Guest Post By Sheena Faherty, Ph.D. Candidate in Biology

Dame Alison Richard is the epitome of someone who puts her money where her mouth is. And her dedication is directed precisely where it’s needed most.

Richard, a protector of lemurs, artisanal salt entrepreneur and endless optimist, is not just doing something about Madagascar’s conservation crisis. She’s doing everything about it.

She’ll visit Duke March 3-5 to give three-part lecture series discussing her role in over forty years of community-based conservation efforts in Madagascar.

Members of the Duke community know all too well that our beloved lemurs— many of which can only be found at the Duke Lemur Center or in Madagascar—are in dire straights.

Their plight has been a life’s work for Richard, who is best known for her research on sifakas in the spiny forests of Madagascar. But she also lays claim to having been the first female vice-chancellor at Cambridge. She has now returned to Yale, where she spent most of her career, as a senior research scientist and professor emerita.

“Sometimes I think that because I’m covering so many bases, I end up doing nothing very well,” Richard said. “But it’s what I do and I can’t imagine not doing any of them—so it’s too bad,” she said laughing.

Richard is a conservationist who understands that without considering the local people’s well-being, all attempts to save wildlife habitats will fail.

“There are a variety of ways in which we are trying to facilitate socio-economic enhancements to people’s lives,” Richard said. “[On a recent trip to Madagascar] I met with the association of women salt producers, who are producing artisanal salt by techniques that have been in place for hundreds of years.”

In collaboration with a start-up company that is highly focused on sustainability, she recently shipped the first 500 kilos of the Madagascan salt to the U.S.

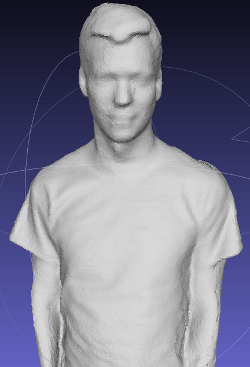

Verreaux’s Sifaka, a favorite of Richard’s in Southwestern Madagascar. (Credit: Flickr user nomis-simon, CC)

Taking time away from protecting the lemurs and enhancing the lives of the Malagasy people, Richard said her Duke lectures will have broad appeal for anyone interested in conservation, or for those who just enjoy seeing adorable pictures of lemurs.

She hopes to focus on writing a book, the topic of which will draw from her public lecture on March 5 at 6:00 pm at the Great Hall of the Mary Duke Biddle Trent Semans Center for Health Education. This lecture is set to explore how an array of different sciences has changed our understanding of Madagascar’s history.

And the conservationist who said she does everything has some advice for conserving her own mental sanity.

“One thing I need to do going forward is to find things to stop doing,” she admits. “And I’m not good at that because they are all too interesting and seemingly too important,” she said.

So, what’s next for Alison Richard?

“More of doing everything!” she said.