This is the first of eight blog posts written by undergraduates in PSY102: Introduction to Cognitive Psychology, Summer Term I 2019.

We’ve all accepted a lie that we’ve heard before. For example, “vitamin C prevents the common cold” is a statement that rings true for many people. However, there is only circumstantial evidence supporting this claim, and instead, many researchers agree that the evidence in fact reveals that vitamin C has no effect on the common cold.

So why do we end up believing things that are not true? One reason is known as the “illusory truth effect” which claims that the more “fluent” a statement is or feels, the more likely it is to be remembered as true.

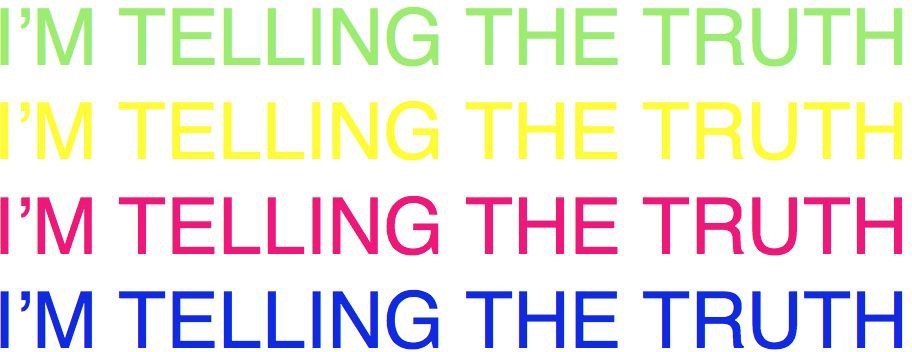

Fluency in this case refers to how easily we can later recall information. Fluency can increase in a variety of ways; it could be due to the size of the text in which the fact was presented, or how many times you have heard the statement. Fluency can even be influenced by the color of the text that we read. As an example, if we were only presented with the blue-text version of the four statements shown in the picture above, it would be easier for us to remember — compared to if we were only shown the yellow-text version — and thus easier for us to recall later. Similarly, if the text was larger, or the statements were repeated more frequently, it would be easier for us to recall the information.

This fluency can be useful if we are constantly told accurate facts. However, in our current day and age, truth and lies can become muddled, and if we end up hearing more lies than truths, this illusory truth effect can take over, and we soon begin to accept these falsehoods.

Vanderbilt University psychologist Lisa Fazio studied this during graduate school at Duke. Her aim was to explore this illusory truth effect.

Eighty Duke undergraduates participated in her studies. For the first part, participants were shown factual statements — both true and false — and asked to rate how interesting they were.

For the second part, participants were shown statements — some of which came from the first part of the study — and told that some would be true and some false. They were then asked to rate how truthful the statements were, on a scale from one to six, with one being definitely false, and six being definitely true.

Fazio and her colleagues found that the illusory truth effect is not only a powerful mental mechanism, but that it is so powerful, it can override our personal knowledge.

For example, if presented with the question “what is the name of the skirt that Scottish people sometimes wear?” most people would correctly respond with “a kilt.” However, if you were shown the false statement “a sari is the skirt worn by Scottish people,” you would be more likely to later report this statement as being truthful, even though you knew the correct answer before reading that false statement.

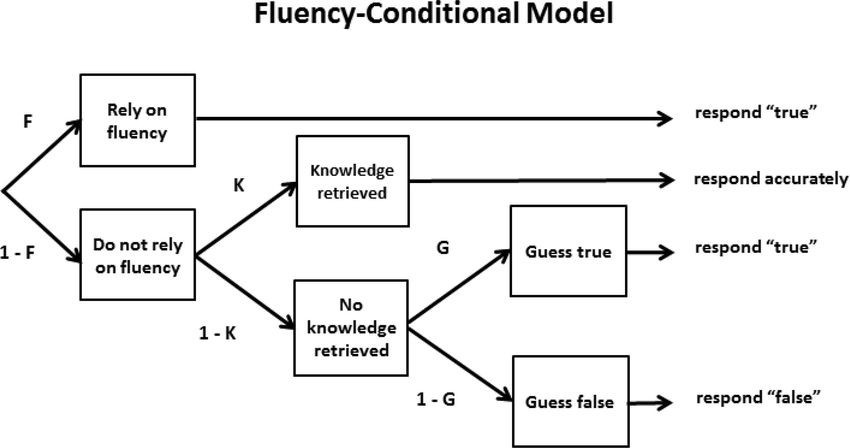

Fazio’s paper also proposed a model for how fluency and knowledge may interact in this situation. Their model (shown below) suggests that fluency is the main deciding factor on the decisions that we make. If we cannot easily remember an answer, then we rely on our prior knowledge, and finally, if our knowledge fails, then we resort to a guess. This model makes an important distinction from their other model and the underlying hypothesis, which both suggest that knowledge comes first, and thus could override the illusory truth effect.

All of this research can seem scary at first glance. In a world where “fake news” is on the rise, and where we are surrounded by ads and propaganda, how can we make sure that the information we believe to be true is actually true? While the paper does not fully explore the

effectiveness of different ways to train our brains to weaken the illusory truth effect, the authors do offer some suggestions.

The first is to place yourself in situations where you are going to rely more on your knowledge. Instead of being a passive consumer of information, actively fact-check the information you find. Similar to a reporter chasing down a story, someone who actively thinks about the things they hear is not as likely to fall victim to this effect.

The second suggestion is to train oneself. Providing training with trial-by-trial feedback in a situation similar to this study could help people understand where their gut reactions fall short, and when to avoid using them. The most important point to remember is that the illusory truth effect is not inherently bad. Instead, it can act as a useful tool to reduce mental work throughout one’s day. If ten people say one thing, and one person says another, many times, then ten will be right, and the one will be wrong. The real skill is learning when to trust the wisdom of the crowds, and when to reject it.

Guest Post by Kevyn Smith, a third-year undergraduate majoring in Electrical and Computer Engineering and Computer Science, and minoring in Psychology.

Guest Post by Kevyn Smith, a third-year undergraduate majoring in Electrical and Computer Engineering and Computer Science, and minoring in Psychology.