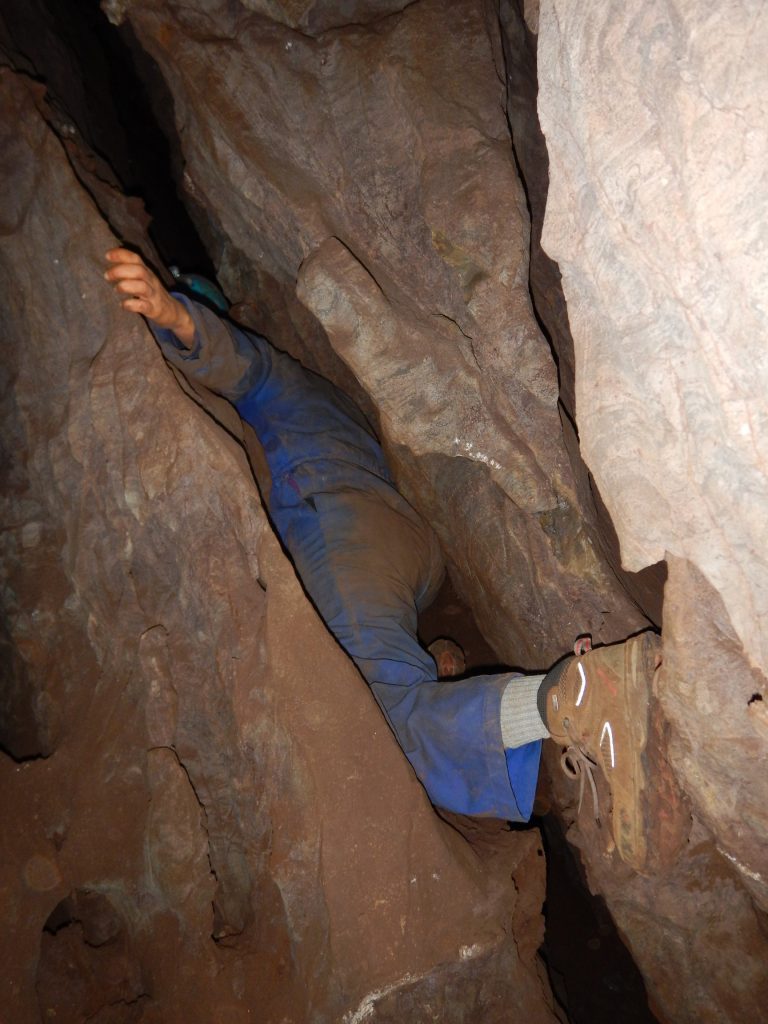

Look at the palm of your hand and spread your fingers wide. Now imagine squeezing your body through a gap narrower than the distance between the tip of your thumb and the tip your pinkie finger. Let’s make this a bit worse: the gap is in complete darkness, its walls are rough stone, and all you have is a tiny headlamp. Ok, now that you are there, all you have to do is carefully find and recover dime-sized fragments of an invaluable treasure.

That’s how researchers recovered the first Homo naledi child’s skull ever to be found.

The finding was revealed this week in two papers published in the journal PaleoAnthropology by an international team of 21 researchers.

Homo naledi are possibly our most mysterious long-lost cousins. They are an ancient human relative that lived in what is now South Africa, approximately 350 to 250 thousand years ago. They were first discovered in the Rising Star Cave system in 2013, in a research expedition led by Lee Berger, Professor and chair of Palaeo-Anthropology and Director of the Centre for Exploration of the Deep Human Journey at the University of Witwatersrand.

The research team, which includes Steven Churchill, professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke, named the child Leti (pronounced Let-e), after the Setswana word “letimela” meaning “the lost one”.

Leti was found in one of the previously unexplored narrow fissures that radiate from Rising Star’s known chambers. His resting site was a 15 cm wide and 80 cm long gap where only the smallest (and bravest) of explorers could fit.

Marina Elliot, lead author of the first paper and one of the explorers to first discover Homo naledi, said in a press conference that excavating Leti’s remains required explorers to wedge themselves practically upside down between two rock walls.

Finding yet another fossil in a prolific site may not seem groundbreaking, but finding a child’s skull is a major achievement. First of all, children’s bones are thin and fragile, and rarely withstand the test of time.

Second, finding a child’s skull gives researchers a precious glimpse into the development of Homo naledi.

“A child’s skull allows us to study how Homo naledi grew and developed, and how their growth rate and schedule compares to other hominid species, and to our own,” Churchill said.

In addition to skull fragments, researchers also recovered two worn baby teeth and four unworn adult teeth that were yet to erupt. These findings show that Leti would have been between four and six years old at the time of her or his death.

Based on similarities between the soil of the fissure where Leti was found and the better-known areas of the cave, Tebogo Makhubela, senior lecturer of Geology at the University of Johannesburg and author of the papers, estimated that Leti has been hidden in Rising Star for over 250,000years.

The discovery of Leti’s skull also deepens the mystery of how Homo naledi’s remains ended up in such a deep, dark, and treacherous cave.

Berger’s team had previously hypothesized that the first 15 Homo naledi individuals found in Rising Star had been disposed there by their own species, as a burial. This hypothesis created an uproar: could a small-brained hominin from over 300,000years ago bury their dead, just like we do?

Leti’s skull was found on a small shelf at the back of the cave’s fissure. No other bones were found, suggesting that Leti’s head may have been deliberately placed there. Leti, as well as all other Homo naledi fossils ever found, showed no evidence of being dragged by predators, carried by water, or tumbled around in any other way.

“Those were social individuals. Seeing one of their own being picked apart by animals could have been very distressing,” Churchill said. “Purposeful disposal of their bodies still seems like the most likely explanation.”

Berger is undeterred by nay-sayers. “This is science,” Berger said at a press conference. “We will continue testing and challenging our hypotheses with every piece of data that we get.”

The researchers hope that other teams around the world will study Leti and other Homo naledi fossils. To that end, Leti’s skull was CT-scanned, and its scans can be downloaded from Morphosource, an open access repository of museum specimens’ 3D scans hosted at Duke University.

Leti will probably not be the last treasure to come out of Rising Star’s spider web of narrow passages.

“I can’t wait to go back to South Africa and see what else is waiting for us in that cave,” said Juliet Brophy, Professor of Geography and Anthropology at Louisiana State University and lead author of the paper describing Leti’s skull.

“This finding makes us remember that exploration is always worth doing,” said Elliot, who is a researcher at Simon Fraser University and Witwatersrand University. “There is a lot still out there to be found”.

Elliot et al. was funded by the National Geographic Society, the Lyda Hill Foundation, the South African National Research Foundation, and the Gauteng Provincial Government, for funding the discovery, recovery and ongoing analyses of the material. Additional support was provided by ARC (DP140104282).

Brophy et al. was funded by the National Geographic Society, the Lyda Hill Foundation, the South African National Research Foundation, the South African Centre for Excellence in Palaeosciences, The University of the Witwatersrand, the Vilas Trust, the Fulbright Scholar Program, Louisiana State University, North Carolina State University, the Texas A&M University College of Liberal Arts Seed Grant program and the Texas A&M College of Liberal Arts Cornerstone Faculty Fellowship.

Citations:

“Expanded Explorations of the Dinaledi Subsystem, Rising Star Cave System, South Africa.” Marina C. Elliot,Tebogo V. Makhubela, Juliet K. Brophy, Steven E. Churchill, Becca Peixoto, Elen M. Feuerriegel, Hannah Morris, Rick Hunter, Steven Tucker, Dirk Van Rooyen, Maropeng Ramalepa, Mathabela Tsikoane,Ashley Kruger, Carl Spander, Jan Kramers, Eric Roberts, Paul H.G.M. Dirks,John Hawks,Lee R. Berger. PaleoAnthropology, November 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.48738/2021.iss1.68.

“Immature Hominin Craniodental Remains From a New Localityin the Rising Star Cave System, South Africa.” Juliet K. Brophy, Marina C. Elliot, Darryl J. De Ruiter, Debra R. Bolter, Steven E. Churchill, Christopher S. Walker, John Hawks, Lee Berger. PaleoAnthropology, November 2021, DOI: https://doi.org/10.48738/2021.iss1.64.