“I started thinking about how I might be different, how my life might be different, how my conversations might be different, if [‘To Kill a Mockingbird’] had not been a book that I was able to read in the 8th grade… to keep reading and reading again,” recounted Professor Kisha Daniels in her opening remarks of last month’s “Policing Pages” panel.

What truly is more formative in the awkward, acned stretch of middle school than Lip-Smackered gossip and English class? Yellow page paperbacks, palimpsests of doodles and students from years past. Purchased on teacher budget scraps and booster club wrapping paper sales, Shakespeare, Orwell, a hundred used copies of “Tuck Everlasting”: stained, dog-eared, and coverless.

Psychology and neuroscience researchers agree that reading (and, thus, books like “To Kill a Mockingbird”) weaves tapestries of yarny neurons and synapses, beneficial for the development of social-emotional skills, empathy, and creativity during childhood and adolescence.

Yet, America has recently witnessed persistent efforts to ban certain titles from K12 schools. In 2004 and 2005, for example, Stanford Middle (here in Durham) challenged the inclusion of “To Kill a Mockingbird” in its own library, citing the novel’s use of racial slurs.

It ultimately was not removed from the shelves, but the book remains one of the most challenged/banned titles in U.S. school history.

In 2021, the American Library Association reported an unprecedented 729 book challenges. So why, Daniels prompted, are we seeing such a high number of banned books? And why now?

Before answering this, Professor Sarah Ludington clarified some of the misleading rhetoric propagated by the popular media. “’Banned books’ is more of a slogan,” she explained. More accurate is the idea of challenging a book, whether in a library or on the class curriculum. This does not necessarily mean the book will be outright banned or even removed from the shelf or, if it is banned, permanently. In fact, books can be reinstated, even after their removal, back to their shelf and the occasional dust bunny.

In North Carolina, such a statute exists in state law that bars an individual, like a single librarian, teacher, or parent, from undemocratically removing or banning a book. Instead, local administrative boards must take a vote.

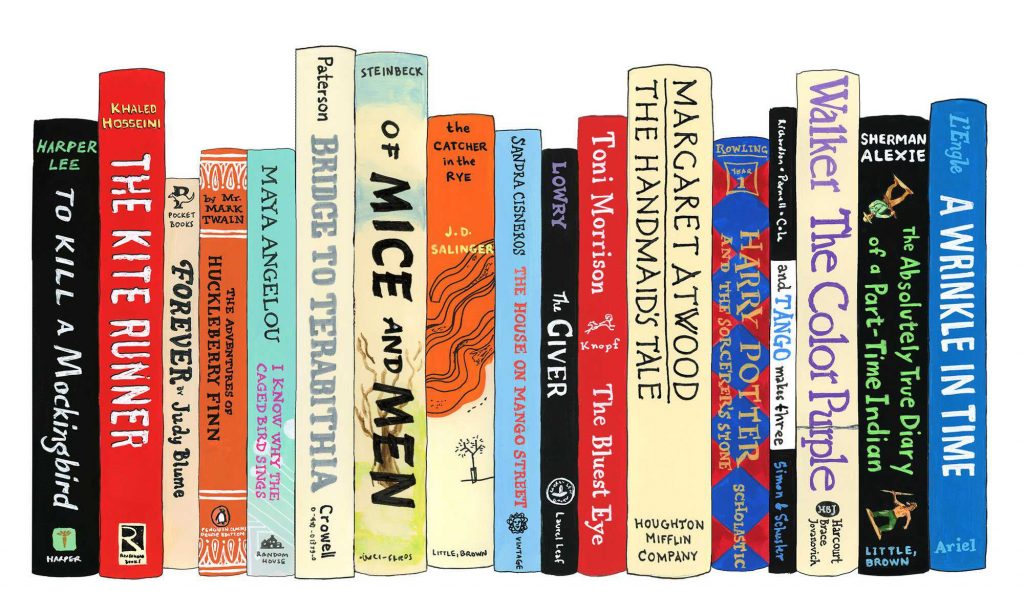

Illustration by: Jane Mount

University Librarian Joseph Salem argued that social media platforms, like Facebook, and online groups, like Moms for Liberty, create tectonic shocks that trigger tidal waves of book challenges. They’re echo chambers: amplifying calls to remove specific books from school libraries, ping-ponging literary “hit-lists” through cyberspace with titles such as: “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood, “Of Mice and Men” by John Steinbeck, “The Kite Runner” by Khaled Hosseini, and “Beloved” by Toni Morrison (you can take a look at the full list here).

These books disproportionately feature marginalized voices and are often “charged and sentenced” for containing “LGBTQ content, profanity, and/or sexual references.”

As we’re all aware, what once was local news can quickly leach into national discourse. A book ban in a rural Ohio county, for example, can be picked up by the local media, trend on Twitter, disseminate through Facebook until someone, say, in Texas or Arkansas or North Carolina decides they too want to challenge said book in their own school district.

This book-banning rhetoric and its implications are present elsewhere in education-related conversations. Take, for example, Florida’s dubbed “Don’t Say Gay” bill. In March, lawmakers in the Sunshine State argued that merely mentioning sexual orientation/gender identity in primary school settings is grounds for a lawsuit on the basis that such content is innately “sexually explicit,” no matter its context.

However, challenging certain books and even passing certain laws are usually not intentionally malicious acts. It is indisputable that some books simply do not belong on school bookshelves. A medical textbook, Ludington analogized, wouldn’t make sense in a library for children just learning how to read. But, in a high school with a more mature student body, its inclusion wouldn’t bat an eye. Further, in the U.S. more generally, First Amendment rights do not extend to all forms of speech anyways, including but not limited to “obscenity, child pornography, fighting words, and the advocacy of imminent lawless action.”

And though societal concern over the well-being of children is well-intentioned, it can often be misguided or out-of-proportion.

I don’t think it’s too outrageous to consider children as sentient and receptive, whether to new ideas, new perspectives, and/or new people.

Still, in the United States, a number of moral panics, concerning everything from poisoned Halloween candy to “Dungeons & Dragons” to subliminal messaging in rock music to Tide Pods, have been cause for parental concern.

In 1985, for example, Tipper Gore bought Prince’s “Purple Rain” album for her 11-year-old daughter and was shocked by its age-inappropriate lyrics. She took her concern to the Senate in a series of Congressional hearings which, though largely mocked, called for a music rating system like the kind adopted by Hollywood for movies.

Dee Snider, Frank Zappa, and John Denver somehow managed to assemble into the eclectic “primary counsel” for the musical defense and eloquently argued that labeling and banning albums is akin to censorship.

Gore’s campaign was ultimately unsuccessful.

But, it’s not difficult to see how censorship concerns voiced in the Senate in the 80s mirror the ones voiced today.

Ludington, a self-proclaimed First Amendment enthusiast, added that “…inherent in our idea of freedom of speech is this notion that truth emerges from robust dialogue… The best way to counteract whatever pernicious effect there might be, say from a book that you wanted to ban, is actually to read the book and reason against it.”

This kind of civil discourse is an idealism baked into the “apple pie” of American democracy. Quite arguably the Golden Delicious themselves. Over the course of U.S. history, there have been just and unjust efforts to suppress individuals’ freedom of speech. Take the infamous “yelling FIRE in a crowded theater” anecdote.

Experts concur, however, that most censorship is unproductive and often does little to actually stymie the ideas it so desperately wants to quash. In fact, as Daniels pointed out, banning books from school libraries typically does not decrease their readership and can actually drive their sales up.

But the implications of book banning run deep, implying that, as a society, there is little value in responsibly harboring and learning from certain (and often difficult) materials.

Salem described a collection on hate groups, gathered by the Southern Poverty Law Center and possessed by the Duke University library. He said, “If we take a step back for a moment and think that everything in the Duke University library… is something we endorse without understanding the complexity of why we might have it, either to learn from it as a good or bad example… one might say that owning or stewarding means that we support what’s in that collection. I would push back on that vehemently. It doesn’t comport with our values at all.”

After book banning efforts in school libraries reached an all time high in 2021, 2022 is trending to exceed last year’s figure.

Instead of arguing with disgruntled parents and Facebook groups, many underpaid librarians and teachers, Salem described, choose to self-censor, quietly removing contentious titles from their shelves to avoid unfair accusations lobbied at them in heated PTO meetings, over angry phone calls, or during school board votes.

To oppose this form of censorship, Daniels, Ludington, and Salem agreed: Read the books! Parents, Facebook group members, and legislatures alike, read before challenging, before banning, and then after banning. Reading is really the preeminent way to avoid unnecessarily suppressing free speech in schools; to introduce yourself to new ideas, to new discourse, and to new perspectives. Daniels put it best, “The book is innocent until proven guilty.”

Give it a fair trial.

In Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Atticus describes empathy to Scout in a way which resonates with many of the “Policing Pages” talking points, saying: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view… until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

If interested in the “Policing Pages: The American Classics” discussion, click here to watch.

If interested in resources on book banning, check out the American Library Association for more information.