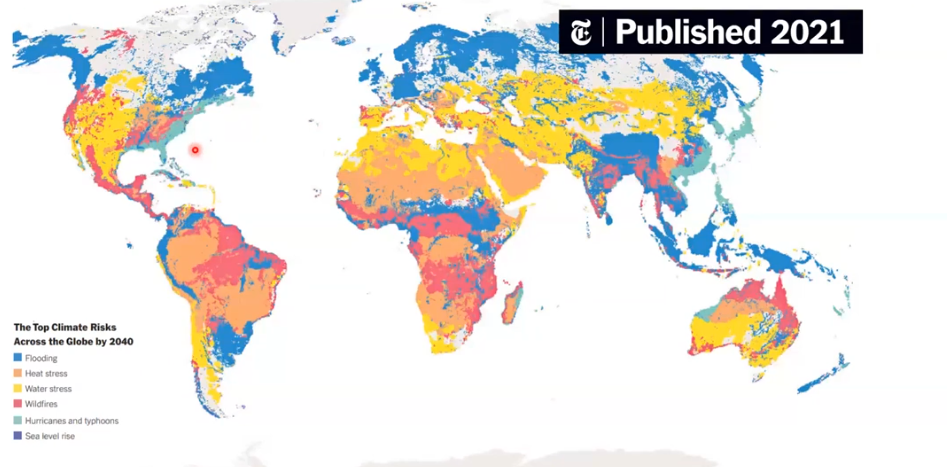

A recent study about maternal deaths at Kawempe National Referral Hospital in Uganda found that “as many as 1 in 50 maternal deaths worldwide occur in Uganda.” Moreover, between 2016 and 2018, around 84% of maternal deaths within the hospital alone were considered preventable.

Each year, over 70,000 women die from postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), making it the leading cause of maternal mortality in the world. At hospitals like Kawempe, the challenge is further exacerbated by the inability to quantitatively distinguish blood loss from other fluids lost during pregnancy, such as amniotic fluid.

“We noticed no sort of formal collection of blood or fluid,” said Haasini Nandyala, a senior biomedical engineering student at Duke University. “It was all randomly mopped up, and then blood would just go everywhere.”

Despite the ever-present issue of PPH, blood transfusions remain uncommon in Uganda. The combined factors of limited blood donation centers and lingering fears of the HIV pandemic continue to exacerbate the blood scarcity crisis. As a result, the team saw a clear direction: faster detection of hemorrhage was critical, and the current standards were inadequate.

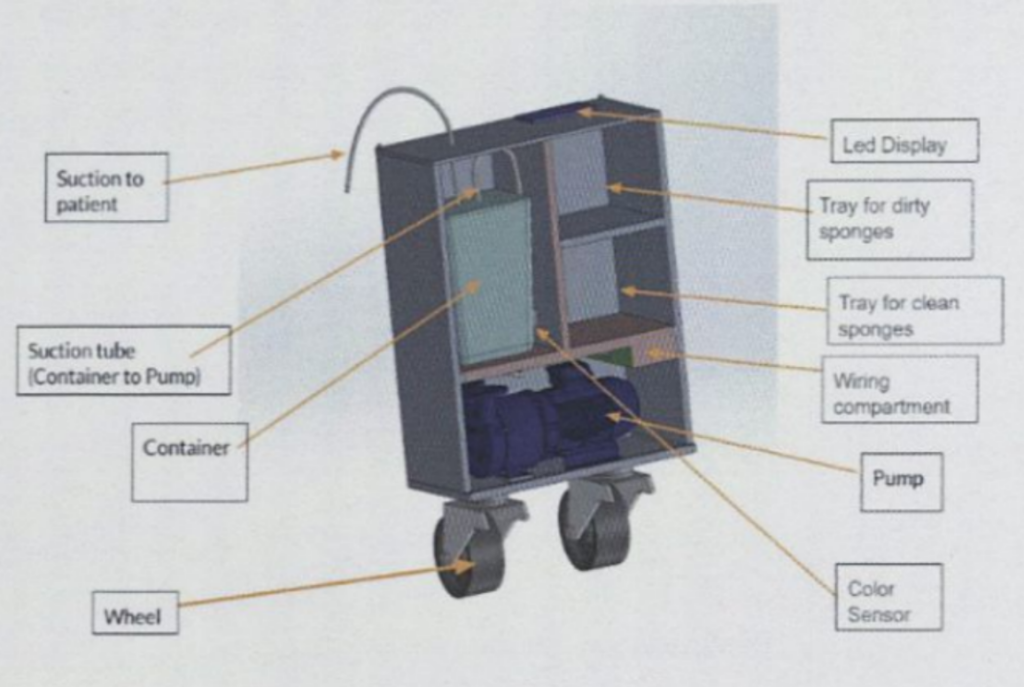

From there, HemoSavetook root. Created by a team of engineering students from Duke and Uganda’s Makerere University – Haasini Nandyala, James Bradley, Mohammed Farah, Desmond Boateng, Joel Mugabo, and Samantha Keshara – the portable, low-cost device measures blood loss during cesarean sections (C-sections) in real-time and signals to the physicians when the patient is nearing a dangerous level of blood loss.

“We wanted our device to be easy to use and only require one person to operate because we saw how much of a workforce shortage there is,” said Nandyala. “There would usually be one surgeon and one nurse in every operating room, that’s it. One surgeon could do ten to twelve C-sections a day.”

The device measures blood loss through two main pathways. The first is collecting fluid through aspiration (i.e., a suction pump) before measuring the amount of the bodily fluid that is blood (using color and weight analysis). Simultaneously, the second method collects the blood soaked into medical cloths and compares the weight before and after use to determine the volume contributed to blood.

The system is able to monitor and warn when the blood loss exceeds eight hundred milliliters. Doing so provides clinicians with a better sense of real-time blood loss, prompting earlier interventions before childbirth becomes fatal for the mother.

Currently, HemoSave is now working towards patenting in Uganda and clinical implementation. Moreover, Nandyala aims to return to Uganda this summer to help refine the manufacturing process and bring the product to market.

For the students, being part of HemoSave has been as much a learning experience as it has been a technical achievement. The team navigated engineering challenges and cross-continental communication while also ensuring all the device’s parts were locally sourced. “This project has shown me what having a passion is like.” Bradley added, “It’s been awesome working with an international team, with our teammates in Uganda.”

Postpartum hemorrhage remains a critical, life-threatening issue that impacts thousands of mothers each year. But HemoSave’s impactful work highlights the possibility of a future where concerns over fatal blood loss during childbirth no longer exist.

“One of our biggest motivations for this whole project is that we’ve seen [post-partum hemorrhage], and we know that it’s an avoidable problem,” said Nandyala. “We truly believe that no matter where you live, no child deserves to grow up without their mother.”