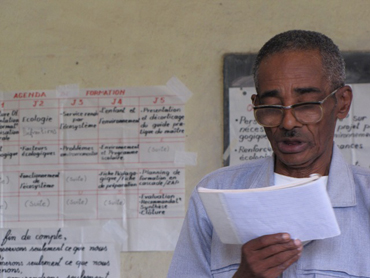

Mr. Gimod, an education specialist, reads notes taken from the Malagasy Teacher's Guide, a teaching tool to help preserve the country's lemurs and biodiversity. Courtesy of Lanto Andrianandrasana.

By Ashley Yeager

Halfway around the world, in Madagascar’s northeastern city of Sambava, 30 students crowded into a classroom to start lessons in biology and conservation.

These students weren’t your average school children, however.

They were mostly Chefs ZAP, officials from the local school districts in Sambava and another nearby city, Andapa.

People in these cities “are not yet conscious” that it’s urgent to protect the biodiversity in this region, says Lanto Andrianandrasana, a Malagasy field assistant and who helped organize the lessons.

The lessons are to help individuals there to appreciate and understand the importance of the environment through a new Duke Lemur Center conservation initiative.

One reason the center chose to develop a new conservation education initiative in Sambava is because the nearby national parks are experiencing devastating effects from illegal logging and lemur trapping.

In 2009, armed gangs began harvesting rosewood trees worth hundreds of millions of dollars and trapping and killing critically endangered lemur species after a military coup overthrew democratically elected president, Marc Ravalomanana. The illegal activity continues, with the wood being shipped to China for use in high-end furniture and the lemurs eaten or sold as bushmeat.

Andrianandrasana, who is the on the ground coordinator for the DLC conservation initiative, says that to protect the lemurs and the rosewood trees in the region, the people must learn to love them. He says they need to understand the importance of the environment, and that’s why it is essential to give them basic biology knowledge, particularly in primary and secondary school.

Through the initiative, he and others will train the Chefs ZAP to use a Malagasy-prepared Teacher’s Guide, which discusses the biology of the rosewood and lemur populations and the environmental strategies to preserve them, along with other conservation topics.

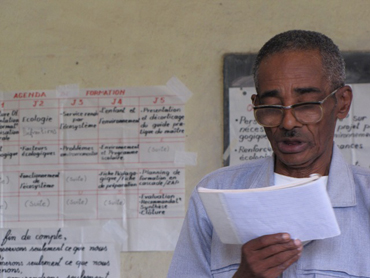

The Chefs ZAP will then share the guide with the directors of the schools in the region. The directors are then to train their teachers to use the guide so they can share it with their students. This is a training cascade technique that has worked in schools in other eastern Madagascar cities to encourage enthusiasm for environmental issues not only among teachers and students, but also adults in the community, says Duke Lemur Center conservation coordinator Charlie Welch.

Welch worked with Andrianandrasana and other Malagasy conservationists to plan and implement the new initiative. The lessons and the Teacher’s Guide are borrowed from an already successful conservation initiative run by the MFG, or Madagascar Fauna Group. The Duke Lemur Center, or DLC, is a founding and managing participant of this 27-member group, which for the past ten years has sponsored Malagasy education specialists to train teachers in the Tamatave region in environmental education.

The Chefs Zap from Andapa and Sambava after their biology and conservation training. Courtesy of Lanto Andrianandrasana.

But Welch and others at DLC thought the center could “do more” to broaden the efforts of the MFG, he says. Using DLC grants and donations, Welch arranged for the most experienced MFG trainers, along with Andrianandrasana, to work with the local Chefs ZAP in Sambava and Andapa.

The first session was on Aug. 15, and the trainings will continue through the school year.

Welch, meanwhile, has been working with other Duke departments, including four masters students in the Nicholas School who will evaluate the trainings, to further develop the education initiative.