If you walked across Duke’s Engineering Quad between 9AM on Saturday, October 23rd, and 5PM on Sunday, October 24th, the scene might’ve looked like that of any other day: students gathered in small groups, working diligently.

But then you’d see the giant banner and realize something special was afoot. These students were participating in HackDuke’s “Code for Good,” one of the most eminent social good hackathons in the country.

Participants have to “build something, not just an idea,” said Anita Li, co-director of HackDuke. Working in teams, students develop software, hardware, or quantum solutions to problems in one of four tracks: inequality, health, education, and energy and environment.

Participants can win “track prizes,” where $2,400 in total donations are made in winners’ names ($300 for first, $200 for second, $100 for third) to charities doing work in that track. There are other prizes too. Sponsors, including Capital One, Accenture, and Microsoft give incentives: if participants incorporate their technology or use their database, they’re qualified to win that sponsor’s prize (gift cards, usually, or software worth hundreds of dollars).

This year, Duke’s department of Student Affairs sponsored the health track, in hopes that participants might come up with ideas that could help promote student wellness here at Duke. “It’s a great space for thinking about these issues,” Li said.

Li told me they had more than 1,000 registrations, though there’s always a little less turnout. HackDuke is open to all students and recent graduates, so that “you get to see these cool ideas from everywhere.”

Just under half of this year’s participants were from Duke, almost 10% hailed from UNC, and the rest were from other universities across the US and the world. 30 percent of participants were women — a significant increase from the last HackDuke covered by the Research Blog, in 2014.

This year is “particularly interesting,” Li said, because of the hybrid model. Last year, everything was virtual. This year, about 300 (vaccinated) students attended in person, making HackDuke one of the few Major League Hacking events with an in-person component this year. With the hybrid model, talks, workshops, and demos are all livestreamed so that no one misses out.

Some social events also had online elements: you could zoom into the Bob Ross painting session as well as the open mic, which Li said quickly turned into karaoke night. The spicy ramen challenge was “a little harder over Zoom.”

I came across Sydney Wang and Ray Lennon, along with teammate Jean Rabideau, as they were building a web app called JamJar for the Education Track contest. In the app, students give real-time feedback to teachers about how well they’re understanding the material. There are three categories: engagement (you can rank your engagement along a scale from “mentally I’m in outer space” to “locked in), understanding (“where am I?” to “crystal clear”), and speed (“a glacial pace” to “TOO FAST!”). Student responses get compiled and graphed to show mean markers of understanding over time.

Lennon said he’s participating because “this is the best way to learn: to be thrown in the fire and have to learn as you go.” Wang felt the same way. She’s new to coding, and feels like she’s learning a lot from Lennon.

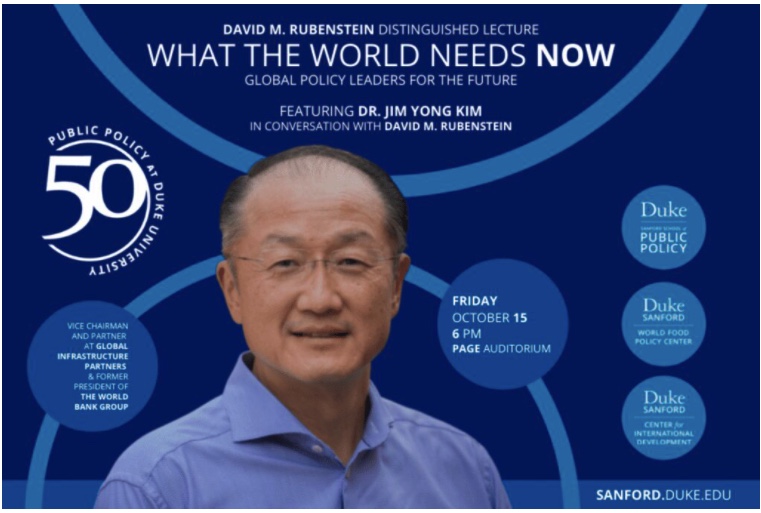

Like Lennon and Wang, many participants see HackDuke as an opportunity to learn. There are technical workshops where participants can learn HTML and CSS. There are talks where speakers discuss working in the coding and social good sector. The CTO of change.org, Elaine Zhou, flew to Durham to speak to participants about her experience. So there’s a networking opportunity, too — participants can meet people like Zhou doing the work they want to do, and professors and company representatives who can help them on their journey to get there.

There were challenges. Staying hydrated was one: by Sunday morning, they’d gone through seven cases of water, 16 cases of soda, and three cases of red bull. “It takes a lot of liquids,” Li said. And then there’s sleep — or lack thereof. When Li was participating in her freshman year, she slept for about three hours. Many people pull all-nighters, but “nap sporadically everywhere,” Li said. “It’s like finals season, with everyone knocked out.” She saw a handful of guys sleeping on the floor in Fitzpatrick. She gave them bed pads.

Li’s love for HackDuke is contagious. She loves to see participants focusing on social good and drawing on their awareness of what’s happening in the world. “People are thinking about things that are intense; they’re really worrying about issues facing certain communities,” Li said.

At HackDuke, people really are coding for good.

Post by Zella Hanson