By Nonie Arora

Melissa Chieffe, a Junior Biology major, grew up outside Cleveland, Ohio and arrived at Duke enthusiastic about following a pre-vet path. As a freshman, she began volunteering at the Duke Lemur Center as a technician assistant. Through her work, she became interested in conservation in Madagascar and decided to apply to OTS – South Africa.

Through OTS – South Africa, she had the opportunity to travel all around the region and work on three group research projects, focusing mainly on ecology and conservation in the Kruger National Park.

In the first, she collected data for the Kruger long-term research initiative on vegetation changes caused by elephants. Specifically, she honed in on damage done to AppleLeaf trees (Philenoptera violacea) and assessed damage done to 175 trees of that species in the Kruger National Park. The study looked at bark stripping and toppling of trees caused by elephants. Bark stripping happens when elephants rub their tusks on trees; if the elephants remove too much mark the trees are more likely to die, according to Chieffe.

From their study, her team observed a bottleneck in tree size: the elephants generally knocked trees over before they could reach their mature height. Their preliminary data indicated that higher elephant population densities – combined with frequent burnings in the savannah – made it harder for trees to reach the mature stage.

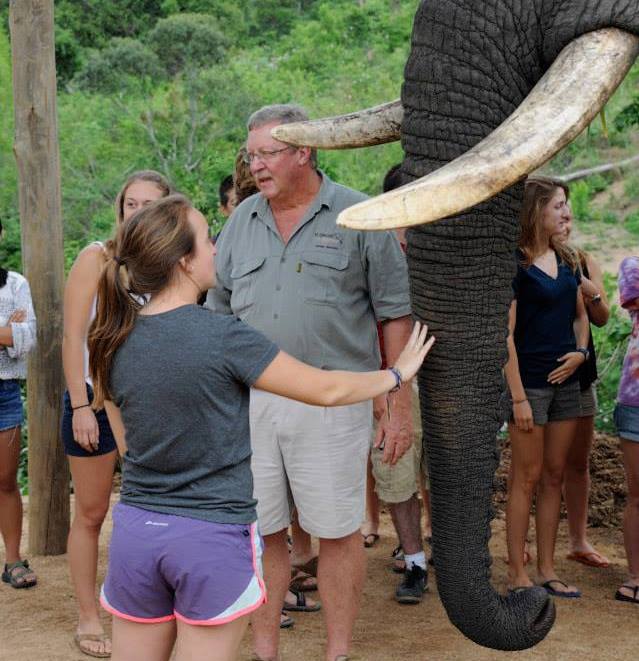

In their independent research project, Chieffe and her group had the opportunity to work with a population of captive elephants. The elephant population in the Kruger National Park has been growing exponentially since the termination of culling operations in the 1990s, which is causing problems for the vegetation and the nearby rural farms, according to Chieffe. The elephants are known to destroy crops, fences, and storage facilities. The students looked into using bee hives as a deterrent for elephants. Chieffe explained that beehive fences could have great applications for conservation through community based conservation initiatives.

They used the sound of bees buzzing & the scent of honey to stand in as surrogates for bee hives. Wild elephants exhibited defensive retreating behaviors when exposed to the bee sounds and scents.

Chieffe learned to use camera traps (above) and made a photo of lion cubs with a camera trap (below). Credit: Melissa Chieffe

In her faculty field project, Chieffe worked with Professor Jeremy Bolton, an expert in the field, and Professor Tali Hoffman from the University of Cape Town to study camera traps. Chieffe’s team set up four camera traps at five different watering holes, which are known to act as “nodes of activity” for wildlife, to compare efficacy of two types of camera traps: field scan and motion sensor. Camera traps can be used to to record endangered animals and to survey biodiversity of an area.

“I enjoyed living in nature reserves, the national park, constantly surrounded by amazing researchers and scientists and others who are involved in conservation management. It was inspiring to live near them. We also got to present our findings to park management, which was awesome,” Chieffe said.

The program has helped her further her ambitions in conservation biology.

“I thought it was a dream [to become a conservation biologist]. But meeting people who are actually doing what I now want to do has made it seem realistic,” Chieffe said. She hopes to continue with her research in South Africa on elephants and vegetation this summer.