By Nonie Arora

You may have been wondering who the student dressed as a lemur was for the Duke-Carolina game. Meet Joel Bray, lemur enthusiast and Trinity Junior.

Joel works in Brian Hare’s cognitive psychology lab where he does research on the psychology and evolution of nonhuman primates.

“Primates are an amazing way to understand human behavior, and specifically cognition,” Bray says. He studies lemurs at the Duke Lemur Center, which is home to the largest population of lemurs outside of Madagascar. Lemurs, most similar to the last common ancestor of all primates, are interesting because all 100 species are closely related at the genetic level, but they live in very different social and ecological environments.

In his first project, Joel studied inhibitory control in lemurs to understand how cognition evolves. This was part of a larger effort under NESCent, the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center. The project sought to compare dozens of species, including primates, birds, and rodents, on the same tasks using the same methods.

Joel tested the lemur’s inhibitory control by presenting them with an opaque cylinder with openings on both ends and food inside. The animals first learned how to retrieve the food. Then, the opaque tube was replaced with a transparent one. The impulse is to reach directly for the food item through the obstructed barrier, but to successfully retrieve the food the lemurs had to inhibit that response and reach from the side. Inhibitory control is considered to be important in both social and foraging contexts, and certain environments are expected to exert more selective pressure for the ability. In human children, it is predictive of future academic and social success.

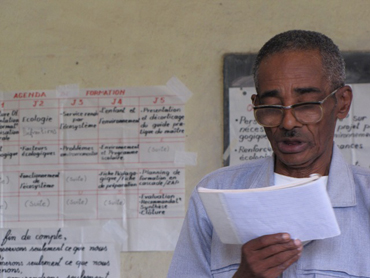

Joel, out of costume, studies a troop of ringtailed lemurs because he's a method actor. (Courtesy of Joel Bray)

More recently, Joel has investigated social cognition, specifically asking what lemurs understand about the perception of other individuals. Humans display “theory of mind,” the notion that other individuals have perceptions, knowledge, and beliefs different from one’s own. While lemurs are unlikely to have a complex understanding of the minds of other individuals, they may display more basic abilities.

In his current project, Joel is asking whether lemurs will take advantage of information about a human competitor’s visual perspective to acquire food. One food item is visible to the experimenter and the other is not, and the lemur must decide which to approach. It is expected that that species in large or complex social groups will perform better because their evolutionary history has selected for being able to understand what other individuals can perceive (i.e. “social intelligence”).

Ultimately, this research may lead to a better understanding of human cognition and whether our “big brains” evolved because of complex social environments.