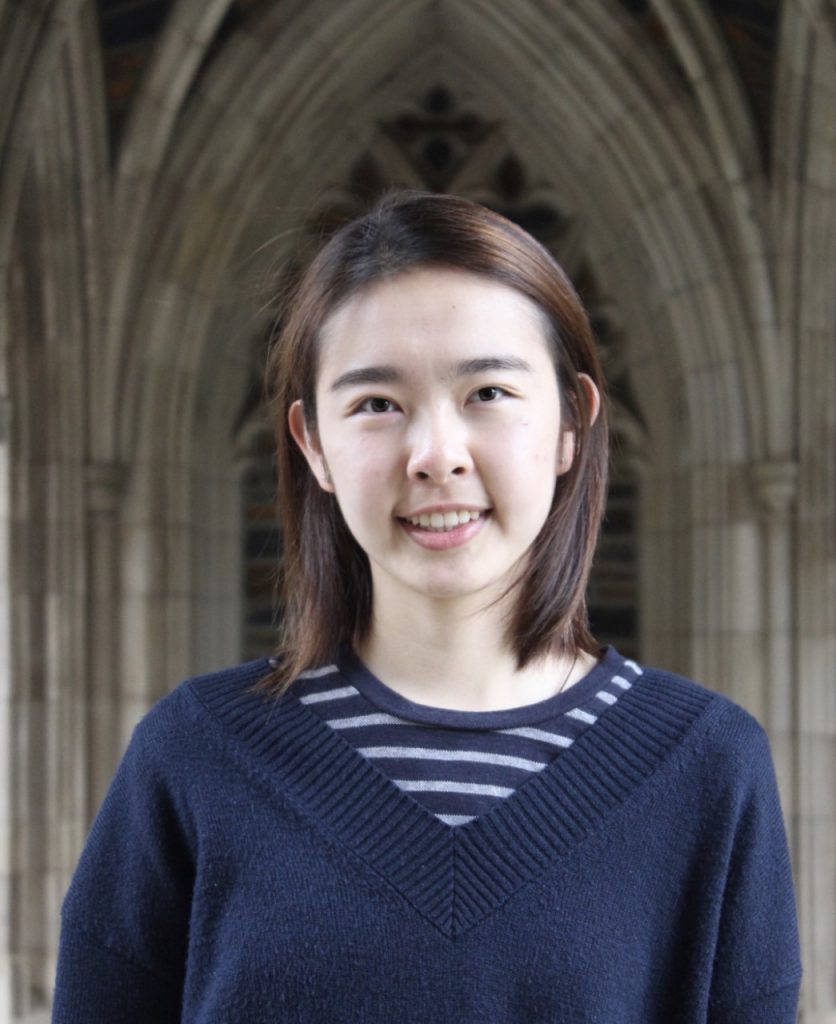

Statistics and computer science double major Jenny Huang (T’23) started Duke as many of us do – vaguely pre-med, undecided on a major – but she knew she had an interest in scientific research. Four years later, with a Quad Fellowship and an acceptance to MIT for her doctoral studies, she reflects on how research shaped her time at Duke, and how she hopes to impact research.

What is it about statistics? And what is it about research?

With experience in biology research during high school and during her first year at Duke, Huang toyed with the idea of an MD/PhD, but ultimately realized that she might be better off dropping the MD. “I enjoy figuring out how the world works” Huang says, and statistics provided a language to examine the probabilistic and often unintuitive nature of the world around us.

In another life, Huang remarked, she might have been a physics and philosophy double major, because physics offers the most fundamental understanding of how the world works, and philosophy is similar to scientific research: in both, “you pursue the truth through cyclic questioning and logic.” She’s also drawn to engineering, because it’s the process of dissecting things until you can “build them back up from first principles.”

Huang’s research and the impact of COVID-19

For Huang, research started her first year at Duke, on a Data+ team, led by Professor Charles Nunn, studying the variation of parasite richness across primate species. To map out what types of parasites interacted with what type of monkeys, the team relied on predictors such as body mass, diet, and social activity, but in the process, they came up against an interesting phenomenon.

It appeared that the more studied a primate was, the more interactions it would have with parasites, simply because of the amount of information available on the primate. Due to geographic and experimental constraints, however, a large portion of the primate-parasite network remained understudied. This example of a concept in statistics known as sampling bias was muddling their results. One day, while making an offhand remark about the problem to one of her professors (Professor David Dunson), Huang ended up arranging a serendipitous research match. It turned out that Dunson had a statistical model that could be applied to the problem Nunn and the Data+ team were facing.

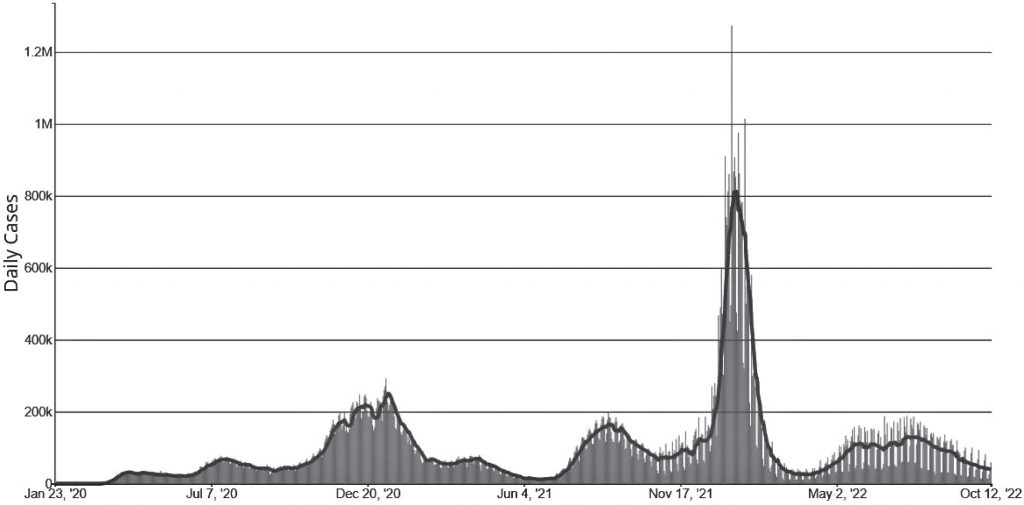

The applicability of statistics to a variety of different fields enamored Huang. When COVID-19 hit, it impacted all of us to some degree, but for Huang, it provided the perfect opportunity to apply mathematical models to a rapidly-changing pandemic. For the past two summers, through work with Dunson on a DOMath project, as well as Professor Jason Xu and Professor Rick Durrett, Huang has used mathematical modeling to assess changes in the spread of COVID-19.

On inclusivity in research

As of 2018, just 28% of graduates in mathematics and statistics at the doctoral level identified as women. Huang will eventually be included in this percentage, seeing as she begins her Ph.D. at MIT’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in the fall, working with Professor Tamara Broderick.

“When I was younger, I always thought that successful and smart people in academia were white men,” Huang laughed. But that’s not true, she emphasizes: “it’s just that we don’t have other people in the story.” As one of the few female-presenting people in her research meetings, Huang has often felt pressure to underplay her more, “girly” traits to fit in. But interacting with intelligent, accomplished female-identifying academics in the field (including collaborations with Professor Cynthia Rudin) reaffirms to her that it’s important to be yourself: “there’s a place for everyone in research.”

Advice for first-years and what the future holds

While she can’t predict where exactly she’ll end up, Huang is interested in taking a proactive role in shaping the impacts of artificial intelligence and machine learning on society. And as the divide between academia and industry is becoming more and more gray, years from now, she sees herself existing somewhere in that space.

Her advice for incoming Duke students and aspiring researchers is threefold. First, Huang emphasizes the importance of mentorship. Having kind and validating mentors throughout her time at Duke made difficult problems in statistics so much more approachable for her, and in research, “we need more of that type of person!”

Second, she says that “when I first approached studying math, my impatience often got in the way of learning.” Slowing down with the material and allowing herself the time to learn things thoroughly helped her improve her academic abilities.

Being around people who have this shared love and a deep commitment for their work is just the human endeavor at its best.

Jenny huang

Lastly, she stresses the importance of collaboration. Sometimes, Huang remarked,“research can feel isolating, when really it is very community-driven.” When faced with a tough problem, there is nothing more rewarding than figuring it out together with the help of peers and professors. And she is routinely inspired by the people she does research with: “being around people who have this shared love and a deep commitment for their work is just the human endeavor at its best.”

Post by Meghna Datta, Class of 2023

(Editor’s note: This is Jenny’s second appearance on the blog. As a senior at NC School of Science and Math, she wrote a post about biochemist Meta Kuehn.)