In the first week of fall semester, four first-year engineering students, Sean Burrell, Teya Evans, Adam Kramer, and Eloise Sinwell, had a brainstorming session to determine how to create a set of physical therapy stairs designed for children with disabilities. Their goal was to construct something that provided motivation through reward, had variable step height, and could physically support the students.

Evans explained, “The one they were using before did not have handrails and the kids were feeling really unstable.”

Teya Evans is pictured stepping on the staircase her team designed and built. With each step, the lightbox displays different colors.

The team was extremely successful and the staircase they designed met all of the goals set out by their client, physical therapists. It provided motivation through the multi-colored lightbox, included an additional smaller step that could be pulled out to adjust step height, had a handrail to physically support the students and could even be taken apart for easy transportation.

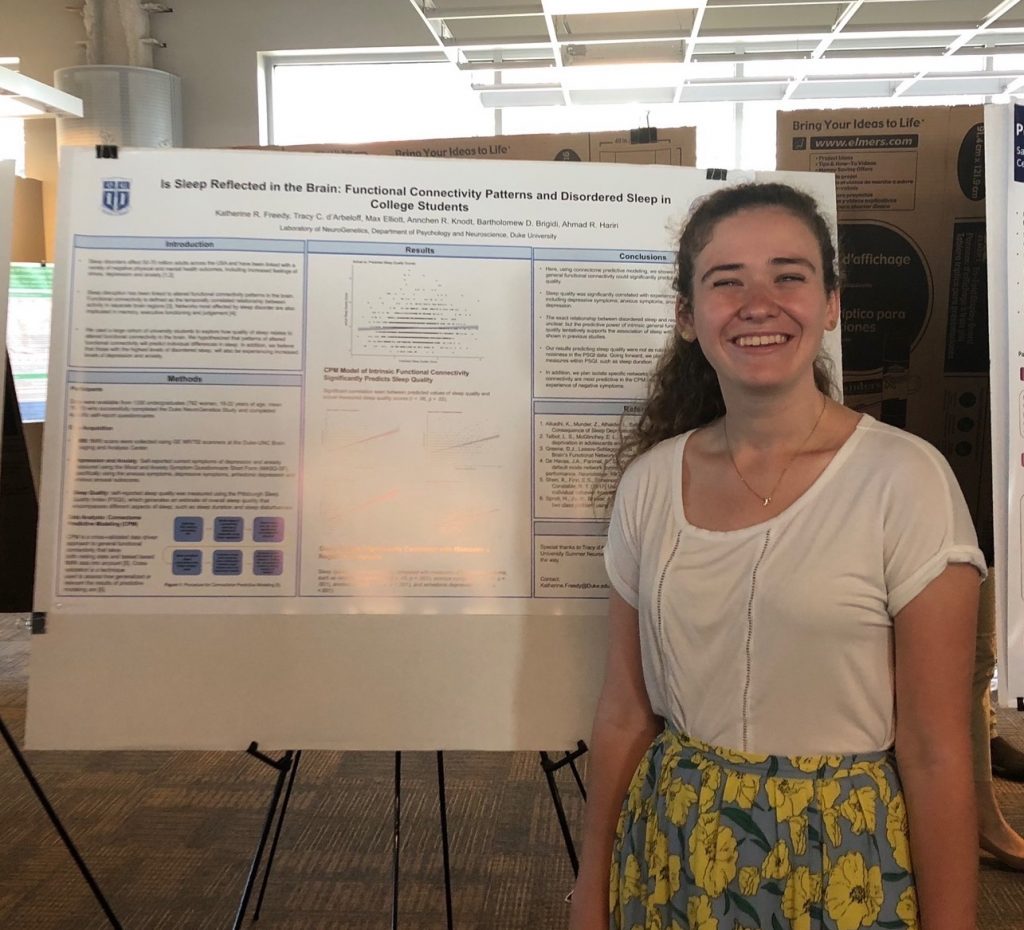

This is a part of the Engineering 101 course all Pratt students are required to take. Teams are paired with a real client and work together throughout the semester to design and create a deliverable solution to the problem they are presented with. At the end of the semester, they present their products at a poster presentation that I attended. It was pretty incredible to see what first-year undergraduates were able to create in just a few months.

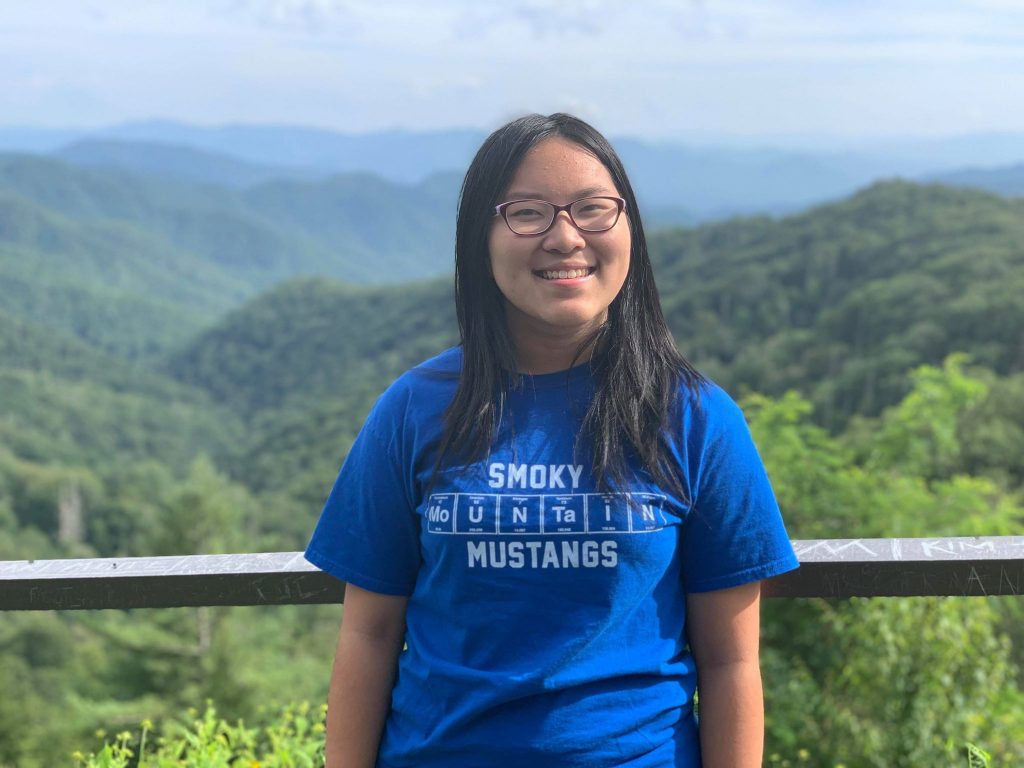

The next poster I visited focused on designing a device to stabilize hand tremors. The team’s client, Kate, has Ataxia, a neurological disorder that causes her to have uncontrollable tremors in her arms and hands. She wanted a device that would enable her to use her iPad independently, because she currently needs a caregiver to stabilize her arm to use it. This team, Mohanapriya Cumaran, Richard Sheng, Jolie Mason, and Tess Foote, needed to design something that would allow Kate to access the entire screen while stabilizing tremors, being comfortable, easy to set up and durable.

The team was able to accomplish its task by developing a device that allowed Kate to stabilize her tremors by gripping a 3D printed handlebar. The handlebar was then attached to two rods that rested on springs allowing for vertical motion and a drawer slide allowing for horizontal motion.

“We had her [Kate] touch apps in all areas of the iPad and she could do it.” Foote said. “Future plans are to make it comfier.”

The team plans to improve the product by adding a foam grip to the handlebar, attaching a ball and socket joint for index finger support, and adding a waterproof layer to the wooden pieces in their design.

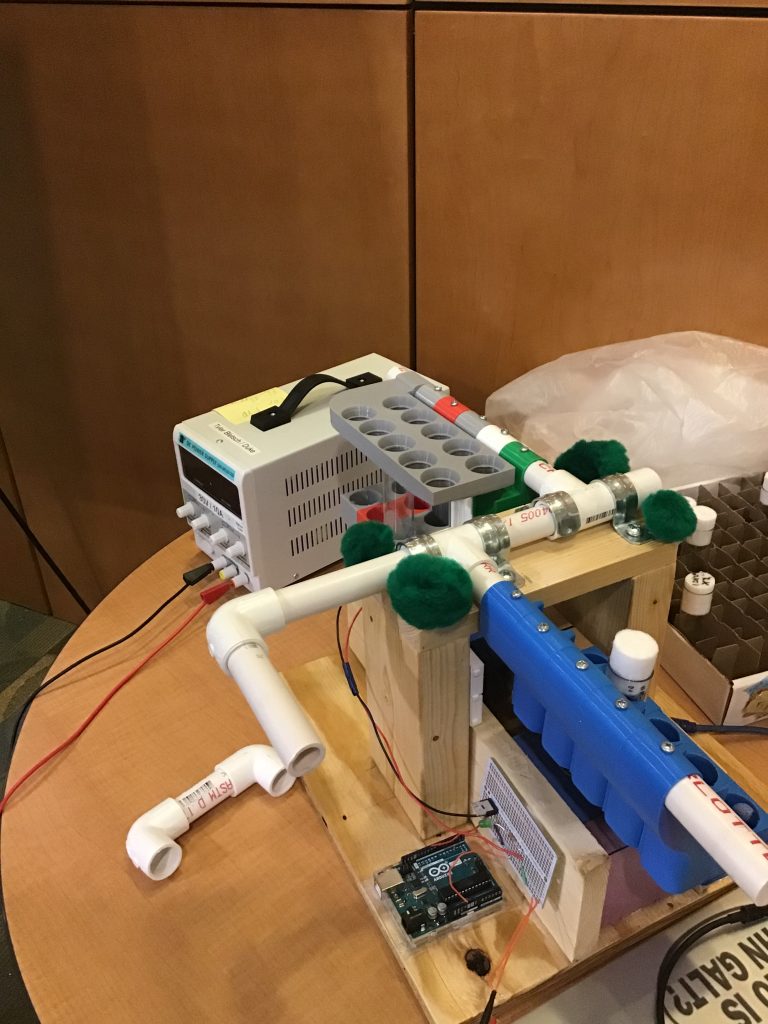

The last project I visited created a “Fly Flipping Device.” The team, C. Fischer, E. Song, L. Tarman, and S. Gorbaly, were paired with the Mohamed Noor Lab in the Duke Biology Department as their client.

Tarman explained, “We were asked to design a device that would expedite the process of transferring fruit flies from one vial to another.”

The Noor lab frequently uses fruit flies to study genetics and currently fly flipping has to be done by hand, which can take a lot of time. The goal was to increase the efficiency of lab experiments by creating a device that would last for more than a year, avoid damaging the vials or flies, was portable and fit within a desk space.

The team came up with over 50 ideas on how to accomplish this task that they narrowed down to one that they would build. The product they created comprised of two arms made of PVC pipe resting on a wooden base. Attached to the arms were “sleeves” 3D printed to hold the vials containing flies. In order to efficiently flip the flies, one of the arms moves about the axis allowing for multiple vials to be flipped that the time it would normally take to flip one vial. The team was very successful and their creation will contribute to important genetic research.

It was mind-blowing to see what first-year students were able to create in their first few months at Duke and I think it is a great concept to begin student education in engineering through a hands-on design process that allows them to develop a solution to a problem and take it from idea to implementation. I am excited about what else other EGR 101 students will design in the future.