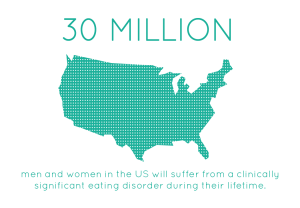

Binge eating disorder is the most prevalent eating disorder in the United States. Infographic courtesy of Multi-Service Eating Disorders Association

With more than a third of the adult population of the United States meeting criteria for obesity, doctors are becoming increasingly interested in behaviors that contribute to these rates.

Allan Kaplan, MD, of the University of Toronto, is interested in eating disorders, specifically binge eating disorder, which is observed in about 35 percent of people with obesity.

Binge eating disorder (BED) is a pattern of disordered eating characterized by consumption of a large number of calories in a relatively short period of time. In addition to these binges, patients report lack of control and feelings of self-disgust. Because of these patterns of excessive caloric intake, binge eating disorder and obesity go hand-in-hand, and treatment of the disorder could be instrumental in decreasing rates of obesity and improving overall health.

In addition to the health risks associated with obesity, binge eating disorder is associated with anxiety disorders, affective disorders, substance abuse and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) – in fact, about 30 percent of individuals with binge eating disorder also have a history of ADHD.

Binge eating disorder displays a high comorbidity with mood and affective disorders. Infographic courtesy of American Addiction Centers.

ADHD is characterized by inability to focus, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, and substance abuse involves cravings and patterns of losing control followed by regret. These patterns of mental and physiological sympoms resemble those seen in patients with binge eating disorder. Kaplan and other researchers are linking the neurological patterns observed in these disorders to better understand BED.

Researchers have found that the neurological pathways become active when a patient with binge eating disorder is provided with a food-related stimulus. Individuals with the eating disorder are more sensitive to food-related rewards than most people. Researchers have also identified a genetic basis — certain genes make individuals more susceptible to reward and thus more likely to engage in binges.

Because patients with ADHD exhibit similar neurological patterns, doctors are looking to drugs already approved by the FDA to treat ADHD as possible treatments for binge eating disorder. The first of these approved drugs, Vyvanse, has proven not much better than the traditional form of treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy, a form of talk therapy that aims to identify and correct dysfunctions in behavior and thought patterns that lead to disordered behaviors.

Another drug, however, proved promising in a study conducted by Kaplan and his colleagues. The ADHD drug methylphenidate, combined with CBT, led to significant clinical outcomes — pateints engaged in less binges and cravings and body mass index decreased. Kaplan argues that the most effective treatment would reduce binges, treat physiological symptoms like obesity, improve psychological disturbances like low self-esteem, and, of course, be safe. So far, the combination of psychostimulants like methylphenidate and CBT have met these criteria.

Kaplan emphasized a need to make information about binge eating disorder and its treatments more available. Most individuals currently being treated for BED do not obtain treatment knowing they have an eating disorder — they are usually diagnosed only after seeking help with obesity-related health issues or help in weight loss. Making clinicians more familiar with the disorder and its associated behaviors as well as encouraging patients to seek treatment could prove instrumental in combating the current healthcare issue of obesity.