New maps of Durham released by students in Duke’s Data+ research program show the Bull City as a patchwork of red, white and pink. But what looks like a haphazardly assembled quilt is actually a picture of the socioeconomic realities facing Durham’s 32,000-plus public school students.

The color patches represent the home values across Durham, showing roughly where more and less affluent students live. The darker the red, the higher-priced their housing.

Like cities and neighborhoods, schools face economic disparities too. Research shows that school segregation by race and class in North Carolina has gotten steadily worse over the last three decades.

A 2024 study by North Carolina State University revealed that the typical low-income student attends schools where more than 70% of their classmates are low-income too — a trend that worsens the achievement gap between the richest and poorest children.

A new student assignment plan that Durham Public Schools is rolling out this year aims to combat that trend by redrawing district boundary lines — the thick black lines on the map — to make schools more diverse and equitable.

But if schools are to tackle economic segregation, they’ll need accurate ways to measure it as Durham continues to grow and change.

That was the challenge facing a team in Duke’s Data+ program this summer. For 10 weeks, Duke students Alex Barroso and Dhaval Potdar collaborated with school planners at Durham Public Schools to look at how family wealth and poverty are distributed across the school system.

“Socioeconomic status is a complicated thing,” said Barroso, a Duke junior majoring in statistical science.

For years, the standard way to identify children in need was using free and reduced-price lunch statistics from the National School Lunch Program, along with published income data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

But those numbers can be unreliable, Barroso said.

Changing state and federal policies mean that more districts — including Durham Public Schools — are providing free meals to all students, regardless of their family income. But as a result, schools no longer have an exact count of how many students qualify.

And Census estimates are based on geographic boundaries that can mask important variation in the data when we look more closely.

At a symposium in Gross Hall in July, Barroso pointed to several dark red patches (i.e., more expensive housing) bordering white ones (i.e., more affordable) on one of the team’s maps.

In some parts of the city, homes worth upwards of a million dollars abut modest apartments worth a fraction of that, “which can skew the data,” he said.

The problem with Census estimates “is that everyone who lives in that area is reported as having the same average income,” said team lead Vitaly Radsky, a PhD student at UNC’s School of Education and school planner with Durham Public Schools.

So they took a different approach: using homes as a proxy for socioeconomic status.

Research has confirmed that students from higher-value homes perform better in school as measured by standardized math tests.

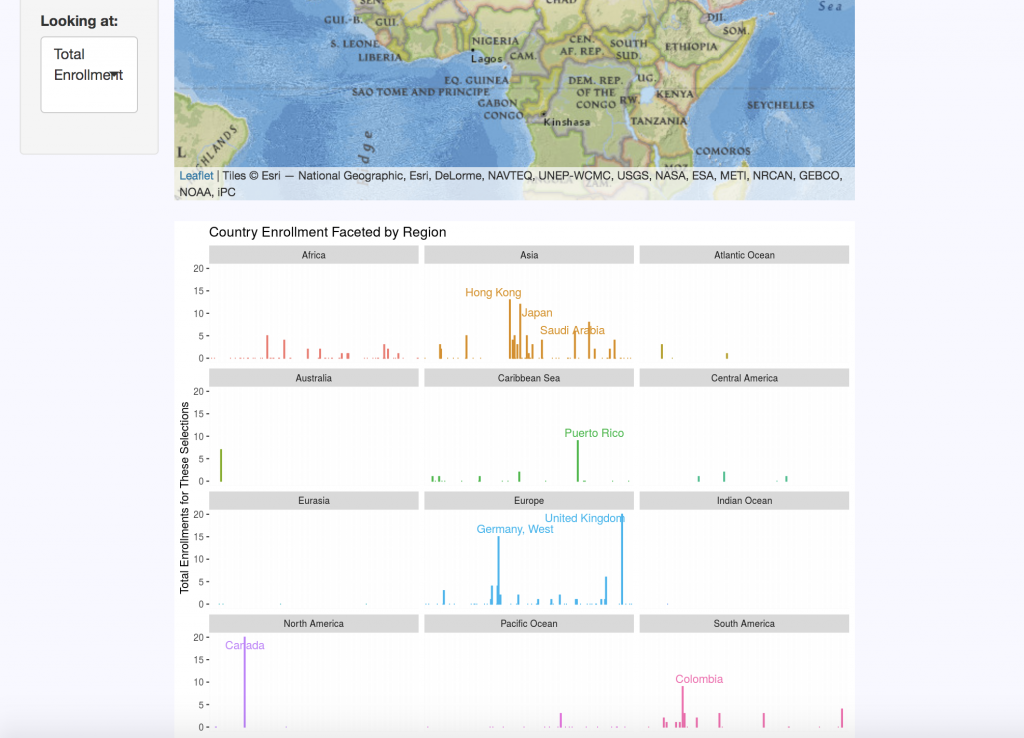

The team created a custom script that fetches publicly available data on every home in Durham from sources such as Durham Open Data and the Census, and then automatically exports it to a dashboard that shows the data on a map.

“Every single house is accounted for within this project,” Barroso said.

They ran into challenges. For example, Census data are tied to tracts that don’t necessarily align with the district boundaries used by schools, said Dhaval Potdar, a graduate student in Duke’s Master in Interdisciplinary Data Science.

One takeaway from their analysis, Potdar said, is no one yardstick sums up the economic well-being of every student.

In Durham, the typical public school student lives in a home valued at about $300,000.

But the picture varies widely when you zoom in on different geographic scales and footprints.

It’s also a different story if you account for the significant fraction of Durham families who live among neighbors in a larger building such as an apartment, townhouse or condominium, instead of a single-family home.

Considering a home’s age can change the picture too.

Generally speaking, students who live in more expensive homes come from more affluent families. But in many parts of the U.S., home prices have far outpaced paychecks. That means a home that has soared in value in the years since it was purchased may not reflect a family’s true economic situation today, particularly if their income remained flat.

The team’s data visualizations aim to let school planners look at all those factors.

There are still issues to be ironed out. For example, there’s some work to be done before planners can make apples-to-apples comparisons between a student whose family owns their home versus renting a similar property, Barroso said.

“No data source is perfect,” but the research offers another way of anticipating the shifting needs of Durham students, Radsky said.

“The traditional metrics really aren’t getting at the granular fabric of the Durham community,” said Mathew Palmer, the district’s senior executive director of school planning and operational services.

Research like this helps address questions like, “are we putting our resources where the kids need them the most? And are schools equitable?”

“This analysis gives schools more tools moving forward,” Palmer said.