Fractions strike fear in the hearts of many grade schoolers – but a new study reveals that they don’t pose a problem for monkeys.

Even as adults, many of us struggle to compute tips, work out our taxes, or perform a slew of other tasks that use proportions or percentages. Where did our teachers and parents go wrong when explaining discounts and portions of pie? Are our brains simply not built to handle quantitative part-whole relationships?

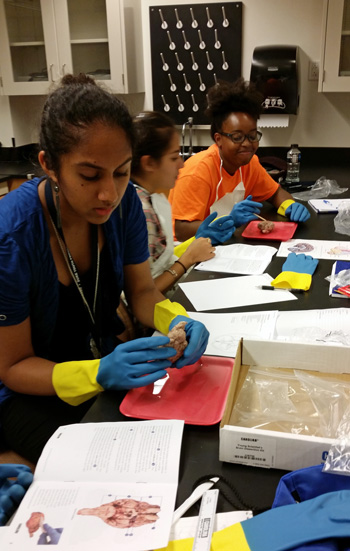

Fractions and logical relationships are some of the things a wild macaque might think about while grooming and being groomed. (image copyright Lauren Brent)

To try to answer these questions, my colleagues and I wanted to test whether other species understand fractions. If our fellow primates can reason about proportions, our minds likely evolved to do so too.

In our study, which appears online in the journal Animal Cognition, Marley Rossa (Trinity 2014), Dr. Elizabeth Brannon, and I asked whether rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) are able to compare ratios.

We let the monkeys play on a touch-screen computer for a candy reward. First we trained them to distinguish between two shapes that appeared on the screen: a black circle and a white diamond. When they touched the black circle, they heard a ding sound and received a piece of candy. But when they touched the white diamond, they heard a buzz sound and did not get any candy. The candy-loving monkeys quickly developed a habit of choosing the rewarding black circle.

Next we introduced fractions. We showed two arrays on the screen, each with several black circles and white diamonds. The monkeys’ job was to touch the array having a greater ratio of black circles to white diamonds. For example, if there were three black circles and nine white diamonds on the left, and eight black circles and five white diamonds on the right, the monkey needed to touch the right side of the screen to earn her candy (8:5 is better than 3:9).

We didn’t always make it so easy, though. Sometimes both arrays had more black circles than white diamonds, or vice versa. Sometimes the array with the higher black-circle-to-white-diamond ratio actually had fewer black circles overall. They needed to find the largest fraction of black circles. For example, if there were eight black circles and 16 white diamonds on the left (8:16), and five black circles and six white diamonds on the right (5:6), the correct answer would be the latter, even though there were more black circles on the left side. That is how we made sure that monkeys were paying attention to the relative numbers of shapes in both arrays.

The monkeys were able to learn to compare proportions. They chose the array with the higher black-circle-to-white-diamond ratio about three-quarters of the time. Impressively, when we showed them new arrays with number combinations they had never seen before, the monkeys still tended to select the array with the better ratio.

Our results suggest that monkeys understand the magnitude of ratios. They also indicate that monkeys might be able to answer another type of question: analogies. These four-part statements you may have seen on standardized tests take the form “glove is to hand as sock is to foot.”

This kind of reasoning requires not only recognizing the relationship between two items (glove and hand) but also how that relationship compares with the relationship between the other two items (sock and foot). Understanding the relationships between relationships — that is, second-order relationships — was believed to require language, making it possibly a uniquely human ability. But in our study, monkeys successfully determined the relationship between two fractions – each one a relationship between two numbers – to make their choices.

If monkeys can reason about ratios and maybe even analogies, our minds are likely to have been set up with these skills as well.

The next step for this line of research will be to figure out how best to employ these in-born abilities when teaching proportions, percentages, and fractions to human children.

CITATION: “Comparison of discrete ratios by rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta)” Caroline B. Drucker, Marley A. Rossa, Elizabeth M. Brannon. Animal Cognition, Aug. 19, 2015. DOI: 10.1007/s10071-015-0914-9

Guest post by graduate student Caroline B. Drucker. Caroline is curious about both the evolutionary origins and neural basis of numerical cognition, which she currently studies in lemurs and rhesus monkeys.