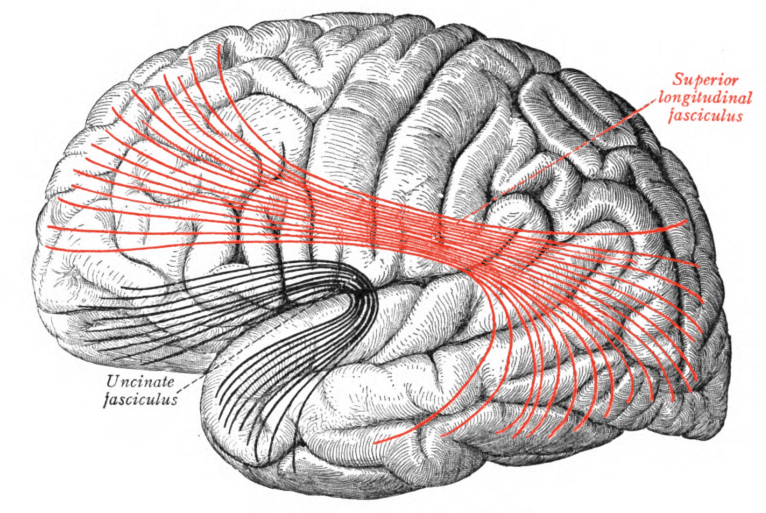

To accomplish this goal, she and her team scanned the brains of eight different musicians ranging in age from 20 years to 67 years old. These musicians dedicated an average of three hours per day to practice and had gained years’ worth of performance experience. After participants were placed into the MRI machine, the researchers used diffusion tensor imaging to calculate fractional antisotropy (FA) values for certain white matter fiber tracts. A higher FA value meant higher integrity and, consequently, higher cognitive brain reserve. Andrews and her team chose to observe FA values in two fiber tracts, the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) and the uncinate fasciculus (UF), based on their relevance to musicianship in previous studies.

Previous studies of the two fiber tracts in non-musicians found that their integrity decreased with age. In other words, the older the participants, the lower their white matter integrity in these regions. After analyzing the anisotropy values via linear regression, they observed a clear positive correlation between age and fractional anisotropy in both fiber tracts. These trends were visible in both tracts of both the left and right hemispheres of the brain. Such an observation substantiated their hypothesis, suggesting that highly proficient musicianship can increase cognitive brain reserve as one ages.

These findings expand the existing literature of lifestyle changes that can improve brain health beyond diet and exercise. Though more demanding, neurological changes resulting from the acquisition and maintenance of language and music capabilities have the potential to endure longer into the life cycle.

Andrews is one of the strongest advocates of lifelong learning, not solely for the satisfaction it brings about, but also for the tangible impact it can have on cognitive brain reserve. Picking up a new language or a new instrument should not be pursuits confined to the young child.

It appears, then, that the kindest way to treat the brain is to throw something new at it. A little bit of practice couldn’t hurt either.